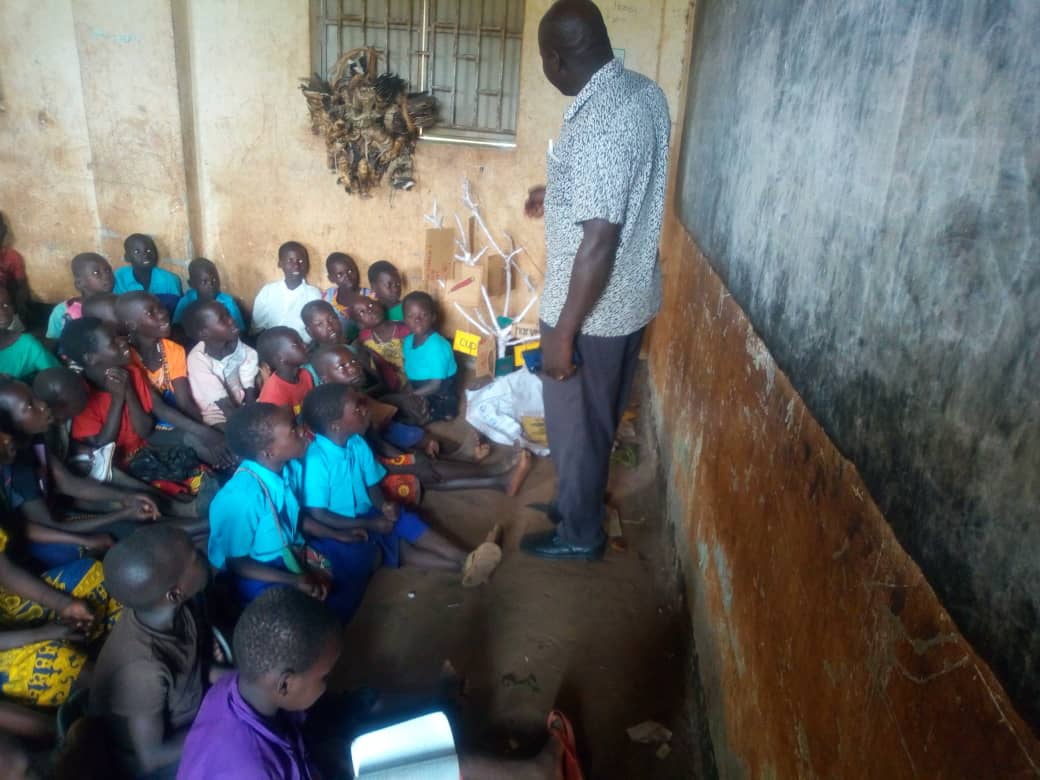

Pupils of Aketket Primary School in Lalogi Sub-county, Omoro District, attend lessons in June 2024. PHOTO/TOBBIAS JOLLY OWINY

A report by the Auditor General says the government’s free-for-all primary education scheme is still struggling to impact the country’s quality of education, 27 years after it was rolled out.

The government announced the rollout of the Universal Primary Education (UPE) programme in 1996.

But a 2023 value-for-money audit report says whereas considerable progress has been achieved in enhancing access to education, there remains inadequate regulatory, institutional framework, and associated policies to support the implementation of UPE.

The report by Auditor General John Muwanga also cites lack of adequate school infrastructure and learning environment, and unpreparedness in teachers across the country to deliver effective pupil learning.

The audit established that while Section 1(a) of the Education Act, 2008, effected the UPE policy, the Ministry of Education and Sports (MoES) ministry has not conducted any comprehensive review of the programme since 1996 to document the gains, challenges, and lessons learned to inform policy adjustments.

“Since the introduction of UPE in 1997, no comprehensive evaluation of the programme has been conducted by MoES. The above was caused by a misconception that a government White Paper was equivalent to a policy and addressed all aspects that a policy would,” the report stated in part.

It also said once the government introduced the UPE programme to all children in the country, the government also introduced supporting policies to guide the implementation of the programme, including the automatic grade promotion policy, the abolition of the Parent Teachers Association (PTA) charges, and the policy to have one public primary school per parish.

The report said, these fresh introductions, notwithstanding, there have not been any related written policies or guidelines on the implementation of the abolition of PTA charges policy, the automatic promotion policy, and the one public primary school per parish policy we established.

During the assessment, the auditors realised that while the ministry confirmed the government had decided to abolish PTA charges, a failure to harmonize the two positions resulted in ambiguity, resulting in some schools charging PTA fees while others were not.

The Education Act of 2008 permits the management of government-aided primary schools to charge PTA fees with the consent of parents, while the Guidelines on Policy, Roles, and Responsibilities of Stakeholders in the Implementation of UPE 1998 fixed the PTA charges in urban schools at Shs10,400 to cater for administrative and utility expenses.

Out of 57 schools inspected during the audit, 31 (54 percent) charged PTA fees, while 26 (46 percent) did not. However, the auditors observed that in all the 31 schools that charged fees, pupils missed school at least once in the third term of 2023, due to their inability to pay the PTA fees.

“This contradicts Section 9(3) of the Education Act, 2008, which prohibits pupils from being chased or denied access to education owing to failure to pay PTA contributions. This also creates a divide in the learning environment by perpetuating inequality by denying some students access to education while others continue to learn,” Mr Muwanga said.

He said the interruption in learning disrupts pupils’ academic progress and may contribute to a widening gap in educational outcomes between those who can afford fees and those who cannot.

Meanwhile, a lack of written guidelines on automatic grade promotion policy, the audit revealed, resulted in schools implementing it differently.

The report established that of the schools inspected, 5 (9 percent) promoted learners to the next class on merit, 12 (21percent) automatically promoted learners irrespective of their performances, and 40 (70 percent) promoted learners after consultation with parents whose pupils were deemed to have performed below average.

The report said: “For learners whose parents declined guidance from schools to have their learners retake classes, the schools eventually promoted such learners. “This scenario has disadvantaged the academically weak learners, with no opportunity for improvement,” it reported.

Pupils leave a classroom at Gore Primary School in Lapul Sub-county, Pader District, on April 2, 2024. The school lacks enough desks to accommodate the learners. Photo/Gladys Lakareber

In recent years, effective teaching in primary schools in Uganda has become a concern due to numerous factors affecting teaching in primary schools, for example, contradictions in the curricula used by schools.

The MoES, in February 2022, introduced the abridged curriculum for primary education aimed at recovery of lost time during the Covid-19 pandemic and to enable all learners to be brought on board as the schools reopened.

Mr Muwanga said several schools were found to be applying different curricula while others did not have it.

“The use of different curricula was attributed to the assumption by MoES’ management that after the Covid-19 pandemic, the schools would automatically revert to the standard (old) curriculum.

Teaching using different curricula may lead to inconsistent learning outcomes, worsened inequality, and difficulties in pupil transitions, particularly when learners change schools.”

Mr Muwanga said out of the 57 schools audited, Kabingo Primary School in Kamwenge District lacked a curriculum.

“While the teachers at this school were using textbooks and reference materials not aligned with a specific curriculum, of the remaining 56 schools, 23 (41 percent) implemented the abridged curriculum, 26 (46 percent) implemented the standard (old) curriculum, whereas 7 (13 percent), the teachers dithered between both the abridged and standard curricula,” the report said.

The abridged curriculum, which implied a compression or merger of content for some topics, was to be in use for a period of one to three years, for which UNEB was to examine learners to allow a safe transition to the standard curriculum.

The audit also sampled the curriculum of primary four and six and noted that the abridged curriculum was either merged, brought forward, condensed, or deleted some topics.

Monitor has also established that the high pupil-to-teacher ratio in the majority of public primary schools has retarded the quality of learning.

“Analysis of data on teachers and pupils in the sampled schools revealed that the average teacher to pupil ratio was 1:49 in FY2021, 1:55 in FY2022, and 1:55 in FY2023, which slightly was within the recommended ratio of 1:53,” the audit revealed.

While each primary school is required to have at least seven classes with at least eight teachers, including the administrator(s), the audit revealed that most teachers taught on average four courses in a day, resulting in an excessive workload.

Mr Muwanga noted: “The already challenging situation of one teacher teaching a class of 53 learners in all subjects, or a teacher handling four subjects across different classes in a day, worsens due to the increased enrolment.”

The surge in enrolment was also found not to be proportional to the number of available teachers, thus worsening the excessive workload.

“Consequently, as pupil enrolment increases, the teachers’ capacity to focus on individual learners decreases, affecting the ability to supervise and grade the learners’ work,” the report said.

This publication has learned that an acute lack of staff housing resulted in the failure to complete syllabi since teachers had to commute between home and school, sometimes over long distances, causing them to arrive late at school and leave early to reach home before darkness.

For example, the report highlighted the cases of Ruyonza Primary School in Ibanda Municipality, and Kabingo Primary School in Kamwenge District, whose staff travelled between 10 and 15km, respectively, to reach their respective schools.

The audit analysis revealed that out of the schools that had staff housing, 84 (50 percent) of the staff residences were constructed using PTA funding and/or support from development partners.

Inadequate infrastructure

The report also highlighted inadequate infrastructure in schools where classrooms, desks, and toilet facilities, among others, were not enough for the learners.

A makeshift classroom at Lyakabirizi Cope Primary School in Lwengo District. PHOTO | GERTRUDE MUTYABA

In the FY 2021/2022 and 2022/2023, the excess number of pupils in every class was 22 and 24, respectively. The analysis revealed that the classroom-to-pupil ratios varied from one region to another.

For example, the Southern/Western region had an average classroom-to-pupil ratio of 1:48, which was favourable in comparison to the recommended average of 1:53; the Central, Eastern, and Northern/West Nile regions had ratios of 1:65, 1:76, and 1:107, respectively, all above the recommended average.

“To put the ratios in perspective, Got Lembe Primary School, with the worst classroom-to-pupil ratio of 1:280 in FY 2022/2023, would require an additional 4 classrooms to be able to accommodate the current number of pupils attending class. This shows the magnitude of the challenge of a lack of classrooms,” it said.

The Planning, Budgeting, and Implementation Guidelines for Local Governments, Education, and Sports Sector FY2021/2022 require schools to have desks each accommodating 3 pupils.

But the audit revealed an overall average desk-to-pupil ratio for the sampled schools of 1:4 in FY 2020/2021, 1:5 in FY 2021/2022, and 1:4 in FY 2022/2023.

“The above ratios imply that in FY 2020/2021 and 2022/2023, there were 4 pupils for every desk of 3, implying 1 pupil had to attend lessons either while standing or sitting on the floor. In FY 2021/2022, two pupils had to sit on the ground or attend while standing.”

In the sampled schools, on average, each latrine was being used by 62 pupils in FY 2020/21, 65 pupils in FY 2021/22, and 67 pupils in FY 2022/23, which were all above the recommended ratio of 1:40.

For example, the Southern and Western regions, which had a 1:44 latrine-to-pupil ratio in FY 2020/2021, had 1:44 in FY 2021/2022 and 1:48 in FY 2022/2023 (average 1:46).

The Northern/West Nile region in FY 2020/2021 had 1:81, 1:97 in FY 2021/2022, and 1:94 in FY 2022/2023; while the Central region had 1:65, 1:58, and 1:66 in FY 2020/21, 2021/2022, and 2022/2023.

Worrying dropout rate

The Ministry of Education and Sports says, currently, the primary education completion rate stands at only 32 percent.

Dr Joyce Moriku Kaducu, the State minister for Primary Education, who admitted to a regression in the government’s free education initiatives, said: “Only 32 percent progress up to P7. And out of 32 percent, some of them do not sit PLE. Many of our children drop out after P7, even though the dropout rates before P7 are very high. We need to examine ourselves; it should be a moment of soul-searching.”

She was officiating at celebrations to mark 25 years’ (silver jubilee) of UPE in the country at Gulu District Council Hall, mid-August 2023.

Poor literacy

The 2021 Uwezo National Learning Assessment (Uwezo Uganda, 2021) cites over 25 percent as the fraction of primary three children who could read nothing from a primary two-level English story, and another equivalent 25.8 percent could only read letters and not words.

Overall, for the primary level (Primary 3 to Primary 7), at least 11.6 percent of the children could not read anything from a primary two-level English story, an increase from 6.2 percent in 2018.

A May 2023 research conducted by the Economic Policy Research Centre of Makerere University pointed to critical gaps that have continued to frustrate the programme, yielding limited fruits.

Mismatch, shallow content

The report titled, Improving Education Systems in Uganda: Evidence from the Primary Education Sub-Sector’, attributes incoherence between the instructional materials, the programme design and misalignment of the examinations issued to learners with the curriculum, among others.

“On the transition curriculum, is inappropriate and over-ambitious because the learners find it difficult to quickly switch from the local language, a medium of instruction in lower primary, to English. Learners find subjects strange as they are used to themes in lower primary,” it says in part.

“There are cases of private supplies of instructional materials that are not regulated by the Ministry of Education and end up producing material that is misaligned with the curriculum, examinations, and students’ learning levels.”

The researchers also pointed out that, overall, the recommended textbooks (under the programme) have shallow content and are irrelevant since relevant stakeholders like the district education authorities and schools were not consulted in developing and deciding which materials to supply.

“We discovered some cases of mismatch between the instructional material and student learning levels, as the vocabulary used in some instructional materials is sometimes tricky for learners to interpret.

The kind of exams administered to learners at the primary level, the researchers said, is not properly aligned with the curriculum.

“The exams that learners are subjected to are not in line with syllabus coverage or topic alignment as per the curriculum. This is because they have left the setting of exams to the private sector.”

“These examinations rarely balance out questions and focus more on the lower-order levels of cognitive demand, for example, the knowledge level, which involves memorization other than comprehension,” the report added.

“Whereas theme-based learning is appropriate for learners, the curriculum currently involves handling too many themes beyond the learners’ capacity. This makes the subjects complex and challenging, leading to high dropouts and repetition in this class,” it concluded.