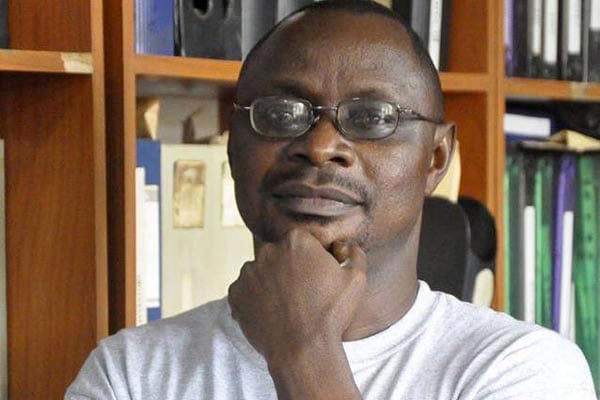

Mr Daniel K. Kalinaki

The decision to host parliamentary sessions in Gulu, northern Uganda, has been criticised in many quarters, primarily on account of cost. Part of the problem seems to be the price tag, rumoured to be as much as Shs20 billion for four regional sessions.

Part of it is just down to timing. The sessions follow months of unflattering public insights into Parliament and what many see as its profligacy. It also comes against the backdrop of the government’s refusal to pay for new medical graduates to undergo the mandatory internship they need to be certified as doctors.

Calls to spend the parliamentary money on the intern doctors, while well-meaning, underestimate the byzantine bureaucracy of public budgeting and overestimate the altruism of vote holders. Similarly, the defence offered for the sittings – that the money was already budgeted – wallows in shallow water and fails to read the room of public opinion.

Your columnist, eternally sanguine and inherently wired to look on the bright side, believes the regional sessions do not, in fact, go far enough. If the underlying idea is to take parliamentary business closer to the people, the majority of whom live in rural areas, why not go one step further and permanently relocate Parliament to Gulu?

Why celebrate the passing cloud of economic benefit for a few days when you can get rainfall all year round? Moving Parliament to Gulu or any of the other cities upcountry would trigger investments in real estate, hospitality, and a host of related sectors to serve the new footfall brought by parliamentarians.

Concentrating government offices and activities in Kampala has created a property asset bubble in the capital that is at odds with how congested and unliveable the city has become. The direct cost has been borne by Entebbe, which once was the seat of the government but now feels sleepy and abandoned. Less visible but no less painful is the opportunity cost paid by other towns and cities to which some of these entities and agencies could have been relocated.

As fate would have it, we have two very good examples of how the location of economic activity can affect the fortunes of an area and a region. The first is Jinja City, once the country’s industrial hub, which has been stymied by what one can only consider to be economic sabotage.

Jinja had it all. It lies next to the River Nile and the hydropower dams that supply most of our electricity. It has rail and road connections to the northern export route through Kenya and is also connected to the southern route through Tanzania via Lake Nalubaale. It also had supporting infrastructure in the form of warehouses, factories, accommodation, an airfield, tourist facilities, schools, etc.

Yet despite all that, we decided to cut down a forest reserve and drain the swamp in Namanve just outside Kampala to set up an industrial park. In doing so we added to the congestion in Kampala while draining the life out of Jinja and the wider peri-urban area in eastern Uganda that depended on it. Jinja did not have to die so that Kampala could live in eternal congestion.

Compare that with Hoima in western Uganda where oil and gas deposits – which thankfully for the people in the area can’t be relocated, say to Busega – have attracted infrastructure investments in the oil production and processing areas, a new international airport, roads, and a soon-to-be-built crude oil export pipeline.

These investments have created jobs and economic ecosystems in the Lake Mwitanzige area but they have not taken anything away from Kampala. Today you can buy a new land cruiser at a Toyota dealership in Buliisa, but you probably won’t find one in Jinja.

Kampala is, by default, the country’s economic hub but it need not be where we locate all public institutions. Why, for instance, does the Electoral Commission have to be located in the heart of the city? Why is the Ministry of Education and Sports building a skilling centre in a residential part of Kampala when most of the unskilled Ugandans are in the villages? Why does the Supreme Court have to overlook private residences in Kampala when it could have pride of place in, say, Masaka? Why do officials from the Dairy Development Organisation jostle for space with us in Kampala’s traffic when they could roam through the cattle corridor closer to their bovine clients? Why is the National Forestry Authority in Bugolobi and not in a clearing in Mabira forest? We could go on and on, but you get the drift.

In my view, therefore, the issue is not why parliament has to be shifted upcountry for a few weeks to take it closer to the people. It is why it has to return to Kampala at all.

Mr Daniel Kalinaki is a journalist and poor man’s freedom fighter.

[email protected]; @Kalinaki