Prime

Paternity testing: How it was handled historically

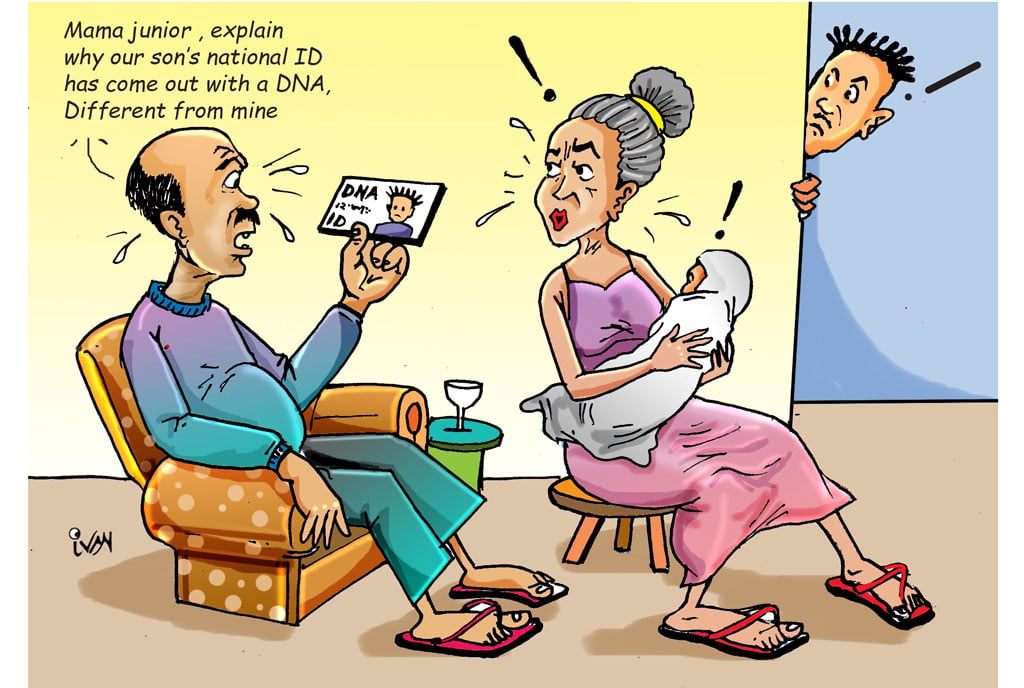

In some cultures such as in Teso Sub-region, tradition dictates that children born out of wedlock, as well as those sired in extramarital affairs, have a place in the immediate family or clan setting in question. PHOTO/TOBBIAS JOLLY OWINY

What you need to know:

- While DNA testing appears to be all the rage, a number of cultural leaders and elders Monitor talks to warn that science could put the country on a slippery slope.

The Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) testing craze that has in recent weeks retained a dark grip on men in Uganda is not only peculiar to the country’s capital, Kampala.

On Queens Avenue, Plot 15, sits a medical testing facility famed in Gulu City for paternity testing.

The Lancet Lab conducts DNA examinations to help families, and men ascertain the paternity of their children.

This week, Monitor learnt that an additional 21 clients visited the facility between April and May. Their search for answers pushed the number to 113, up from the 92 visitors it registered in February and March.

While DNA testing appears to be all the rage, even outside the bounds of Kampala, a number of cultural leaders and elders Monitor talked to warn that science could put the country on a slippery slope.

This is especially the case in Teso Sub-region where tradition dictates that children born out of wedlock, as well as those sired in extramarital affairs, have a place in the immediate family or clan setting in question. This is provided the woman at the centre of the saga is duly married.

Iteso tradition

Mr George William Alloch, one of the founding members of the Iteso Cultural Union (ICU), told Monitor that when a daughter gave birth to a child while at home, the person responsible for the pregnancy had to pay one bull or cow in case he entertained the thought of marriage.

Mr Alloch adds that if it was discovered that the aforesaid person was not responsible for the pregnancy, he was still mandated to pay one cow. He would also assume responsibility for the upbringing of the child in question.

“These children were valued and had a share of inheritance allocated to them,” Mr Alloch says, adding that "the change in approach could be down to soaring living costs."

The founding member of ICU recollects the time when elders would marry as many wives as possible. In the process, they would enlist the help of boys in the community.

“These boys were allocated to respective wives, and their help was not only limited to garden work but they were also mandated to perform night duties,” Mr Alloch reveals, adding that “those ancient elders knowingly and happily carried children who were not theirs.”

Mr Alloch further divulges that such things happened in silence and secrecy. Nephews would, he adds, father children with wives of their uncles. He suspects that not much has changed; save for the fact that “we live in denial.”

He notes, “We are in a situation where bosses, workmates, supervisors mishandle women. At the end, they produce children who are not yours.”

Mr Tom Patrick Ogwang Anam, the Laki Clan chief, says some men are now going for DNA tests because of selfishness. He adds that in the past, parents would treat children born outside wedlock equally.

“In our culture, when you sire a child with a married woman, the one who paid the dowry is the father of that child. So, this thing of DNA test is very new and it’s a bad practice. Government should come out and regulate it,” he said.

Mr Alfred Jokene, a resident of Tarogtali Village in Ibuje Sub-county, Apac District, says a child born outside wedlock was like a gift to a family.

“In the past, our forefathers would value children so much but currently, many parents do not want to take care of children who are not theirs. This is because of the issue of land and paying school fees. It is boy children who suffer most,” he said.

Mr John Ogwal, a resident of Abapiri in Chawente Sub-county, Kwania District, says a child born outside wedlock should be treated well because that child is innocent.

“Taking a child for a DNA test because you suspect that child to have been produced by another man subjects a child to psychological torture, so it must stop. Children should not be punished for the mistakes made by their parents,” he said.

Bakonzo tradition

In the Bakonzo tradition, children are considered to belong to their patrilineal lineage, and they are primarily associated with their fathers.

Erikanah Baluku, the culture minister of the Rwenzururu Kingdom, says it is not acceptable for a woman to bear children while still residing at her father’s home, “she would be questioned about the man responsible for the pregnancy, and she would be sent to that man’s family so that she doesn’t give birth under her father’s roof.”

“If a person goes for DNA, it means he wants to either separate from the wife or the child and that there is a misunderstanding in the family and culturally, it shows that a man is scared or threatened and wants to belittle his wife because sometimes women become kings in the family.”

A child born out of wedlock is considered as an outsider who does not belong to the family, and the woman is tasked to look for the father of that child. And the woman is forced to leave the family, he says.

According to Bakonzo’s beliefs, anyone who comes from their mother’s bedroom is considered their father, and thus, they are expected to show equal respect to both their biological and stepfathers.

Southwest Uganda

Among the Bakiga and Bahororo communities of southwestern Uganda, children born under such circumstances are not respected by the community members. Saturday Monitor established that such children are always referred to as ‘ebinyandaro’ (loosely translated to mean someone homeless with no family attachment).

Mr Christopher Namara, the Kabale District community development officer, says almost all children born courtesy of extramarital affairs are not officially accepted.

“Every week, we register about one case of child abuse and when we dig into the matter, we find that the child being abused was the product of an extramarital affair. Mothers of such children always complain of being denied property after the death of the fathers of their children,” Mr Namara says.

Sheikh Kabu Lule, the Kabale Muslim district Kadhi, says although Muslim children born thanks to extramarital affairs are welcome to the Muslim faith; they are not allowed to share property after the death of their father under Sharia laws.

“Under Sharia laws, it’s the father to be punished. Such children are not allowed to inherit property from their deceased fathers, although the father can decide to give them properties before his death,” Sheikh Kabu Lule says.

West Nile

In the West Nile Sub-region, a number of children are the product of extramarital affairs. According to Mr Yassin Ari, an elder in Yumbe District, “there are cases where some children are produced accidentally through commitment of rape or defilement and the mother may keep quiet over such happenings.”

He adds: “In a case where there is a resemblance of the children, the process of DNA test comes in, which was not there in the past.”

Mr Ismail Tuku, the prime minister of the Lugbara Kari, says the paternity of the child was always determined by the mother.

“Whatever the mother declared was never challenged,” he says, adding “that is why we have names like ‘Izimandri’ (loosely translate to mean ‘you ask the mother’). But where there was disagreement, sometimes it could end in divorce.”

Acholi tradition

Elsewhere, among the Acholi people of northern Uganda, adultery was classified among the worst crimes a married woman committed in her house. In fact, it usually culminated in either a divorce or rituals that would cost the life of the child who is the result of an extramarital affair.

Mr Martin Otinga Otto, the Lamogi clan chief, nevertheless, says the clan holds in equal regards children born in wedlock and those sired as a result of extramarital affairs.

“It is a choice for the man to seek divorce or continue with the marriage. We did not and we do not condemn such children since they are innocent,” he says, adding, “As a man, all children your wife sires in your house after marrying her are your children irrespective of their paternity.”

Mr Kasemiro Okwir, the Patongo Clan chief, says DNA tests were not significant due to the polygamous nature of the society.

“DNA testing is a completely new development. In our setting, if I had many wives and a visitor came, I would offer one of my wives to provide them comfort and sometimes they even sired children in such circumstances,” Mr Okwir says, adding that children were embraced regardless of paternity because they offered a semblance of security.

LISTEN NOW: What’s behind rush for DNA tests?

Mr Okwir details circumstances under which brothers, cousins and relatives are allowed to sleep with and have children with a woman married to a particular family.

He says sometimes the man went AWOL for years or was simply impotent. In which case, his near relatives are asked by the elders to have sexual relations with his wife.

“In both cases, rituals are performed. If the man is impotent, he is advised by the family to pick one of his brothers or nephews to agree and sleep with the woman, upon counselling the woman. He comes and sleeps there for the period that the woman is ovulating, that child is for the husband of the woman,” Mr Okwir says.

Litmus test

When a woman was, however, suspected to have had a child courtesy of an extramarital affair, they undertook a ritual in which she was made to hit and slit a piece of wood from a unique tree using an axe.

“A failure to hit the wood implicated the woman of the crime and she was divorced,” Mr Augustine Ojara, an elder in Gulu City, discloses, adding, “In the past, and even today, we do not need DNA testing. If a man or family was not sure of the paternity of a particular child and suspected the woman to have had an extramarital affair, she undertook an oath and a ritual.”

He adds: “In that oath and ritual, it can only be told that the child belongs to the man if the child survives to live the first two years. Majority of such suspected cases, the children die upon their mothers taking the oath.”

According to Mr Ojara, other women who undertook the oath and ritual, denying conceiving with another man under pressure yet they did, escaped and left their families to save the child or the foetus.

By Tobbias Jolly Owiny, Felix Warom Okello, Clement Aluma, Robert Elema, Simon Peter Emwamu, Robert Muhereza, Jerome Kule Bistwande, Alex Ashaba, & Felix Ainebyoona