Mr Daniel K. Kalinaki

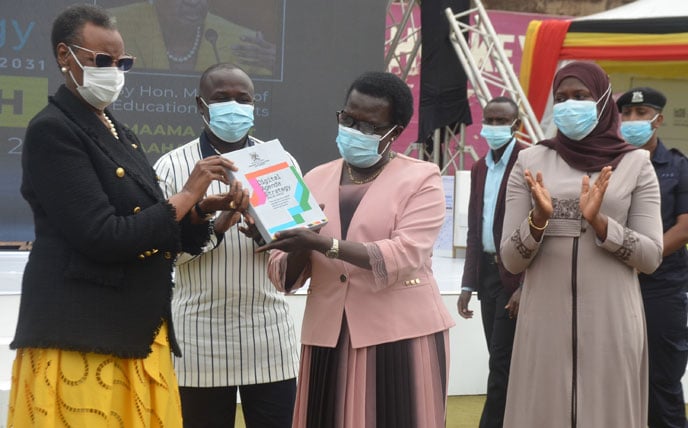

The recent announcement by the Ministry of Education that it will soon allow learners to bring digital devices to school and into the classroom has been welcomed by many as a sign of progress and modernising.

“The world is going digital,” many quip, so it makes sense to get children onboard as soon as possible, right? To any autodidact, the internet provides a sea of knowledge in which one can immerse oneself, expand mental horizons and learn new skills. It does not make sense for a child to carry a rucksack full of textbooks when they can have a tablet with digital versions.

However, there are many ways this policy shift could harm children and education outcomes. Start with regulation. Officials say the shift is aligned with other national ICT policies that seek to increase access to digital services and the internet, but it is not clear if sufficient public consultation has been done – at least among parents and teachers. As a result, questions remain, for instance about whether any device can be brought in, or whether they must be standardised for all learners.

This inevitably raises additional questions about cost, access, and content. Children in urban areas tend to come from homes with higher incomes than their rural counterparts. They are more likely to be able to afford digital devices or attend schools that have access to the internet and electricity. Unless there is a means-tested effort to make subsidised gadgets available to learners in rural areas – even if they are shared across students and classes – the digital chasm between rural and urban, rich and poor, will only widen.

The point here is not to wait for the poorest pupil to be able to afford an iPad before they are rolled out; it is to ensure that the design of public policy considers the principles of equity and inclusiveness. What about content? Little has been said about what learners are expected to find when they bring their devices to the classroom. Presumably, the national curriculum has been digitized and pupils will be able to see pictures of the Canadian prairies rather than merely imagine them on hot, sleepy afternoons.

However, without standardising equipment, internet access, cyber security, and access portals, how will Teacher Phoebe upfront tell that Peace Twashemererwa Internet in the back is reading about Paul’s letters to the Corinthians and not discovering, sweaty-palmed, the depths of depravity to which humankind has plumbed the darker recesses of the internet?

Even if school internet networks blacklisted some of these dark alleys of the internet, the proposal could suffer from at least three other challenges. The first one is particular to us; many schools no longer provide a wholesome education to children. The thrill of being chased down the playground at break time is something many children, boxed into concrete bunkers all day long, will never experience. That is a point about space.

There is also a point to be made about interactions. The best teachers touch their pupils with more than just the syllabus. They reach into the young timid souls sent forth into school, find a kernel, feed it with the warmth of care, water it with the fountain of knowledge, and allow it to grow its stem, roots and branches.

Finding stuff on the internet is great, but we must not lose the pastoral care that teachers (and parents, primarily) give to children. Many pupils are already victims of iParenting, where stressed parents turn to digital devices to occupy them; school, for many, is the only place where they are seen.

This brings us to the last point, of screen time. There is ample evidence to show the corrosive effects of excessive screen time on children. It harms their linguistic, cognitive, and social-emotional growth, inter alia. Children who spend a lot of time staring at device screens often suffer from obesity, depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders.

Do not take my word for it. Walk into any meeting room or restaurant and see how many people are talking past each other or not at all, because their eyes are glued to their mobile phones. Even better, put your phone on the table in front of you and see how long you can go without reaching out to get a shot of dopamine from a social media notification.

Adults are already damaged by this screen addition. And countries that have gone down this road before are struggling to cut access to screen time or banning mobile phones at schools altogether. As we walk down the same path, our faces glued to our phones, we should try not to walk into generational lampposts. Unless we are careful, children who bring tablets to classrooms might turn into adults who need injections for their mental health challenges.