Prime

Unesco committee autonomy at stake

What you need to know:

I have been associated with the Uganda National Commission for Unesco for more than two decades; six of them as a member of the culture committee and four of them as the chairperson of the culture committee, hence my passion for its existence in its current form as a semi-autonomous entity

During the parliamentary sitting of July 23, the Deputy Speaker, Mr Thomas Tayebwa, read to the House a letter from President Museveni, on the future status of the Uganda National Commission for Unesco. The import of the letter was to the effect that Uganda National Commission for Unesco be made a unit in the Ministry of Education and Sports.

I have been associated with the Uganda National Commission for Unesco for more than two decades; six of them as a member of the culture committee and four of them as the chairperson of the culture committee, hence my passion for its existence in its current form as a semi-autonomous entity.

Since November 16, 1963 when the UNATCOM was created, it remained passive until about the mid-1990s largely because it was an integral unit in the ministry of Education. This may be attributed to the civil service method of work and policy guidelines. It may also be attributed to lack of independence from the government.

But Uganda did not get the opportunity to leverage the benefits accruing from UNESCO through the National Commission because of its lukewarm status at the time. Even visibility of UNESCO itself in Uganda was hazy because UNATCOM was not active.But why did Unesco adopt the concept of National Commissions in the first place?

When the International Institute of Intellectual Cooperation (IIIC) was established under the League of Nations in Paris in 1924, it developed the concept of National Commissions. Those Commissions were set up in some 30 countries to promote international cooperation and were mainly composed of educators, scientists and representatives of non-governmental organisations. Based on this experience, the draft proposal for the constitution of Unesco, elaborated in a first form by the Conference of Allied Ministers of Education (CAME) and adopted in London in November 1945, also included provisions for the establishment of National Commissions for Unesco.

At its founding, Unesco gave much latitude to governments in fulfilling their duties as members of the organisation and included a general statement on the nature of National Commissions in the constitution in order to ensure that the representatives of government and non-governmental organisations would work hand in hand to promote Unesco’s goals at the national level and sit side by side at the Executive Board and the General Conference to jointly voice or promote the position of their countries.

This was a truly forward-looking approach to allow non-governmental organisations to have a say in an inter-governmental institution. Therefore, National Commissions ideally should not be part of a Ministry because their functions and composition cut across many ministries, and this is their strength. The commissions have five programme committees to wit: Culture, Education, Natural Sciences, Social and Human Sciences, and Communication. A hosting ministry, like the ministry of Education, in our case, should, therefore, not take over the National Commission and turn it into a unit or department because this would definitely stunt its performance, and the country shall suffer the consequences – as was the case between 1963 and mid-1990s.

Article VII of the Unesco Constitution stipulates that “each Member State shall make such arrangements as suit its particular conditions for the purpose of associating its principal bodies interested in educational, scientific and cultural matters with the work of the organisation, preferably by the formation of a National Commission broadly representative of the government and such bodies”. It further states that the commissions “shall act in advisory capacity to their governments in matters relating to the organisation” and “shall function as agencies of liaison in all matters of interest to it”. Thus, it is the constitutional obligation of each Member State to set up a National Commission. Established by their respective governments, National Commissions should act as “meeting places” and “connecting bridges” between national authorities and a broad range of national bodies and experts in Unesco’s fields of competence.

While the realisation of Unesco’s goals is primarily entrusted to governments, the National Commissions are expected to function as an indispensable platform where national interests, ideas and cultures are represented.

Lastly, a legal instrument outlining the National Commission’s structure, composition, and working conditions is essential. This document helps establish the Commission’s authority and it involves a government formalising its decision through decrees, laws, or ministerial resolutions. A National Commission usually has its own constitution, endorsed by the government and sometimes approved by the national parliament.

Based on the foregoing, I implore Members of Parliament to persuade the President to reconsider Cabinet’s decision of making UNATCOM a unit within the Education ministry.

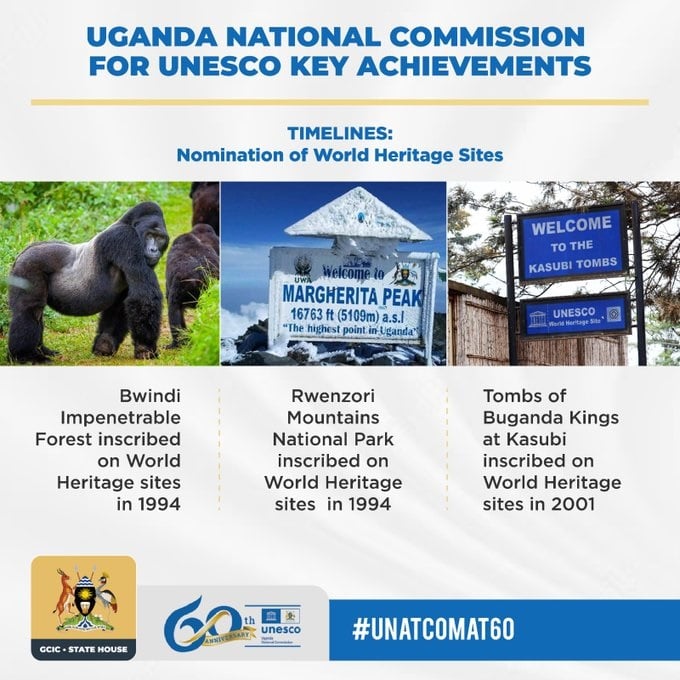

Since assuming semi-autonomous status and an Act establishing it, UNATCOM has helped revolutionalise the five programme committees through grants from Unesco.

James wasula

0772501487