Prime

Sir, it was my son that killed your son

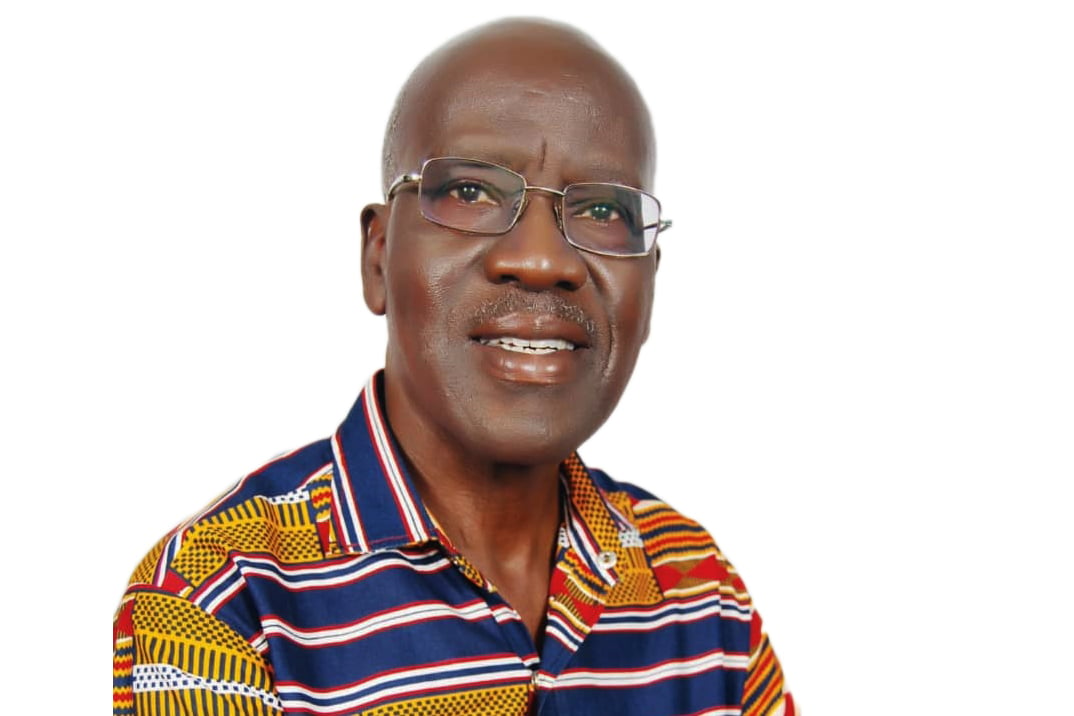

Prof Timothy Wangusa

What you need to know:

- Sixty-four years ago is, of course, 1959: only three years before Uganda attains her colourful ‘flag and paper independence’ from Britain her colonial master.

Esteemed and untiring perpetual explorer, please come fly with me to a point 64 years ago in Uganda’s past – and you will there re-live with me a supreme moment of intellectual, emotional, and moral experience that is at the same time absolutely unforgettable.

And that supreme moment is comprised of one heart-broken man painfully revealing to another heart-broken man – across the skin-colour bar-line – ‘It was my son that killed your son’.

Sixty-four years ago is, of course, 1959: only three years before Uganda attains her colourful ‘flag and paper independence’ from Britain her colonial master. And so here we are, you and I, at Nabumali High School, and reading books in Senior Two, in that fantastic atmosphere which I have elsewhere described as conducive to youthful ‘excitement of learning’.

Most remarkably, none of the history we have been taught so far is African; and none of the literature books we have read so far is African or by an African.

It is a fact that Amos Tutuola in 1952 authored Africa’s first novel in English by an African, and that is The Palm-wine Drinkard; and that Chinua Achebe in 1958 authored Things Fall Apart, Africa’s first classic novel in English by a black African – but these titles are yet to be made known to us.

And that is how it so happens that the first fiction story book based in Africa that we fall in love with is Cry, The Beloved Country by Alan Paton (1903-1988), first published 1948; Alan Paton being, our teacher informs us, as African deep down in his heart as any ‘settler’ White man can get to be.

On opening the book, it immediately hooks us by planting us on a beckoning ‘…lovely road that runs from Ixopo into the hills. These hills are grass-covered and rolling, and they are lovely beyond any singing of it….The grass is rich and matted, you cannot see the soil….Stand unshod upon it, for the ground is holy, being even as it came from the Creator…’

Wow, this cute South African scenic setting, captured in rippling lyrical prose, resonates so well with Mt Elgon and its foothills all around us with their still-virgin tree and grass cover – that we hardly bother whether or not the tale that follows is historical fact or fictive fantasy.

It is the tale of a country beloved by both its impoverished Black indigenous people and its White opulent ‘settler’ people; and, specifically, it is the tale of the elderly Rev Stephen Kumalo, who travels from his poor but culturally and spiritually rich rural parish to Johannesburg, initially in search of his only sister, and, additionally, his only brother, and his only son – who have been swallowed by the city, and have never returned to the village of Ndotsheni.

There, in the city, while looking for his sister, Rev Kumalo learns about the grave and tragic involvement of his son Absalom in the murder of a city engineer at his home in a burglary.

Coincidentally and ironically, the murdered Arthur Jarvis, who leaves behind him very conscientious writings about the need for social justice for the under-privileged Black population of South Africa, is the son of the wealthy farmer James Jarvis, whose farm lies next to the impoverished parish of Rev Kumalo back in the village; and where the two men have never met!

It is after the court has sentenced Absalom to be hanged for his crime that Rev Kumalo brokenly goes in search of James Jarvis while the two of them are still in Johannesburg.

And when the two do meet, we experience one of the most moving and most unforgettable scenes in all imaginative writings. Full of contrition and burdened with a sense of inter-racial evil – Kumalo reveals to Jarvis, ‘It was my son that killed your son’.

Prof Timothy Wangusa is a poet and novelist. [email protected]