Mr Muniini K. Mulera

Dear Tingasiga:

Last week’s rebellion in Kisoro District was a very welcome small step in Uganda’s struggle for freedom. After the allegedly rigged parliamentary primary election of the National Resistance Movement (NRM), in which the apparently more popular candidate was declared defeated, Abafumbira did the unthinkable. Led by Dr. Philemon Mateke, the district chairman of the NRM and a very loyal supporter of President Yoweri Museveni, the Bafumbira rejected the attempt to impose Rose Kabagyeni on them as their woman member of parliament.

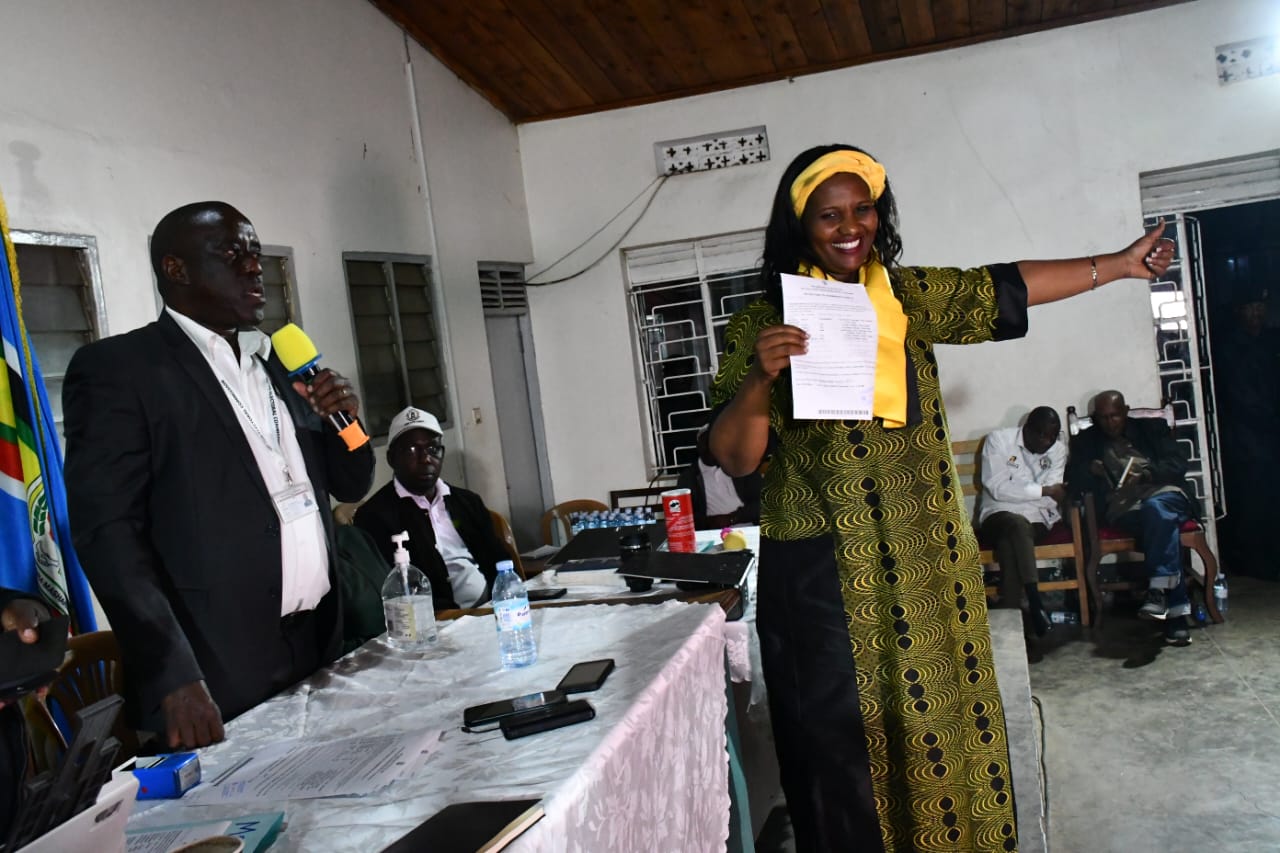

Unlike many aggrieved NRM candidates in other parts of Uganda who usually surrender to President Museveni’s “persuasion” to let the less popular candidates carry the party flag, Grace Akifeza Ngabirano, the candidate that had allegedly been robbed of her victory, joined forces with Mateke to push back against their party’s undemocratic mischief. They exposed the nakedness of the NRM and persuaded most Bafumbira voters to join them in their rebellion and support Akifeza’s independent candidacy.

For her part, Kabagyeni, the NRM candidate, mobilized party leaders from the national headquarters and other districts to lend a hand in the battle. Armed with hundreds of millions of shillings, the party operatives offered as much as Sh.50, 000 to 100,000 per vote. Some people accepted the bribes, but many declined them, a response that was as surprising as it was reassuring. The Bafumbira were rebelling against political abuse and manipulation that had long become the NRM’s standard operating procedure.

Whether President Museveni had sanctioned the cash-for-votes and the onslaught against Mateke’s rebellion remains unknown. However, nothing of consequence happens in the NRM without the president’s knowledge and approval. In the event, Museveni joined Kabagyeni’s ground forces two days before the election, confident that his power of persuasion and the Bafumbira’s traditional loyalty to him, would seal the deal for his party’s official candidate.

When the ballots were counted, Akifeza, the independent candidate, had convincingly defeated the NRM’s Kabagyeni, with a margin of 5,477 votes. The success of the Mateke-Akifeza rebellion was a striking change in a district that had been the president’s strongest base in southwestern Uganda for decades. The rebellion triggered memories of a dramatic event that I witnessed twenty-eight years ago.

On the evening of Friday April 19, 1996, presidential candidate Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, whose names had been re-arranged to Yoweri Museveni Kaguta, held a meeting with his campaign team in the Kabale District Council Hall. I was in the audience that night. Museveni opened the meeting by asking the leaders of his sub-county teams to share what issues irked the voters most and what the poverty and illiteracy situation was like in their areas.The first to report was a woman from Nyarusiza in Bufumbira (the traditional name of Kisoro District.)

“Ssebo purezidenti wacu, njewe ndashaka kukubwira ko iwacu Nyarusiza, ufite ijana ku ijana!” (Our President, I wish to inform you that you have one hundred percent support in Nyarusiza.) The lady sat down. After some deafening applause from the audience of about 200 people, a representative from another sub-county sang the same hymn to the President. And so it went, sub-county representative after representative, assuring Museveni that the election in Bufumbira was in the bag. Subcounty representatives from Kabale District, comprised of Ndorwa, Rubanda, and Rukiga counties, took up the song: “Ssebo purezidenta waitu, ninkuhamiza ngu owaitu Bufundi oyine igana ahari igana.”

The applause after each declaration was a temporary relief from the monotony of the stanzas that were merely the Rukiga version of the Kifumbira/Kinyarwanda lyrics. Not even one subcounty representative mentioned the issues that appeared to be on Museveni's mind.I felt very sorry for Museveni, not only because he was exhausted and could have done without this meeting, but because he was a ruler of a mute society. After recording the evening’s events in my journal, I ended with the question: “Is it any wonder that African leaders quickly believe the illusion of their god-like supremacy?”

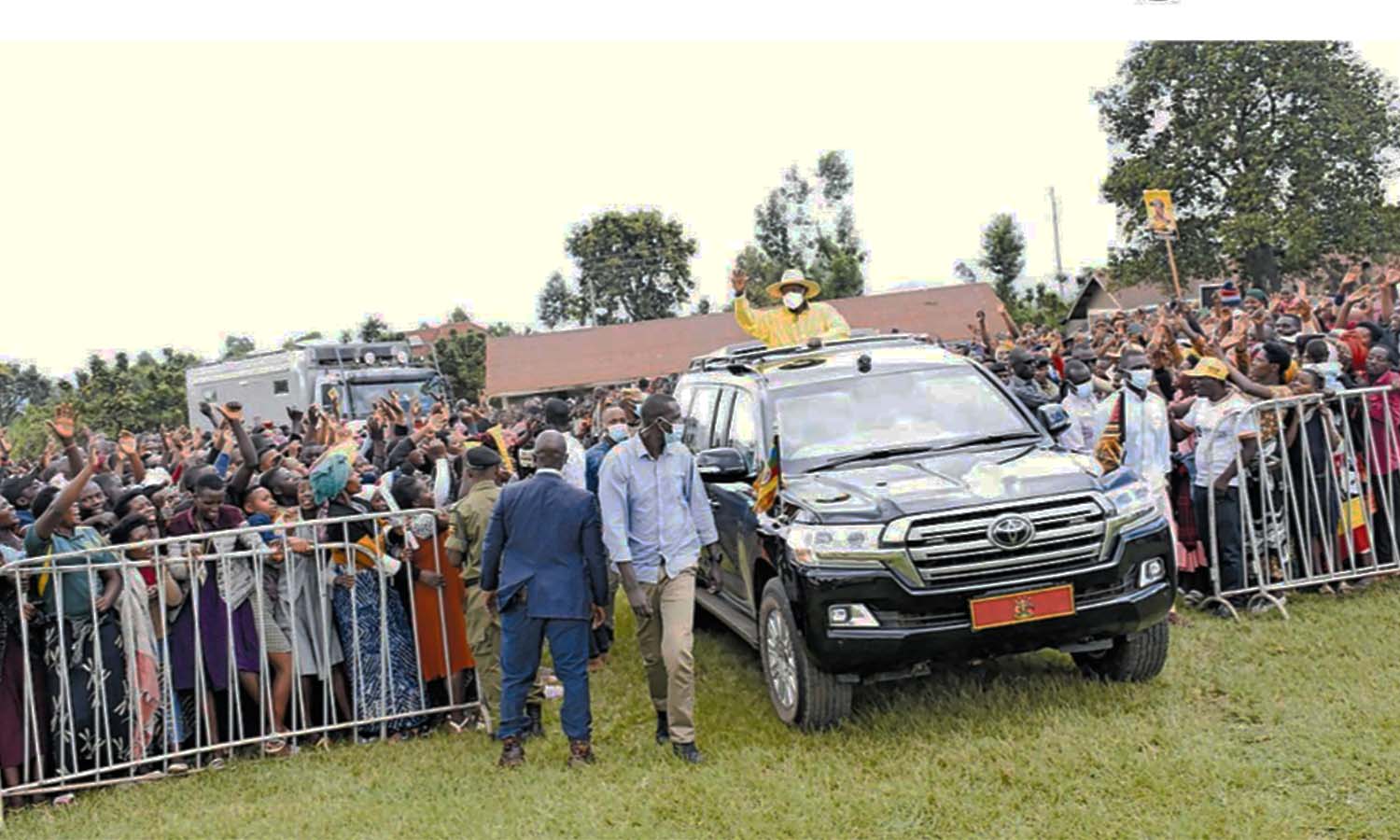

Two days after Museveni's landslide victory against Paul Kawanga Ssemogerere, my friend and I set off from Entebbe for Kampala at 6 p.m. My journal entry from that day reveals that I was behind the wheel of a borrowed, air-condition sedan, and the journey that usually took thirty minutes those days, took us over three hours. Huge crowds of branch-waving peasants had blocked the roads to celebrate the President's victory and to welcome visiting heads of state who were coming in to witness the start of Museveni II.

"No change! No change! Why change? No change!" sang the crowds of sweating malnourished peasants, many in rags that passed for clothing. To get through the throngs, I honked in unison with the chants of “no change”, to which the revellers responded with waves as they gave way to us. Without doubt many of these "no-changers!" had no access to clean water or reliable health care. They belonged to the desperate class, a level below the official poor class.

Considering the choice of candidates that Ugandans had had in the 1996 presidential vote, the "no-change" slogans were understandable. But one could not miss the irony of it all. Desperately poor people, burdened by disease, extreme poverty and an obscene national debt, wanting no change from the kleptocracy that had become depressingly obvious.

Perhaps this was democracy at work. But more likely this was a disconnect between the people’s lived experiences and the reality of their government that offered them empty promises that would soon acquire names like “prosperity for all”, “bona bagagawale”, and “parish development model”. Nearly thirty years later, Museveni is very unlikely to get the same ululating, branch-waving throngs along the Entebbe-Kampala highway or other throughfares in Buganda.

On the other hand, he is still guaranteed close to “ijana ku ijana” in Bufumbira, partly because of the influence of Dr. Mateke, a larger-than-life figure in his district, a man that enjoys enormous respect among Banyakigyezi, me included. Mateke is one of the few politicians from Kigyezi that are committed to uplifting their people. He has been a go-getter since his first foray into elective politics in 1980.

A former minister of state for education in the Obote II government, and a former minister in Museveni’s government, Mateke continues to leverage his power and popularity to bargain for community development projects. It was Mateke who forced President Museveni to implement an old promise to tarmac the Kabale-Kisoro Road, one of the very worst motorways during my childhood and youth. His successful rebellion last week has put Museveni on notice that Mateke remains the password for the president’s access to his “ijana ku ijana” support in Bufumbira.

The Mateke rebellion has offered NRM supporters elsewhere an opportunity to reconsider their own rights and push back against the party bosses, including the president. It is not easy, of course. Museveni’s is a military regime. However, Dr. Mateke has demonstrated that courageous and patriotic citizens can still put up peaceful resistance, even within a very constrained political space.