Prime

Muteesa I killed more ‘martyrs’ than Mwanga

Rogers Magala

What you need to know:

- The Martyrs Day celebrations seem to negate what would be the salt of the Good News message; the repentance of Mwanga.

Buganda Kingdom has existed for more than 800 years since its creation in 1200 by Ssekabaka Kato Kintu. Kintu took over after killing Bemba Musota, who was a ruthless leader at the helm of all clans in ‘Ensi Muwawa’, which would later become Buganda Kingdom.

Since Kintu’s reign, Buganda has been ruled by 36 kings, most of whom enjoyed extreme authority until an Anglo-Buganda Treaty was signed in 1900. Ssekabaka Mwanga was the last King of Buganda to enjoy such maximum authority.

Much as Mwanga and his predecessors were not creators, they would give their subjects a chance to live or deprive them of their breath at a snap of their fingers and their death would be justified by custom.

During Ssekabaka Ssuuna II’s reign between 1826 and 1856, the first foreign religion (Islam) made its way into Buganda. However, it was not whole heartedly received by Muteesa I as it was by his father Ssuuna II. Muteesa passed a decree to his subjects to proceed with Islam classes but prohibited the circumcision of any of his subjects. The cultural norm in Buganda was that kings’ blood should not be shed; then what would Islam be when isolated from its canonical ritual of circumcision?

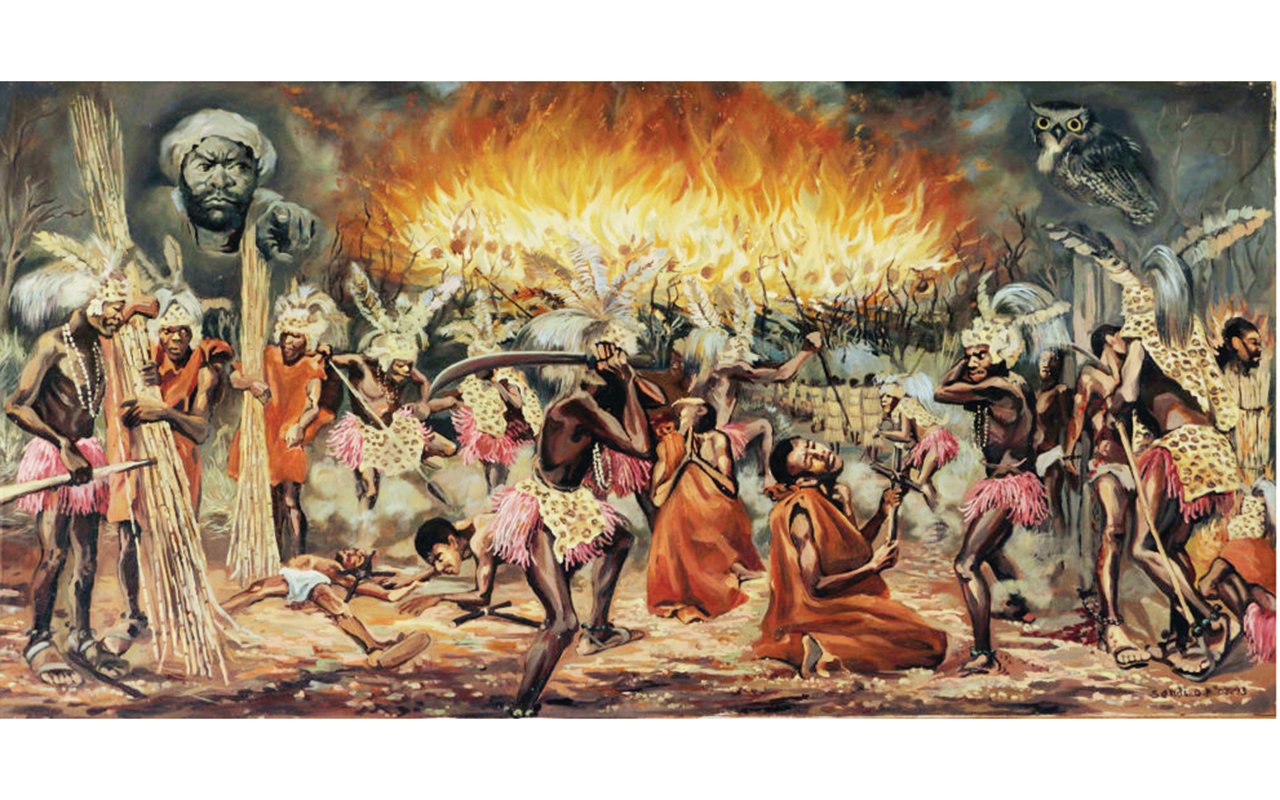

One day in 1876, Ssekabaka Muteesa I treated his people to a sumptuous feast, which a batch of Muslims resented because the meat was from animals slaughtered by non-muslims they referred to as bakafiri, (non-believers). He ordered their arrest and more than 70 Muslims were burnt at Namugongo.

Additionally, 27 Muslims were executed for being circumcised under the teachings of Islam. They were found guilty of disobeying the king’s orders against circumcision.

The death of Muteesa I in 1884 sparked a cold war among three religions; Islam, Catholics, and Anglicans. Each wanted to win the heart of Mwanga. At the time, Mwanga was only 18 years and was part of the young men taking Catholic theology classes. The Catholics were very happy because they believed Mwanga would make their religion official, unlike his father who never belonged to a particular religion at the point of his death.

It only took one year for Mwanga to send all Christians in his kingdom into a “coma” after he ordered the killing of Bishop James Hannington in 1885. This incident brought to reality all followers of Christianity and Islam that Mwanga was not ready to pay allegiance to any of their religions. He strived to protect the ultimate authority that lay on the throne of his ancestors

In the succeeding year on June 3, 1886, the killing of 45 Christian martyrs was the last straw that broke the camel’s back. Mwanga I’s dominance steadily faded until he was kicked off the throne on September 10, 1888. This was followed by the proclamation of 22 Catholic Martyrs of Uganda as Saints by Pope Paul VI on October 18, 1964, at St Peter’s Basilica, Rome.

However, after reclaiming the throne in 1890, Mwanga became a darling to his kingdom, parallel to the one who had killed the martyrs. He became a Christian and was baptised. It was Mwanga, at the request of Pere Simeon Lourdel, who was commonly known as Mapeera, who offered land that hosts the current Lubaga Cathedral to the Catholic Church.

The story of Ssekabaka Mwanga is not told in its entirety, which reduces him to a villain at the expense of a towering king who squeezed his century-old achievements into a 13-year-long reign at the age of 34 when he died.

The manmade lake in Ndeeba was created at the snap of his fingers. He was the first king to build a brick wall around the Mengo Palace.

Unfortunately, the Martyrs Day celebrations seem to negate what would be the salt of the Good News message; the repentance of Mwanga. Whenever the Good News about the Uganda Martyrs hails their faith in Christ and ignores the repentance of Mwanga, makes the message incomplete. Isn’t it time to reflect on this double-edged message about repentance and faith?

This article is inspired by Rev. Fr. J. L. Ddiba, in his book Eddiini Mu Uganda.

Rogers Magala, Law student at Uganda Christian University.