An ode to the man whose name I carry

Benjamin Rukwengye

What you need to know:

- On the morning of 19 December, 2023, my grandfather, together with my brother Edgar, nephew Keine and their driver Kassim, perished in a nasty road accident in Kabwohe, Bushenyi district. To them!

Few things are as important as a name. It is, literally, who we are. Yet, it is possible to go through life without questioning why and how we came to carry the names that we do. In many African cultures, names carry meaning and weight. They convey the story of the times and the circumstances in which we came to be.

So, “What does Rukwengye mean?” I asked my grandfather, Muzeyi Eria Rukwengye, a few years ago, because I often get asked.

“My family used to have a plantation that was often attacked by birds called “Enkwengye”. To protect the crops, every member of the family took turns at chasing the birds away. On the day I was born, (September 29, 1928) it was my mum’s turn to keep watch and scare away the Enkwengye.”

Uganda’s population structure is such that just about 3 percent of our population are over 60. Without talking to them, we are without history. In 2021, we had an extended conversation. He was 93.

“What was your childhood like?” I probed.

We had lots of cattle and it was the responsibility of the boys to herd them. But the colonialists hated it. When the cows fell sick, they didn’t bother with treatment. They let them die and impoverished us. They also threatened to arrest my father if he didn’t send us to school. He let me and two of my brothers go to school.

What did you make of it?

They made us poor. When the colonialists came and killed our cattle and forced us to go to school, that meant that our fathers had nothing substantial to bequeath. Consequently, we also had no real wealth to give to your parents, apart from education. They will also not have much to leave you with. The Whites kept their cattle and land but also sent their children to school. But for us, they took away the wealth and left us with just their education.

Where did you go to school?

For primary, we used to walk from Mushunga, in Mitooma to Bweranyangyi, in Bushenyi. A very long walk of about 15 miles. You would return home so tired, sleep for about 3 hours and then start the journey back to school for the next day. It was very unsafe too. We were afraid of getting attacked by Leopards.

When I finished Primary school, I requested my father for transport, took a bus and went to Masaka. Two of my Primary school friends were at Kako Secondary School, so I followed them there. I did not have the school fees or admission, but I knew that school was the only way out. So, I went to the Head teacher and explained myself. He made me work for him for a year, gave me my first pair of shoes, and then enrolled me into school.”

So how do you become a teacher?

After Kako, I went to Bugema Adventist Secondary School and then qualified to join Teacher Training College in Nsambya. When I completed, I was posted to Kabarole where I taught and worked my way up to headmaster level. The school in Kazingo was in the mountains and hard to reach. You would walk for about 6 miles just to get there. To ease my movement, I bought a motorcycle. But the place is rainy and very cold, so I eventually decided to buy a car around 1958.

What was it like being a teacher?

I loved it but even then, the money wasn’t much. My family was growing bigger and my salary wouldn’t support us. I needed to explore other options so I decided to go into business and become a trader. Since I had not reached retirement age yet, I used a technicality in the contract to get early retirement. We then bought and built in Ishaka town, where I operated a shop until Amin’s war which forced us to close. On the day we left, I had 15 pairs of bedsheets, 23 blankets and lots of other merchandise in stock. We abandoned all of them.

There are a thousand ways to die. But if you are 95, a tragic road accident will probably not make the list - unless you are Ugandan. On the morning of 19 December, 2023, my grandfather, together with my brother Edgar, nephew Keine and their driver Kassim, perished in a nasty road accident in Kabwohe, Bushenyi district. To them!

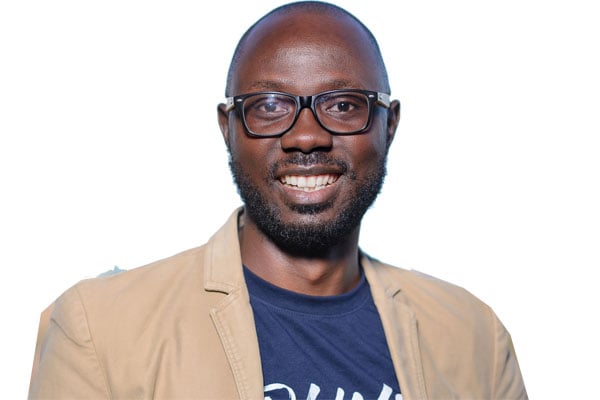

Mr Rukwengye is the founder, Boundless Minds. @Rukwengye