Prime

The perils of kleptocracy

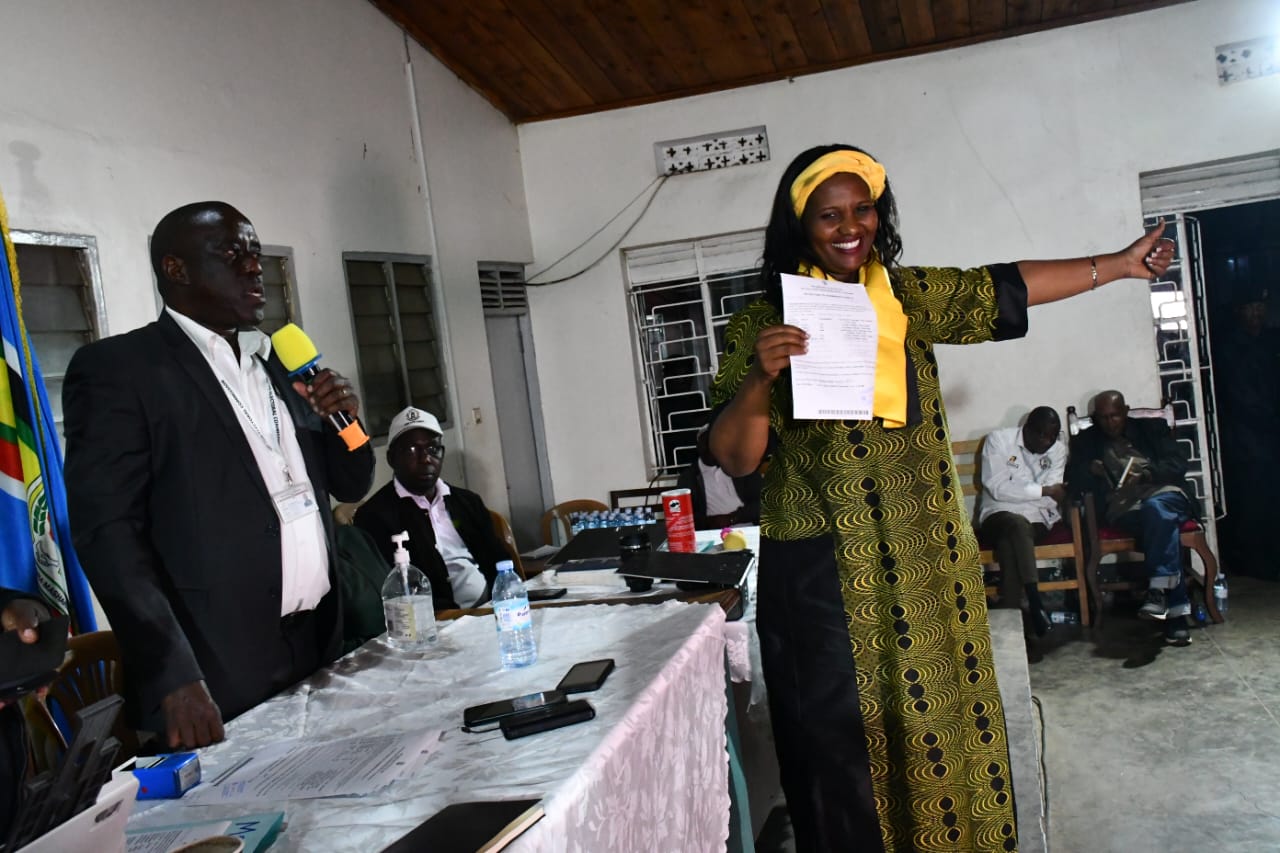

Author: Moses Khisa. PHOTO/FILE

What you need to know:

- In the final years of Mobutu’s endemically corrupt rulership, military aircrafts were openly used as commercial ‘flights’ from which uniformed personnel paid themselves in lieu of official salaries.

At the peak of its decay and dysfunction, the Mobutu regime in Congo-Zaire was considered emblematic of kleptocratic rule. Kleptocracy is essentially a system of rule built on runway corruption. The public good and national interest are subordinated to individual profiteering and private material interests.

In the final years of Mobutu’s endemically corrupt rulership, military aircrafts were openly used as commercial ‘flights’ from which uniformed personnel paid themselves in lieu of official salaries.

Other military equipment and tools, including guns and ammunition, were handy sources of income. Bureaucrats, from the top to the lowest levels, used whatever authority or official power they held to extract and extort. They collected unofficial revenue in exchange for public services but the revenue went to private pockets. This was so pervasive that it was an exception to find otherwise.

Even though it became the Democratic Republic of the Congo following the ousting of Mobutu, signalling an attempt to break with the ancien-régime and forging a new Congo, considering how deep-seated Mobutuism was, the Congo never extricated itself from the rule of corrupt elites and business cabals.

The country remains trapped in a system where a tiny minority profiteers while the majority burns in the furnace of poverty.

Corruption whether by the elite classes, which tends to be grand, or the lower classes in government and across society, which is petty, is a phenomenon pretty much found everywhere in the world. In almost all governments and authoritative systems, there is corruption and abuse of authority. The difference is the degree, magnitude, and consequences.

Rich and powerful countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom have their brands of elite corruption. In the US, the euphemism used is ‘campaign financing’, or lobbying.

Corporations and business interests donate money to politicians and parties, and in return, the donors benefit from favourable legislations and policies. This corruption can be in billions of dollars but is fundamentally different from corruption in Congo or Uganda.

For the most part, it does not directly hurt the wider public good but yields private gains to those who donate to politicians: they get tax cuts, paying less in taxes than they should. This kind of corruption does not involve theft of public funds allocated for a public good or service like a road or national defence.

Middlemen/women are paid retainers and commissions to use their networks and connections in influencing government decisions and policies to serve certain business interests. Public office holders will supervise agencies with oversight and regulatory authority in areas where the very supervisors have business interests and stakes.

These are all corrupt practices but not of the type in Mobutu’s Zaire or today’s Uganda where the use of public office to line one’s pockets necessarily means the public interest is hurt and the citizen is harmed directly.

Looking at the system of rule in Uganda today, it is difficult to see it any other way than a kleptocracy where an elite cabal siphons public funds for private enrichment, where nepotism and cronyism are in harmony with money deals that serve the interests of rulers and their handlers.

Social media is now as much a cesspool of fabrications and falsehoods that go viral as much as the unfettered flow of useful information, but without it, we would unlikely see the many shocking letters written by Uganda’s head of state directing the prime minister or the minister of finance to handle this financial matter and the other involving private individuals.

Thanks to social media, it’s easy to leak such letters. They keep coming, ever shocking. A recent one involves a businessperson whose company retails petroleum products. In the letter, the president directs a subordinate member of his government to look into the possibility of the government buying 15 acres of land in Mukono, near a railway line, so as to help the business/family facing distress and unable to service debts.

Anyone who knows the real estate market in Uganda would know that 15 acres of land in Mukono, never mind that being near the railway is itself quite suspect, is not the kind of property value that can bail out a distressed big business.

But that is not the problem here, the issue is that such a presidential directive opens up a clear avenue for all sorts of scheming, middlemen-dealing, and bribe-solicitation by a long line of actors. In the end, if the actual market value of the land in question is Shs100 million an acre, the government will actually pay ten times!

Once a country is engulfed in both grand and petty corruption, as Uganda is today, the entire governmental apparatus is eviscerated, and public interest is compromised. It’s difficult for the country to get out, but the system has a lifespan – ultimately, it crashes, one way or the other. Rebuilding functional and credible authority after that will be herculean.