Author: Moses Khisa. PHOTO/FILE

There has been so much talk about the Uganda Law Society (ULS) in recent weeks. A new president was elected late last month with so much pomp and triumphalism, to boot, at least going by the chattering and unmeasured commentary one sees on Twitter.

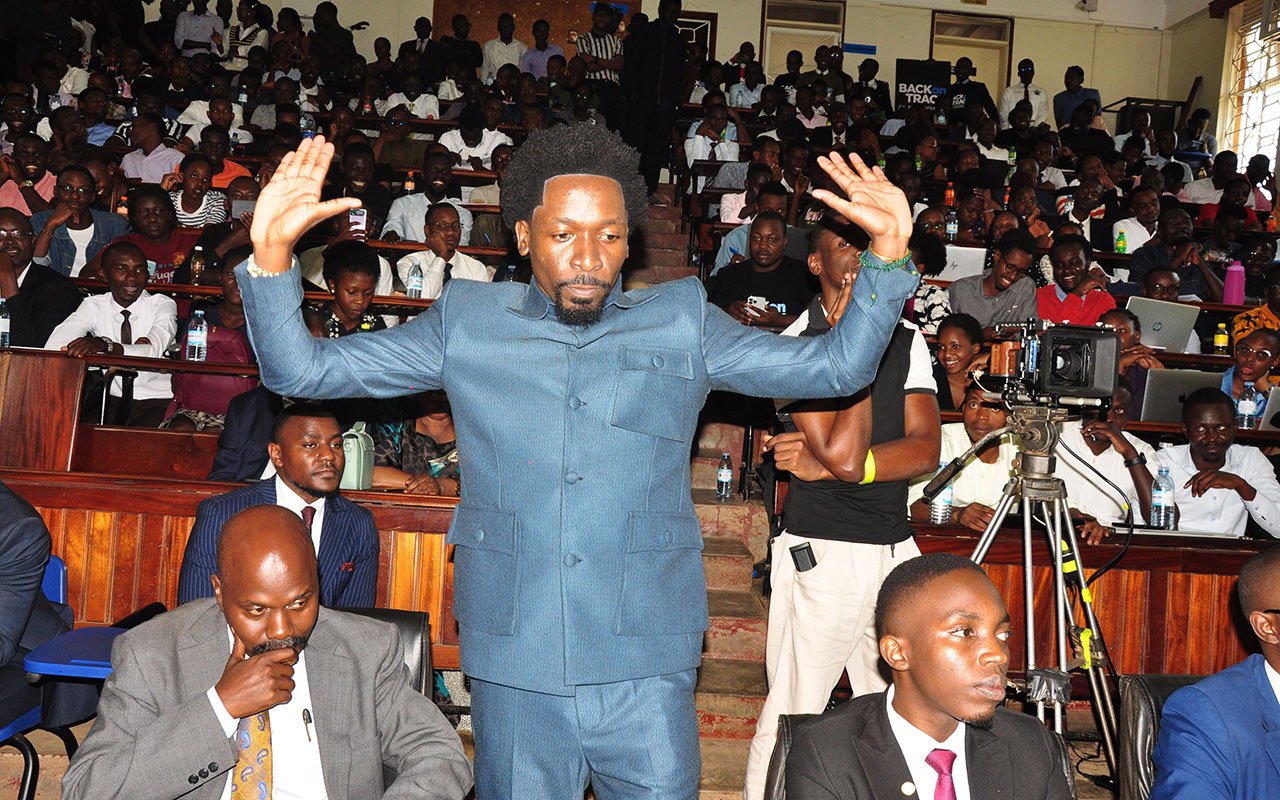

As a matter of principle, if I had a vote I wouldn’t cast it for the man who emerged the winner and is now ULS president – Mr Isaac Ssemakadde. It is not just the modus operandi, of unruliness and sheer intellectual indecency, it is also that there is not much substance, strictly speaking.

Sloganeering and shouting big words is one thing, grasping the complexities of a situation and having the strategic foresight to tackle it, is quite another.

When challenged on matters of substance, there is an instant pivot to unwarranted insults. Your columnist has received a share of the cheap ad hominems that effortlessly flow from the man now heading Uganda’s venerated Bar association, in a profession otherwise defined by decency in discourse and respectful disagreement in the public sphere, especially in the courts of law.

There is an illusion that a rebellious president of the Law Society will turn tables on a broken judicial system and bring about true rule of law. This article of faith betrays a degree of infantilism or, at worst, denotes a certain level of intellectual dishonesty, or at a minimum a blithely failure to come to grips with Uganda’s current treacherous political landscape.

For all practical purposes, Uganda today is under a less than disguised military dictatorship where, in the final analysis, it is the might of the gun not the force of law that prevails. Our rulers have always had a flirtation with the twin doctrine of the rule of law and constitutionalism, no doubt.

In fact, we were told the reason they took up arms in 1981 to fight and capture power in 1986, through the barrel of the gun, was precisely to bring about democracy, rule of law, human rights and all those lofty liberal precepts. To follow through with this promise, a widely consultative constitution-making process that started in 1989, chaired by Justice Benjamin Odoki, culminated in the promulgation of a new constitution in 1995.

It was billed as a ‘people’s’ constitution. Despite many flaws, especially the suspension of political party activities while the so-called Movement system was in place, the 1995 Constitution was generally a progressive document, a corrective step in a country heretofore scarred by misrule and violent abuse of power.

It had a whole bill of rights, elaborate checks and balances, several accountability institutions, perhaps most importantly the provision of presidential age and term limits meant to facilitate peaceful change of power at the top, an elusive feat never experienced since Uganda gained independence in 1962.

Barely 10 years later, through sheer manipulation and blatant deceit, the term limit provision was deleted from the Constitution, paving way for not just the entrenchment of a life-presidency of Gen Museveni, but with it the crashing of constitutionalism altogether. Since 2005, Uganda has been on a steady decline.

The constitutional consensus embodied in the 1995 documented became largely eviscerated .Today, civilians are hurled into military courts and imprisoned indefinitely in total disregard of the law and constitution.

Court orders are flagrantly ignored. Senior army officers, especially the Chief of Defence Forces, utter statements that patently offend both the letter and spirit of the law with no consequences, not even a whimper of a reprimand.

While we had a series of progressive decisions from the Bench during the late 1990s through the 2000s that pushed the frontiers of freedom and democracy in Uganda, we now have a judicial branch that is fully under capture. It is a capture powered by force and finance, the two core sources of Museveni’s rule.

There are circumstances under which litigation and judicial activism can help push a country in the right direction. We previously had a bit of that. Not Uganda of today. What we have now is a political system underpinned by militarism and crass pursuit of power, to which the Judiciary is subordinate.

The rule of law is followed only where it’s convenient and where the interests of the rulers are not threatened. We are not a law-governed country. The holders of state power, and their acolytes do not abide by basic laws and court decisions.

Absolutely nothing happens to them when they, for example, flatly ignore a ruling of the Supreme Court! In the current circumstances, a head of the Bar association hyped as ostensibly on a revolutionary mission to overhaul the ULS is most likely overpromising and will probably under deliver.

Until there is a turnaround in Uganda’s political trajectory, a shift from militarism and the impunity of the gun to a civil political landscape of constructive discourse and dialogue by all political actors, the Law Society will make the loudest noise ever and lawyers will make eloquent submissions in courts, but the rulers will rule as they please.