Prime

Is PDM the right medicine to cure biting rural poverty?

Author: Asuman Bisiika. PHOTO/FILE

What you need to know:

- As long as a programme involving socio-economic development puts the distribution of money at the centre, there is a likelihood of failure.

"The Parish Development Model (PDM) across a number of districts are at crossroads as some beneficiaries switch to other enterprises as opposed to those that qualified them to be enlisted for the programme,” a story from the Monitor reported.

As an online reader of the Monitor, I am not sure whether this story was given what I consider as appropriate space and page. My call for wider and deep media coverage of PDM is driven by the fact that it (PDM) is now the flagship programme for what Museveni calls “socio-economic transformation of the country”.

However, although resources have been pumped into PDM, there is a very conspicuous low public policy perception (and absorption) on the programme. In the first place, design of the programme was top-down driven. But we are talking about the public till. The media would therefore be at their best public-service-offering to give the programme the interest it deserves.

We have learnt that Mr Museveni is frustrated over the failure or limited absorption of PDM. Why this low policy absorption when funds and administrative structures are said to be in place? Why has the money not reached the bona fide beneficiaries?

***************

Whereas Ugandans are sure PDM may not solve their social and economic problems, it remains a very a good shot at the target. However, as with other programmes (before it) like Naads, Operation Wealth Creation (and others before them), the challenge has always been the issue of governance.

I am a regular visitor to rural communities and my visits give me testimony of a dire poverty. As I have said elsewhere, “the poverty in the countryside is annoyingly very disabling. Most of the able bodied youth strive to go to Kampala. There is a high sense of lacking hope. Lacking hope (being hopeless) is quite different from (and more challenging than) ‘attitude change’. One can only change his or her attitude when he or she is hopeful or sees an inspiring and relatable story that gives him or her some hope. It is wrong to ask poor people to change their attitude when they can’t fix two square meals a day; worse if you limit your job to just throwing money at them.”

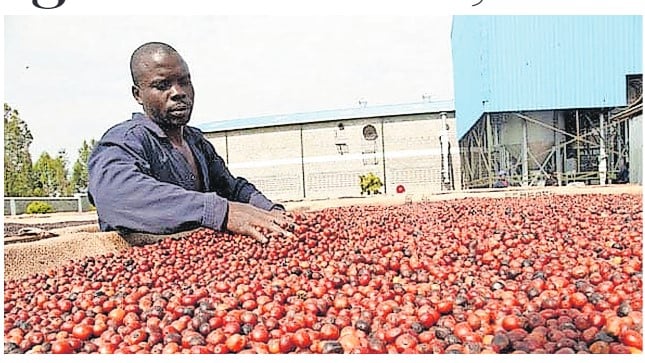

Up to 1990, the co-operatives were the central pillar of the social economic development of the people of Uganda. The construct of the co-operatives movement was simple: state architecture by policy, support system for production and marketing and production by co-operators. However, from 1990, the socio-economic development agenda has been centred on the provision of finance with very limited symbiotic contact with the state actors. Whereas there has been several government efforts to spur up the socio-economic development, the challenges faced by the rural farmers have never been addressed. There was Rural Farmers Scheme, Poverty Alleviation Programme, Poverty Eradication, Entandikwa (Start Up Fund?) to Prosperity for All, Naads, Operation Wealth Creation, Emyooga. And oh yes, now we have Parish Development Model. The objective of all these programmes has always been to enable subsistent rural farmers to produce more than their consumption needs and earn some money from the surplus.

But the government has just limited its job to pouring money into the hands of unprepared poor people. This can be very terrible when the choice of beneficiaries is based on know-who and the divisive political dynamics obtaining in the country.

As long as a programme involving socio-economic development puts the distribution of money at the centre, there is a likelihood of failure. The people’s effort and input must be the defining aspect of any programme.

Mr Bisiika is the executive editor of the East African Flagpost. [email protected]