Prime

How Museveni has stayed in power for this long

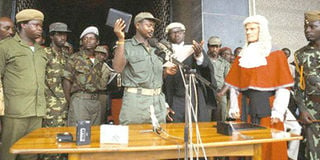

Mr Yoweri Museveni swears-in as President for his first time in 1986. Tomorrow, he swear-in as President for his fifth elected term. File photo

What you need to know:

30 years and counting. Tomorrow Mr Museveni will take his fifth oath for the office of President of the Republic of Uganda. The swearing-in ceremony comes with a cocktail of reactions and thoughts.

It is Museveni again. These words were the headline in the Daily Monitor a day after the Electoral Commission declared President Museveni winner.

The President took issue with the headline, berating this newspaper’s editors for the choice of words, interpreted in his worldview to imply fatigue with yet another five years of his presidency. He was jovial though at the press conference hosted at his country home in the western part of the country, teasing this newspaper how he had defeated it and joking at one point hell was after all a fair destination for its reporters who remained under God’s watchful eye.

As he saunters to the rostrum tomorrow to take his fifth oath for the office of president of the republic, Mr Museveni’s swearing-in ceremony comes with a cocktail of reactions and thoughts. He is an ageing man, walks less faster, speaks with more deliberation and envelopes his words in what some consider old narratives. For Ugandans born after he came to State House in 1986, more than three thirds of the 35 million population, the headline, “It is Museveni again” will be playing in the minds, a reminder for those who want to see him hand over power.

But where the question remains: “How does Museveni do it?” To this day, there is no single book that takes a comprehensive look at how Mr Museveni has dominated the Ugandan State for more than half the time it has been independent (since 1962) and for more time than all past leaders combined. So intricate is the Museveni and Uganda story that if it were told uncensored, the book would be one of Africa’s most intriguing human works.

A newspaper article would only essentially do a bird’s eye view attempt at entering this world of Mr Museveni the summation of which, according to various sources we spoke to, rotates around his character and how he fits or has fitted himself into socio-political factors at play but also agreeable achievements, at least in the eyes of his defenders.

Former leader of the Opposition in Parliament, Prof Ogenga Latigo, traces Museveni’s successful hold onto power to history, advancing the argument that when he took over State control in 1986, Mr Museveni shrewdly secured the hearts of key communities pivotal in the balance of power in Uganda.

“He rooted his ascendancy to power on critical communities like Buganda who were bitter with Dr Apollo Milton Obote by restoring kingdoms. The west had the intellectual capacity and resource base to keep him in power while he also exploited the hatred Okello Lutwa, Idi Amin and Obote had stirred against the north,” he says.

Indeed to this day, even when Buganda’s relations with central government have sunk to their lowest, Mr Museveni continues to beat his opponents in the vote count in Buganda. Ahead of the 2011, election for instance, government shut down Central Broadcasting Services (CBS) and arrested several demonstrators, dehumanising influential leaders such as current prime minister Charles Peter Mayiga, MP Betty Nambooze, Mr Medard Ssegona and a host of others. Buganda rewarded, rather than punished Mr Museveni, handing him a victory at both the presidential vote and for MPs who stood on the National Resistance Movement ticket.

At one point, the President had complained that the Kabaka was not picking his calls anymore and yes, that spoke to the under currents of tension between the two institutions. Somehow, the hangover of the return of kingdoms, which Mr Museveni plays as a card to keep Buganda in check and a sense of entitlement for reciprocated love from them, seems to play in his favour.

Separately, Mr Museveni’s politics has secured him a place in the north, which in the 2006 election in a protest vote against his government’s failure to protect the lives and property of the land, saw Dr Besigye triumph in the region and Teso sub-region in the east. Mr Museveni has tried to bring the region into his good books.

Upon ascending to power, for instance, Mr Museveni’s regime moved to subtly recreate the Ugandan State in the image of the National Resistance Army (NRA), allowing the National Resistance Council to run as Parliament and extending the NRA bush court system to the traditional Judiciary by putting in place Resistance Councils and Committees to adjudicate civil disputes and at one point, an idea was mooted to extend their jurisdiction to criminal matters.

In a paper titled ‘Popular Justice and Resistance Committee Courts in Uganda’ published in 1994 by Makerere University law dons Prof Oloka Onyango and Dr John Jean Barya trace an attempt by NRM to popularise justice and democracy, which in essence enabled the NRM system to penetrate the lowest levels of society.

This was adopted in the security apparatus, whose tentacles stretch as far as parishes with (Parish Internal Security Officer). Indeed, critics of the NRM regime point to cadres in the Judiciary, civil service, police, army and every unit of leadership, all, like body organs and systems, functioning to sustain the life of the Museveni presidency project.

Washing away the gains made over the years

“His programmes in the first 10 years on education, agriculture, restructuring local government, were good for the country but like Obote in 1971, who did a lot but wasted it away, all that Museveni did has been watered down, the reason he uses the unsustainable option of violence to keep power.”

Media Centre director Ofwono Opondo opines, “I think majority of Ugandans appreciate a country once deemed ungovernable is governable right from the family to professional level. The perception and reality that he turned the country around is the biggest factor. People in Uganda in 1986 were not talking of poverty, they didn’t have basics like salt and sugar, the reason his support from the village to the old speaks to his ability to fix this. He also built the State apparatus capable of picking information to mitigate conflict.”

But former minister in Milton Obote II administration (1980-85) in charge of cooperatives Yonasani Kanyomozi says, “He has guns, money and he smashed the Opposition by keeping them in cold storage for 20 years.” Until 2005, political parties in Uganda were in abeyance with the Movement system holding sway. Critics argue that even after allowing parties onto the stage, Mr Museveni has reduced breathing space for them to effectively mobilise.

“Those who followed him didn’t know his programme and realised it late. His programme was to seize power, retain it at all costs. They assumed he had a programme for the country but those assumptions were wrong,” says Mr Kanyomozi.

Uganda People’s Congresss’ Dr James Rwanyarare attributes Museveni’s longevity to the fact that he has kept the country under “military dictatorship”. The army and police remain one of the best funded aspects of his government.

Mr Museveni continues to run the security forces with effectiveness that could compare to only a few. His stay in power, his opponents opine, is largely a function of the security agencies and their ability to assert authority, project fear and when need arises, as happened with the Walk to Work demonstrations, crude force to put the Opposition down.

Meanwhile, development economist Dr Fred Muhumuza says, “Museveni is a visionary butt at a personal level and not for the country, he is good at building teams that reflect different situations. He has good foresight for what will come mainly for political survival than anything else and assembles teams to do that.”

Former Ethics minister Dr Miria Matembe, however, told this newspaper in an interview that “he is highly skilled at cliqueism (sic) and manipulation… He knows how to read Ugandans, divide and rule and manipulate them. He is calculative, and has mastered the art of being double faced and multifaceted, it is embedded in his character, he exploits your innocence and genuineness after sapping you.

He is a user and that is what has kept him around.”

Some of Museveni’s closest men like former prime minister Amama Mbabazi, former army commander Mugisha Muntu who have since fallen off the cliff attest to the description Dr Matembe accords Mr Museveni. But Mr Frank Tumwebaze, the outgoing minister for the presidency disagrees, “The President has managed to steer the country for this long because of providing good leadership.”

The minister, who belongs to Museveni’s new found generation of allies, those who bear the hope to run the State with no baggage of entitlement and looking at Mr Museveni as a first among equals that the Bush War comrades come with, says, “The 33rd USA president Harry Truman comes to mind when he said that in periods where there is no leadership, society stands still, progress occurs when courageous skillful leaders seize the opportunity to change things for the better. And so Mr Museveni continues at the helm.