Prime

Refugees in camps worried over increasing insecurity

Newly-arrived refugees from South Sudan queue to receive daily food portions at the Nyumanzi transit centre in Adjumani.FILE-PHOTO

What you need to know:

- Mr Paul Biggo, the local council chairman of the host community (Angwara Pi village) dismisses the fear of rebels attacking the refugee settlements.

- Although there are a number of agencies initiating peace building and conflict resolution among refugee populations in West Nile, a lot more needs to be done to remove the mutual distrust between the refugees and the host communities over resources.

On Thursday, November 23, 2017, refugees at the periphery of Kyaka II refugee settlement and the host community clashed over a disputed piece of land.

The refugees, led by their administration, carried out an eviction exercise of the nationals from the settlement land and demolished some structures, prompting the nationals to stone them.

As a consequence, according to the Kyegegwa District chairman, Mr John Kisoke, six people were injured when police fired teargas and live bullets.

The security situation in refugee settlements, especially in light of the clashes in Kyaka, is precarious. For instance, with an active civil conflict still going on in South Sudan, for a time, an average of 3,000 refugees crosses into Uganda every day. In a single day – March 9, 2017 – 5,000 refugees were recorded.

However, despite the influx of refugees, the number of police officers in the areas never been increased.

Adjumani District alone has seven refugee settlements with a refugee population of about 209,919. On average, each refugee settlement is manned by three police officers.

Four weeks ago, in Maaji refugee settlement, two teenage boys got into a fight. In any other place, this would have been a normal fight between two overzealous boys from different tribes. But, the Lotuko boy killed the Madi boy, after which a group of Lotuko tribesmen set some huts belonging to Madi families on fire.

Pagirinya Refugee Settlement in Jaipi Sub-county has about 30,000 refugees. The host community has 3,000 residents and all are manned by three police officers. The main language of communication in the refugee settlement is Arabic, although there are more than 20 tribes in the camp.

Kennedy Apenyo, a senior clinical officer, says, of all the tribes, the Nuer are the most difficult to deal with.

“They are controlled from South Sudan and in case of a dispute, they will not agree to mediation unless they are instructed to do so by their leaders across the border. And even then, they can only accept the final solution from South Sudan regardless of what the police have said.

Once, in a clear case of domestic violence, a man broke his wife’s leg in a fight. She was instructed not to report the incident to the police or to seek medical attention. When the leg began rotting, we had to forcefully bring her to the health centre.

However, since she insisted that she had got the injury after falling into a pit, the husband was not reprimanded.”

According to Apenyo, every month, 10-15 cases of defilement are brought into Pagirinya Health Centre III for treatment.

“This is because unlike other camps which strive to hide such cases, we are encouraging the refugees here to talk about crime.”

Inadequate manpower hampering police work

Since September 2017, every camp you visit in Adjumani District has one thing in common – an underlying fear of ritual murderers. These are believed to originate from Arua District and have a mission of beheading refugees and selling the heads to the Democratic Republic of Congo for a purported sum of Shs10million per head.

Agojo Police Post, in the middle of the 8000-strong Agojo Refugee Settlement in ciforo Sub-county, is really just a hut with a cement floor, a desk and two chairs.

At mid-morning, one of the policemen is in his hut, near the station, frying simsim. The deputy in-charge of the police post, Special Police Constable (SPC) Sarah Agenia, is doing house chores and she emerges from her home breastfeeding her baby. None of them is wearing uniform.

“Our challenge is manpower,” Agenia says, continuing, “We have heard about the rumours of ritual murders and all we can do is to sensitise the refugees to move in groups around the camp. The problem is that the health centre is five kilometers away and a return trip on a boda boda costs Shs4,000. As a result, the refugees use a shortcut which is not safe because it is surrounded by tall rocks and bushes. I am also afraid to use that route.”

Mr David Kazungu, commissioner for refugees in the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM), acknowledges that there are manpower shortages for the police in refugee settlements.

“The government is committed to providing security to all the people within its territory. We have written to the police and ministry of internal affairs requesting for provision of security in the refugee settlements and police has provided what they can. We have to work within the systems available to provide what can be provided.”

Mr Kazungu adds that together with United Nations Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), OPM has provided police with vehicles and motorcycles to patrol the refugee settlements and monitor the security situation.

“However, because of the strain on the police, we have gone ahead to do community policing using refugee welfare council systems to make sure refugees are sensitive to their own security. Nationals (host communities) are also facing challenges with the inadequate police resources. The refugees cannot be treated differently just because they are refugees,” he said.

In Agojo refugee settlement, there are not patrol vehicles or motorcycles. Agenia insists that in case of an emergency in the camp, she can always call for reinforcements from Adjumani Police Station, which is 20 kilometres away. The nearest Uganda People Defence Forces (UPDF) detach is eight kilometers away.

The camp is mainly made up of Madi families with a handful of Dinka and Barya, which means chances for tribal wrangles are minimal.

Another issue of concern is that most of the men in the refugee camps in Adjumani are South Sudanese soldiers. They only return to the camp for a period, and then, go back to South Sudan to fight. There is always the fear of retaliation against members of warring tribes.

Mr Bul Garang, the chairperson of 40,000-strong Baratuku refugee settlement in Pakele Sub-county at first denies that there are security concerns in the camp. However, he later says that he is worried about the presence of only three policemen.

“In November 2016, there were rumours of rebels crossing from South Sudan to settle scores in this settlement. When we reported to the police, only 20 policemen came from Adjumani Police Station as reinforcement, patrolled for a while, and then, after a few hours.”

The Settlement, which is mostly inhabited by Dinkas and Acholis, is only 20 kilometers from River Nile, which forms a natural border between Uganda and South Sudan.

SPC Agenia says, “Refugees are screened at the border as they come in, but I cannot be completely certain that they do not have arms inside the camp.”

Mr Kazungu says while military and civilian elements are separated during the screening exercise, there is both overt and covert security deployed in the refugee settlements.

“The situation in South Sudan is unique and there have been stories of military elements that have been identified in the refugee settlements in West Nile, and it worries us that some people may filter through. But at the same time, we have systems in place to identify and deal with them,” he says.

In the Baratuku refugee settlement, the refugees were given pangas (machetes) and slashers by the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) to cut down trees and slash grass in preparation for farming. These seemingly harmless tools can turn lethal in case a disturbance broke out in the camp or a disagreement between the refugees and the host community.

Youth taking over camp security

Mr William Awiyo, the welfare officer of Agojo refugee settlement, has taken matters into his own hands and mobilised 48 youths to man the security of the settlement.

“If there is any incident, the youth in each of the four blocks of the camp deal with it and inform the police afterwards. We do not have enmity between the different tribes in this camp but there was tension between the refuges and the host community. Recently, one of our youths was attacked and cut with razorblades by a member of the host community. We have since called for meetings to resolve the issue,” he says.

Among the settlements reached between the two communities was that there should be no movements beyond 10pm. If anyone is moving from the host community to the settlement beyond that time, the refugees should be informed in advance, and vice versa.

In Baratuku refugee settlement, the youth are also pulling their weight, when it comes to security matters.

“At night, we move around the settlement to find if there are any strangers,” Mr Peter Mayom, a village health trainer says, adding, “Three weeks ago, we ‘arrested’ a strange man and took him to the police post. We do not know what transpired but the police released him immediately.”

Since the youth cannot patrol the camp during the day as well, daily activities have almost ground to a halt. Women are scared of going too far into the bush to collect firewood, and the men are scared to graze their cattle.

However, Mr Paul Biggo, the local council chairman of the host community (Angwara Pi village) dismisses the fear of rebels attacking the refugee settlements.

“There was never a report of rebels; it was just workers from Gulu who had been brought to build culverts. When the refugees saw these workers on trucks, they assumed rebels had crossed into the country.”

According to Mr Biggo, there is rising tension between the refugees and the host community because of the former’s cattle.

“This is going to bring problems. It is a dry season and yet their animals graze everywhere, going into our gardens and destroying our crops. When we try to talk to the refugees, they do not pick advice quickly. They just want to quarrel, insisting that they must keep their animals,” he adds.

Also Mr Biggo is deprecating of the refugees efforts to mobilise youth to protect themselves.

He says: “One time, they said they had arrested a head hunter in the bush, but they do not know everyone in this district. We have told them that they may arrest people who are visiting their relatives in the host community. Instead, they should report the matter to us as opposed to taking their security into their own hands. It is true that the police post has a handful of officers and I am appealing to the government to deploy more.”

Although there are a number of agencies initiating peace building and conflict resolution among refugee populations in West Nile, a lot more needs to be done to remove the mutual distrust between the refugees and the host communities over resources. This can only be done if they are assured of their security in an environment that enables them to be part of the socioeconomic dynamics and the development of the areas in which they have been settled.

Police response

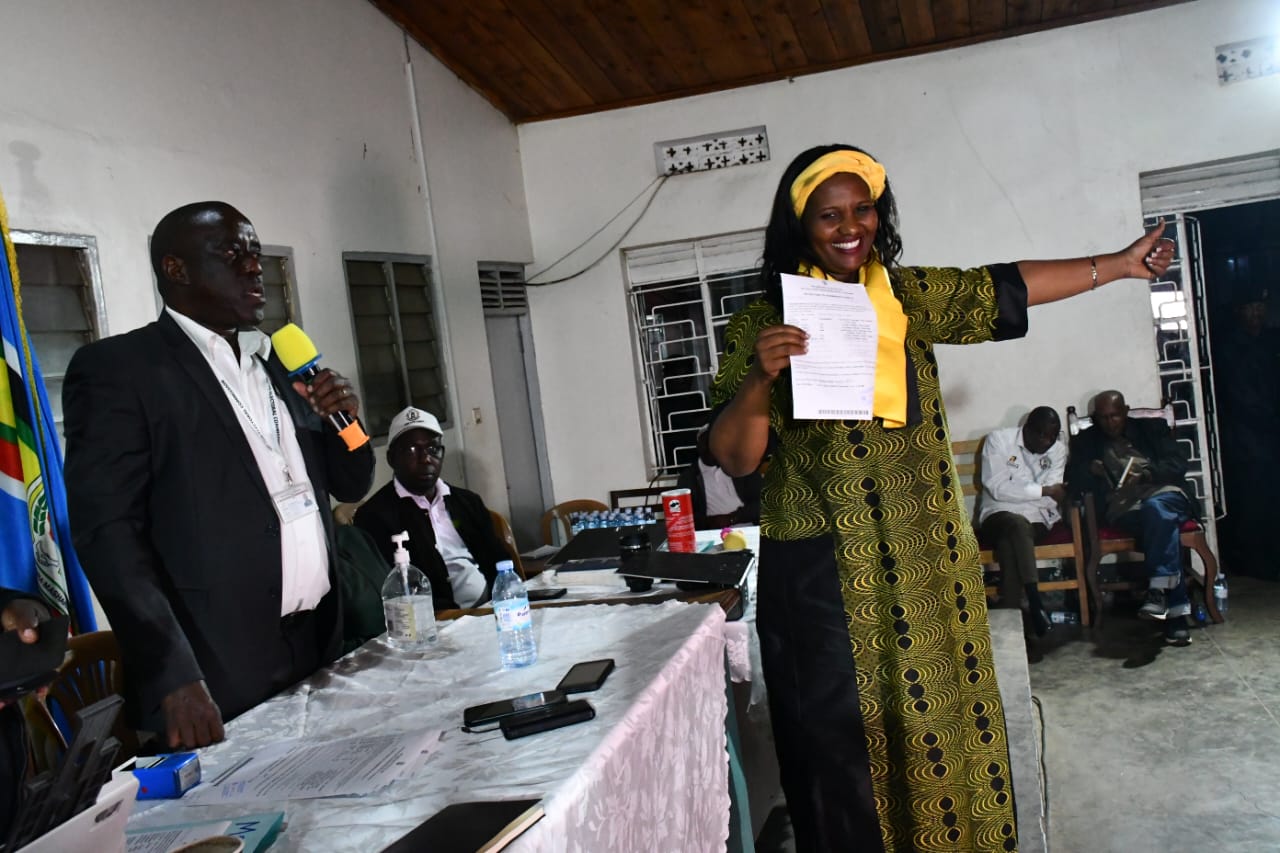

Josephine Angucia, Police spokesperson for West Nile

We have uniformed and non-uniformed officers in the refugee settlements. Besides those in madoadoa (doted) uniform, we have CID and Intelligence officers. If a camp commandant is a civilian, he will not know that there are covert officers in the camp. We also sent crime preventers to every refugee settlement in Adjumani District and they are helping us to coordinate the security situation.

We carry out deployment of officers according to the risk assessment of the specific camp. If we realised that one camp is more volatile, of course we will deploy more officers to it. We do not have permanent officers in the refugee settlements because they are constantly rotated according to the need.

I heard about the incident at Maaji refugee settlement which involved a death and because of that we have many security officers there. But, human beings will always be human beings and you cannot stop a crime from happening. The issue is how the officers will handle the aftermath of the crime.

I have also heard about some refugees being armed in the settlements but it is just a rumour for now. Refugees are screened at the border points as they come in. Those who may be armed may have sneaked through the border using panya (paths) routes. But if they are armed someone will know and will leak the information to the camp commandant. There is no way someone can hide arms.