Period poverty: The cost of menstruating in rural Uganda

It is still a challenge for some girls to access sanitary pads. PHOTO/ ABUBAKER KIRUNDA

What you need to know:

- Poverty in the rural and urban areas, had driven a number of girls to use anything that can absorb blood as a sanitary towel. Girls have been known to use banana fibres, pieces of paper stacked together, and dirty rags, all of which can have adverse effects on their reproductive system and self-esteem

Every month, a few days before the onset of her menstruation period, Shakira fills a transparent polythene bag with soil. Then, using a needle, she punches small holes into the polythene bag. When her menstruation starts, she wraps an old dirt-brown piece of cloth around the soil-filled polythene bag. This is the sanitary pad she will use for the next five days.

The 17-year-old student, who is a resident of Buyala village, Northern Division, in Jinja City, has been using sanitary pads made of soil for the last seven years.

“When the blood goes through the cloth, the small holes in the polythene bag enable it to penetrate and flow into the soil. Depending on how heavy the flow is, the soil retains the blood for a few minutes. My grandmother taught me how to use this method because my mother does not have the money to buy sanitary pads for me,” she says.

Naigaga’s father died three years ago, leaving her mother with ten children to fend for. She does this by digging in other people’s gardens for a fee. The meager pay she earns is used to buy essentials such as, salt, soap, and off-the-counter medication. In this home, sanitary pads are not a priority.

Re-usable pads that can be used for a year but still some girls can not afford them. PHOTO/ ABUBAKER KIRUNDA

“I am in the netball team of my school and we train every day. However, whenever I am menstruating, I do not play because I cannot run around the field with a soil pad. When I jump, the pad might fall out of my knickers. I cannot concentrate in class, either; because I keep worrying that the blood will soak the soil and stain my uniform. Soil is not good in absorbing blood,” she says.

The Senior Four student adds that the pads she makes from the soil are not comfortable and one takes a long time to get used to them.

“When the soil is wet with blood, it becomes heavy and emits a lot of heat. I have used these pads since I was in Primary Six. In the beginning, I experienced skin irritation, burning, and discomfort around my private parts, but now I am used to it. I can tolerate the irritation,” she says.

Shakira has taught other poor girls how to make pads out of soil and a number of them in her school are using them.

Period poverty

Every month, millions of women and girls around the world menstruate, however, only one in four can afford to buy decent menstrual products. As a result, some girls drop out of school due to the stigma they face during their periods, while others miss classes.

Period poverty is a global issue where women not only lack access to affordable menstrual tools, but they also lack clean toilets and water. World Bank estimates indicate that globally, at least 500 million women and girls lack access to the facilities they need to manage their periods; 1.25 billion women and girls have no access to a safe, private toilet, and 526 million don’t have a toilet at all.

In Uganda, a packet of eight sanitary pads costs between Shs3,000 and Shs3,500. With tough choices having to be made about buying food for the family and buying sanitary pads, many girls in low-income families have resorted to use unsafe products to manage their periods.

Fatuma Namaganda, a 12-year-old Primary Six pupil, uses old pieces of sponge she tears off her mattress as sanitary towels. Namaganda, who lives with her father, says he cannot afford to buy menstrual products. Her father is a subsistence farmer.

“Sponge covered with old cloth is soft and can absorb blood. I use one sponge for the entire day. However, when I am in my periods, I do not go to school because we do not have water in the toilets. Besides, if blood stained my uniform, the boys would laugh at me. I do not want to feel ashamed,” she says.

Namaganda, a pupil of Buyala Primary School, says after tearing off the sponge, she washes it, dries it, and then covers it with a clean piece of cloth. This is to prevent particles from the sponge entering her private parts.

“I reuse the sponge for three months so that my mattress can last a long time. It is the same mattress I sleep on. I request well-wishers to buy for me a sawing machine so that I can make reusable pads for myself and other girls in my village,” she says.

Daily Monitor interacted with other girls in the village who use dry leaves, banana fibers, and papers as sanitary pads.

Dr. Angella Namala, a gynecologist at Jinja Regional Referral Hospital, says because of the sensitivity of the female reproductive system, any material used as a sanitary towel must be clean.

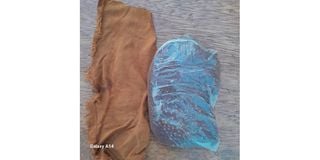

A girl displays the materials she uses while in her menstrual cycle. PHOTO/ ABUBAKER KIRUNDA

“Soil can be good at absorbing blood but it contains many microorganisms, such as fungi and bacteria, which make it unhygienic. Once the soil is exposed to the private parts, the bacteria can get into the cervix, uterus, and fallopian tubes. We have treated a number of young girls between the ages of eight and 15 for recurrent infections because they use banana fibres, dirty rags and anything else that can hold blood, as sanitary towels,” she says.

Dr. Namala adds that these girls expose themselves to the risk of chronic diseases in future.

“They are at a tender age, where the squamocolumnar junction (between the inner and outer cervix) is turning over so often. If they expare exposedose it to these microorganisms, they will affect their ability to conceive if they develop issues with their fallopian tubes and infertility. Girls should compare their private parts to meat. If you keep meat in a moist environment, it goes bad. Meat has to be in a dry environment. That is why sanitary materials have to be absorbent and clean and must be worn in dry underwear,” she says.

Who is failing rural girls?

In 2015, while on the campaign trail in Lango sub-region, President Yoweri Museveni promised that if elected back into power, his government would provide free sanitary towels to school-going girls as one of the ways to boost the education of the girl child. However, the government later backtracked on the promise.

In January 2020, Janet Kataha Museveni, the Minister of Education and Sports, told Members of Parliament on the Education Committee that there was a need for a well-funded national project to sustain the provision of free sanitary pads. The said national project has not yet come into effect. This left many girls, who could not afford menstrual products, out in the cold.

Haruna Mulopa, the education officer of Jinja City, says the only free sanitary pads school children get come from non-governmental organisations.

“I cannot talk about the provision of sanitary towels to girls in schools by the government since I have not seen any delivered to my office. As education managers, we have resorted to advising parents to provide sanitary towels to their children to supplement on the few pads stocked at different schools for emergencies,” he says.

While NGOs have supplied free reusable pads to some schools, parents cannot afford to buy the rest. Ordinarily a packet of four reusable pads costs Shs10,000, a price that is prohibitive to many Ugandans.

A girl wraps a piece of cloth around a polythene bag filled with soil which she uses while in her menstrual cycle. PHOTO/ ABUBAKER KIRUNDA.

Rose Kigere, the executive director of Women Rights Initiative, an organization that produces reusable pads, says poverty is a major obstacle when it comes to menstrual hygiene.

“Our pads can be reused for a year. We thought parents and guardians would rush to buy them because it makes for financial sense than buying disposable pads every month, which cost Shs3,000 a packet. We try to partner with individuals and companies who can purchase our reusable pads and distribute them to schools, but the number of packets purchases cannot be enough to support all the girls in the selected schools,” she says.

Kigere adds that in the nine schools they have so far reached out to, only 250 learners received free pads yet there are many girls in need of them.

“We have noted that parents fear to talk to their daughters about menstruation because the girls might ask them for pads. Some end up disposing off their girls in early marriages so that their husbands can take over the responsibility of their menstrual needs. Girls now get information about menstruation from their peers who are using outdated means of managing their periods,” she says.

The way forward

Over the years, a number of activists have called on the government to scrap taxes on sanitary products to make them more affordable to women and girls, because menstruation is not a choice.

“If possible, condom distribution should be substituted with sanitary pads since engaging in sex is a luxury. Let us have an opportunity cost for condoms and sanitary pads distribution because while one can spend many years without having sex, a period is always on time, every month,” Kigere says.

In a country where millions cannot afford to eat two meals a day, let alone nutritious meals, it would be preposterous to assume that they can spend money on the menstrual needs of their adolescent daughters.

This implies that for a number of years still to come, unless the government intervenes by scrapping taxes on sanitary pads, a number of girls will continue to miss classes and drop out of school because of their menstrual periods.