The death penalty will not make Uganda safer – abolitionists

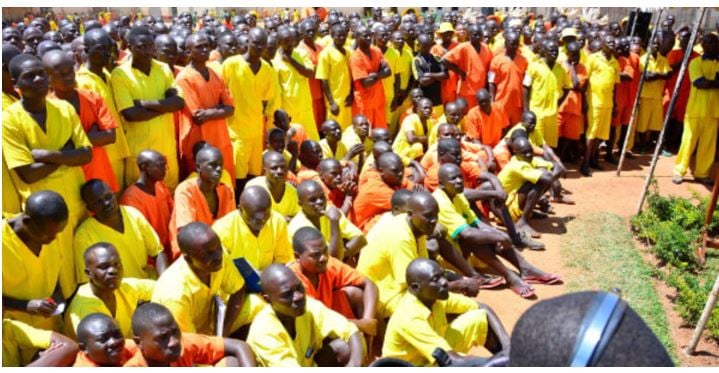

Inmates of Luzira Maximum Prison assemble for an address recently. PHOTO/FILE

What you need to know:

- Uganda has been under a moratorium on the death penalty for many years. However, with the president calling on judges to issue more death sentences, the moratorium is no guarantee that capital punishment will be abolished.

- As Gillian Nantume reports, the proponents of abolition say the death penalty is a violation of human rights and does not guarantee a reduction in violent crime.

In 1996, Maureen Nagitta* killed her husband. The couple had been married for a long time and had a number of children. Her husband had threatened to kill her, and according to her, he was intent on committing the act.

“My husband was very badly behaved. He used to beat me every night after he had taken alcohol and drugs. He was a womanizer. I did not know what to do, because my family had, in several meetings, advised him to treat me like a human being, in vain,” she says.

Nagitta is soft spoken. Her eyes are never still – they rove around the place looking for people who might be eavesdropping the conversation. Hers is a lonely life since her children and relatives abandoned her.

“When my husband died, I was arrested, tried and I was sentenced to death. Life on death row was hard. We endured menial labour, beatings, and bad feeding. Everyday, I had the constant fear that I was going to be executed anytime,” she explains.

In a 2009 landmark case, the Supreme Court of Uganda abolished the mandatory death sentence after a successful Constitutional petition filed by inmates led by Susan Kigula. The petitioners argued that the death penalty was unconstitutional and took away the right to live as given by God.

Strangely though, Dr Livingstone Sewanyana, the executive director of Foundation for Human Rights Initiative (FHRI), says following the constitutional petition, many of the petitioners were not happy with the outcome.

“We had expected them to jubilate when the court ruled that their sentences had been commuted to life imprisonment. However, they were extremely unhappy. Some were very clear that they would rather be executed because it is quick and everyone is going to die, anyway. Actually, the punishment they feared the most was life imprisonment,” he says.

Following the success of the petition, Nagitta’s sentence was commuted to life and she was eventually released in 2022 after spending 26 years in prison.

“None of my relatives, children or former friends visited me in prison. I was so lonely, with only the company of a few prisoners who cared about me. I forgot about life on the outside. Sometimes, I wondered if I would ever leave prison alive,” she says.

Nagitta’s situation is no different from that of Irene Namukasa*, who was also convicted of murder after her arrest on October 2, 1992. She was 24, with two children.

“I will not tell you who I killed, but I can confirm to you that life on death row is the greatest challenge one can face in life. You think about death all the time. Every time I saw a new prison warden, I wondered if he was the one who was going to kill me. I was always worried,” she says.

Namukasa adds that any prisoner on death row is treated differently because they are not allowed the freedom to walk around the prison like other convicts. Sometimes, they are not allowed to bask in the sun.

In 2009, Namukasa’s sentence was commuted to life imprisonment and after 23 years, she left Luzira Maximum Security Prison in October 2015.

A case for abolition

Uganda still upholds the death sentence. Article 22 (1) of the Constitution of the Republic of Uganda 1995, says, “No person shall be deprived of life intentionally except in execution of a sentence passed in a fair trial by a court of competent jurisdiction in respect of a criminal offence under the laws of Uganda and the conviction and sentence have been confirmed by the highest appellate court.”

Frank Baine, the deputy director of Corporation and Corporate Affairs/spokesperson of the Uganda Prisons Service, confirms that currently there are 70 people on death row.

“In 2009, after the constitutional petition, the numbers in the Condemned Section went to zero. However, people are still committing crimes, and the courts have been sentencing people to death,” he says.

Baine adds that today, three people are ready to be hanged and all they are waiting for is the signing of the death warrant.

“All the 70 death row inmates filed appeals in court. However, two men and one woman have completed the appeal process and the judges upheld their death sentences, saying they should hang until they die. So, for three years, we will wait for the warrant to be signed,” he explains.

The prisons’ spokesperson adds that those advocating for the abolition of the death penalty failed to convince Parliament to make an amendment in the constitution.

“Even in the Kigula case, the judges ruled that the death penalty is constitutional. However, sentencing a convict to death shall be at the discretion of the presiding judge,” Baine says.

Every October 10th, the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty and abolition actors worldwide – including FHRI – celebrate the World Day Against the Death Penalty. The day highlights the progress achieved in the global campaign for the abolition of capital punishment.

Under the theme, Security and the Death Penalty, in 2024 and 2025 the World Day will serve as an opportunity to challenge the misconception that the death penalty can make people and communities safer.

Sewanyana argues that the strong global perception that the death penalty is a deterrent to crime and that when people commit capital offenses they deserve to be punished by having them executed is wrong.

“As a consequence of that perception, the death penalty is being used as a political weapon against those, who most often, are deprived, have become victims of a justice system in which they cannot get legal representation. The death penalty, therefore, has been found to be a reactionary approach to enforcing justice,” he says.

Sewanyana stresses that no one condones the commission of crimes, particularly capital offenses. However, more emphasis should be placed on a preventive approach to punishing crime.

“This means that instead of focusing on executing people, we should try to prevent the commission of those offenses. The preventive approach means that the state invests appropriately in, and supports, the investigative systems and the judicial function, and as much as possible, the focus should be on rehabilitation,” he says.

Research has shown that countries that have abolished the death penalty have lower crime rates as compared to those that still uphold it. A December 2018 report by the Abdorrahman Boroumand Center, a Washington, DC-based organisation that promotes human rights and democracy in Iran, examined murder rates in 11 countries that have abolished capital punishment, and found that ten of those countries experienced a decline in murder rates in the decade following abolition.

“Countries that have abolished the death penalty have put more energy in ensuring that their justice systems work. Those who find themselves committing murder are subjected to life imprisonment,” Sewanyana says.

Uganda’s last executions

On April 27, 1999, 28 convicts were hanged in the Condemned Section of Luzira Maximum Security Prison. Among them was Haji Musa Sebirumbi, a former National Security Agency (NASA) agent under the Obote II government.

However, on the evening of March 25, 2002, two UPDF soldiers were sentenced to death by a field court martial chaired by the late Colonel Sula Semakula, the 3rd Division commander, in Kotido district, and executed.

Cpl James Omedio and Pte Abdallah Muhammad, attached to the B company of the UPDF’S 67th Battalion, were convicted for murdering of Rev. Fr. Michael O’Toole Declan, an Irish Catholic priest, his driver, Patrick Longoli and his cook Fidelis Longole, a few days earlier, on March 21.

The two were tied to trees, their faces covered, and shot in front of a crowd of about 1,000 spectators. The execution triggered protests in Ireland, where the death penalty was abolished.

Since 2002, Uganda has been under a moratorium on the use of the death penalty – a temporary suspension of executions depending on the will of President Yoweri Museveni. However, a moratorium is not a guarantee of abolition.

On a number of occasions, the president has called on judicial officials not to grant bail to people on trial for capital offenses. While, on the face of it, the Judiciary has largely ignored the call, nowadays, granting bail has become very restrictive due to political influence. In some cases where bail is guaranteed under the law, it is denied.

Proponents of the death penalty say an individual will be less likely to commit violent crimes if he or she knows they will face execution. However, this argument is flawed because criminals rarely anticipate the consequences of getting arrested. If an armed robber knows he faces the death penalty upon arrest, he will lose nothing by committing more murders while attempting to flee the crime scene.

“In 1999, a few days before the 28 people were executed, bombs went off at the Old Taxi Park. That goes to show you that there is no connection between execution and the commission of crime. The criminal is committing crime on account of the existing conditions he finds himself in, not because he is going to be executed,” Sewanyana says.

Fairness to families of murder victims

While the campaign against capital punishment is basically about fairness and justice, public opinion still questions how its abolition will bring about fairness to the aggrieved families of the victims.

“When your child steals food, you do not get so angry to the point that you pour all the contents of the saucepan away. That will be a loss-loss situation. Sometimes, crime is not committed intentionally. If people are given life imprisonment, they will reflect on their crimes, repent and reform,” Namukasa argues.

Of course, some crimes are premeditated, but Namusaka argues that there is no one who can resist change.

“A bad person can become a good person, and vice versa. A reformed criminal can come back into society and do wonderful things, uplifting those he finds there. If you carry out research, you may find that none of those whose cases were commuted to life in 2009 has ever gone back to prison,” she says.

The proponents of abolition say the most effective punishment for those convicted of capital offenses is life imprisonment because it gives the convict time to reflect on the consequences of their actions and reform.

“Executing someone will not restore (the life of) the victim. Secondly, it does not mean that the state gives compensation to the family of the victim, so they have nothing to gain from it, not even closure. Part of the fairness process is to provide effective punishment. Under international law, the state has an obligation to protect lives, and if it has failed to do so, it should be made to pay compensation,” Sewanyana argues.

While in most countries murder is the only crime that attracts capital punishment, in Uganda, 28 offenses attract the death penalty. These include murder, aggravated robbery, rape, aggravated defilement, treason, desertion from the army, and terrorism, among others.

Evidence has shown that some of these crimes, though, can be politically motivated.

Hostile public opinion, lack of political will

The campaign to abolish the death penalty has come up against a number of obstacles, including the rise in violent crime. Public opinion of capital punishment oscillates with the rise or fall of the crime rate.

When violent crime goes up – during situations of poverty, unemployment, and despondency as is being witnessed today – the public wants stiff punishment of offenders; when it goes down, people are keen to advocate for human rights.

In 2016 and 2022, FHRI carried out opinion polls on the abolition of the death penalty. The results of the 2016 poll, carried out in the general public, were overwhelmingly in favour of abolition, 64 percent to 36 percent. The 2020 poll carried out among the political class, showed that they were in favour of retaining the death penalty.

“Politician are, by nature, afraid of public opinion and are also mindful of the options available to them. The reason abolition of the death sentence may not be easy in Uganda is that it is seen as a legal option the Executive can rely on sometimes to deal with situations that it cannot easily contain, like in the aftermath of a violent riot,” Sewanyana says.

President Museveni has, on a number of occasions, urged judicial officials to pass the death sentence, with the latest being in February 2022, during the opening of the New Law Year. At that event, he called for a mandatory death penalty on people found guilty of raping women, murder, and those who destroy property while rioting.

Saying he does not understand life imprisonment, the president called on the officials to impose the death sentence on capital offenders and it will be up to him to decide whether the convict should be hanged or forgiven, under the presidential prerogative of mercy.

Situation in other countries

Rwanda and Burundi abolished the death penalty in 2007 and 2009, respectively. Kenya and Tanzania are operating under a United Nations moratorium, while South Sudan still upholds the death penalty.

“Rwanda and Burundi have undergone brutal civil wars and they understand that the death penalty is a weapon of vengeance. The analogy is that if you have the death penalty, there are high chances that it can be applied to you (political leader) because it is also a political weapon. It is only applied when it suits those in power. Why do you think Ssebirumbi was hanged but Chris Rwakasisi (former security minister in Obote II government) was spared?” Sewanyana asks.

For the last 20 years, the Democratic Republic of Congo has also been under a UN moratorium on executions. However, on March 13, 2024, the DRC’s Minister of Justice, Rose Mutombo, notified judicial authorities of the government’s decision to resume executions to combat treason within the army and to put an end to gang violence in Kinshasa.

On the global stage, Amnesty International believes China is the world’s leading executioner, killing thousands of people every year. 55 countries still actively have the death penalty. Of these, nine only use it for the most serious crimes such as multiple killings or war crimes, while 23 countries have been under a moratorium for 10 years.

The rationalisation for the campaign on abolition of the death penalty is that far from making society safer, it has a brutalising effect on society. Globally, the proponents of the abolition campaign believe that state sanctioned killing only serves to endorse the use of force and to continue the cycle of violence.

*Names changed to protect the identity of the source.