Mr Muniini K. Mulera

Dear Tingasiga:

Kenyans call their current president Zakayo, after Zacchaeus, the height-challenged tax collector at Jericho 2,000 years ago, who was reportedly very wealthy.

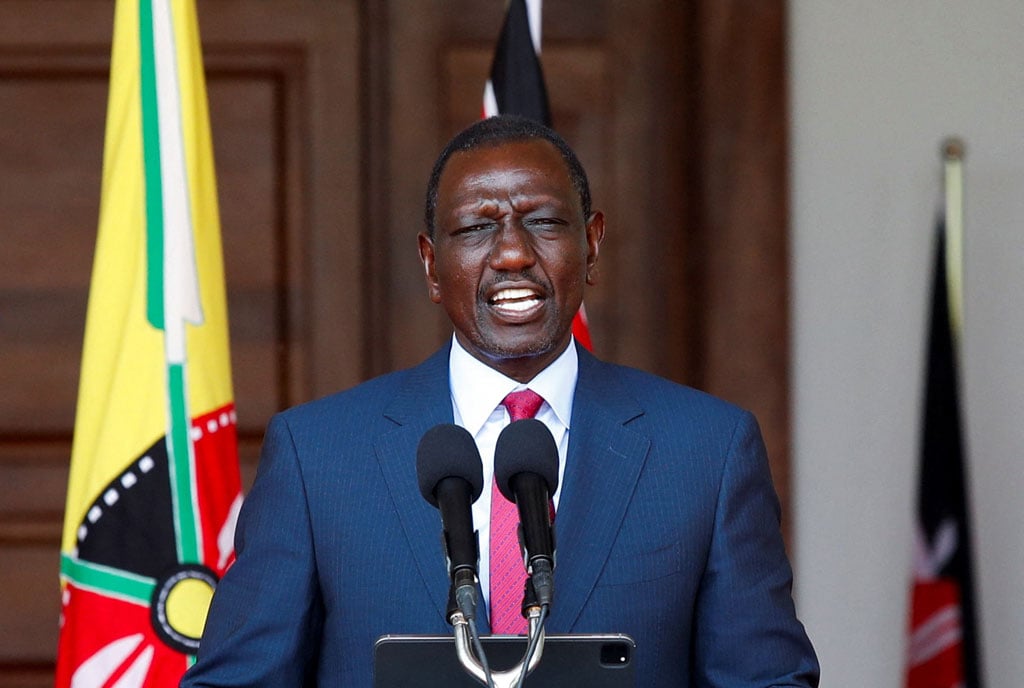

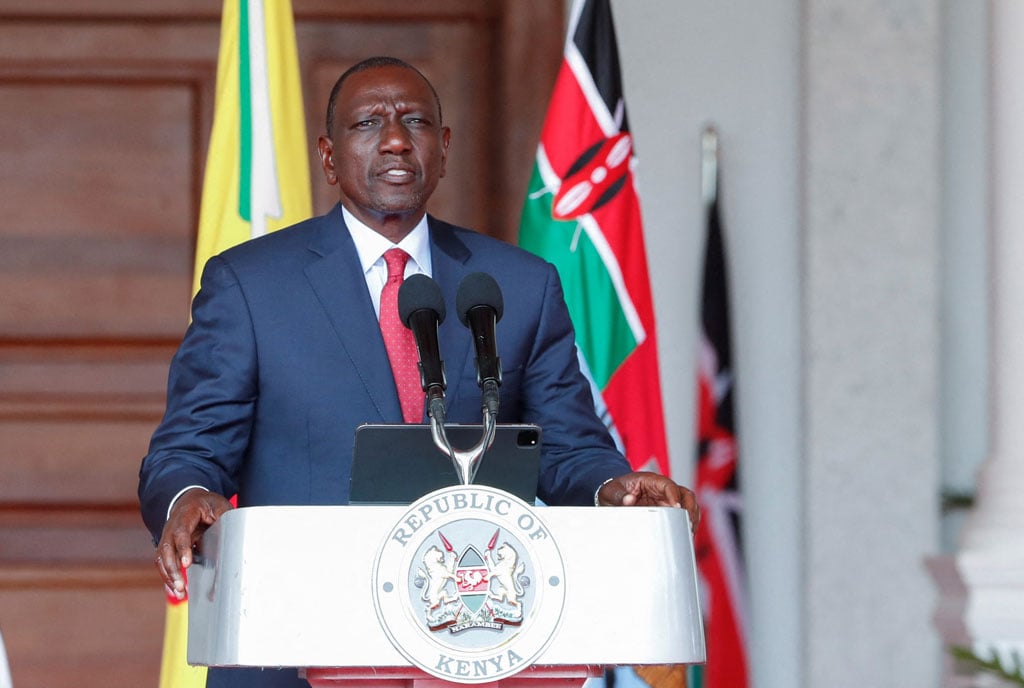

President William Samoei Ruto’s attempts to tax Kenyans even more, while he and other leaders in his government indulged in a sinfully extravagant display of wealth and luxury, rightly earned him the nickname. The Biblical Zakayo was intensely hated by the hard-working citizens of Jericho. The Kenyan Zakayo, became so intensely distrusted and disliked that, less than three years after becoming president, he came face to face with a widespread rebellion, led by an invisible force of young Kenyans. As I write, President Ruto is scrambling to appease Kenyans, playing catch up to people that he previously assumed were his subjects, and still unsure whether he will survive the next election.

Whereas the frustration of Kenyans towards their government is as old as that Republic itself, the immediate trigger of the current rebellion was President Ruto’s attempt to impose more taxes on them. Not that Kenyans do not want to pay taxes. Like most people in the world, Kenyans are simply infuriated by the extreme disconnect of their rulers from the realities of the majority. Kenyans have reached the breaking point because of socio-economic disparities that are caused by a parasitic minority, feeding off an increasingly malnourished majority.

Many Africans easily relate to the situation in Kenya. The parasitism in Kenya probably pales when compared to that in some African countries. Whereas public education and health care in Kenya remains well behind what it was 50 years ago, it is miles ahead of the situation in many countries. A large percentage of citizens are cut off from the much-publicized economic success stories of their countries, which supposedly benefitted from the structural adjustment policies imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

For example, every time I drive on the road from Muhanga to my home in Mparo, Rukiga District during the rainy season, the recurring question that flashes through my mind is: “Is this part of Uganda?” The same question arises when I see groups of unemployed young people, hanging out in sad-looking hamlets; school children heading to poorly resourced rural schools; pregnant women and sick people sitting at health centres that are severely under-resourced; piles of uncollected garbage near food markets; raw sewage draining past restaurants on its way to areas where children play; and so much else that shows total absence of government.

I invariably get flashes of the power, extravagant lifestyles, and living in the clouds that the ruling classes in Uganda and other African countries love to display before the Wretched of the Earth. When I see politicians’ motorcades, complete with sirens and armed police escorts, speeding along awful roads, splashing muddy water at women and children on their way home from their fields, I feel pain that is exacerbated by memories of friends and relatives that died in the various wars of “liberation” in the 1970s and 1980s. The road that passes near the home of David Kagoro Kangire, my childhood friend who was publicly executed 51 years ago because he had taken up arms on behalf of the Front for National Salvation (FRONASA), looks and feels like ekikoroogyero (a cattle path). I drove along that road on March 9 this year. The rain had created a most treacherous obstacle course that was a danger to pedestrians, motorcycles and four-wheeled motor vehicles. I could not but think of David Kangire, and remember our conversations about justice, fairness, and so much that exercised our very young brains. Did he die so that others may rule Uganda, and forget him and his people, as though they were mere tools in a struggle that was never about them?

Kangire’s neighbourhood has dozens of beautiful residential homes, owned by tax-paying men and women who serve Uganda in high-capacity jobs. I do not speak for them, of course, but I suspect that they too wonder why they pay taxes. Which causes me to ask again, in good faith and with patriotic intentions: What is the value of the government to most Ugandan citizens? Should Ugandans pay taxes without asking why they must do so? These are questions that are best answered by Ugandans living in Uganda, for they know best what their taxes are doing for them. What I can share with confidence is my experience here in Canada where I have paid taxes for more than forty years.

Canadians pay very high taxes. They do so without rioting or invading their provincial and federal parliaments. There are several factors that account for this peaceful compliance with this country’s taxes. The bottom line is that Canadians see the fruits of their labour, and enjoy public services of a high standard, accessible to all citizens regardless of social status. For example, the hospitals and doctors’ clinics where the prime minister and his ministers receive health care are the very ones where homeless and other socioeconomically struggling people go for care. The millionaire, the prime minister, and the struggling citizen pay the same – zero. Yes, zero. Healthcare in Canada is considered a human right, and a sacred trust that does not discriminate against anyone. I state this with certainty from firsthand experience.

This visible equal access to basic services, and the ordinary lifestyles and public conduct of most politicians, minimizes public anger towards the leaders, even as the taxes continue to rise. Which brings me back to William Ruto of Kenya. He can still redeem himself. Like his Biblical namesake, he can genuinely turn to the Lord, not through meaningless proclamations and displays of his Christian faith, but through true repentance and actions. We read in Luke 19:1-10 that when Jesus invited himself into Zakayo’s home, the latter said to Jesus: “Behold Lord, the half of my goods I give to the poor. And if I have defrauded anyone of anything, I restore it fourfold.” Jesus responded: “Today salvation has come to this house, since he also is a son of Abraham. For the Son of Man came to seek and to save the lost.”

Kenya’s politicians in Nairobi and the county capitals can complete the story of Zakayo, and humbly follow the path that transformed the ancient tax collector into a true follower of Jesus Christ.

Muniini K. Mulera is Ugandan-Canadian social and political observer.