Prime

Njabala starts a conversation

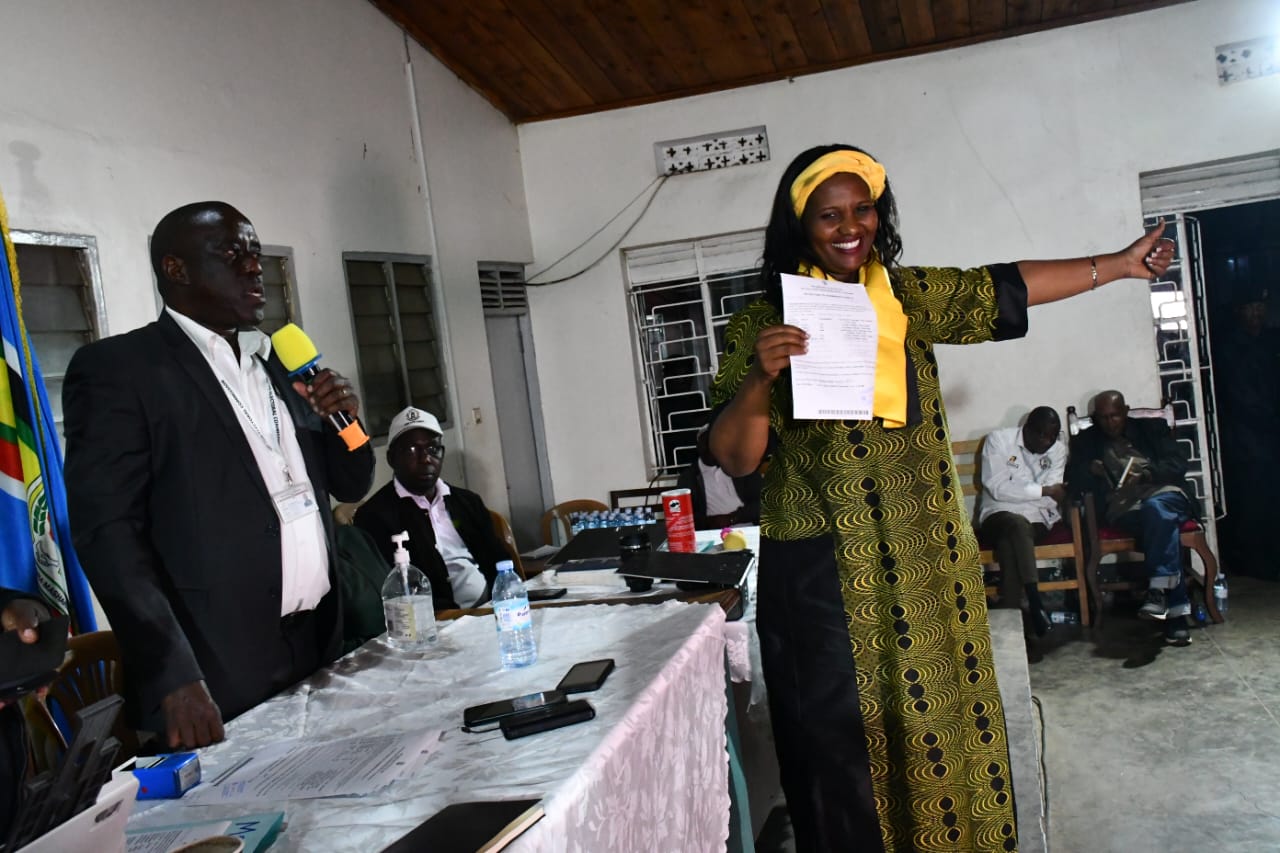

A few of the patrons examing Pamela Enyonu’s installation A Few Burning Questions.

What you need to know:

- On Women’s Day, female artists came together for the second edition of Njabala annual exhibition. This year, they tackled different societal topics.

When curator Martha Kazungu put together the 2022 Njabala This is Not How, the purpose was to examine the folklore of Njabala and her dead mother’s spirit.

In that exhibition, they opened a pandora’s box that many people agreed and disagreed with in equal measures.

Njabala This is Not How took place on March 8, 2022. This was the inaugural edition of an exhibition that is now growing into a platform for fresh talent of artists, voices, as well as a time to delve into very uncomfortable conversations.

Last Wednesday, on Women’s Day, the second edition of Njabala exhibition took place at the Makerere University Margaret Trowell Art Gallery.

Holding space

The edition aptly titled, Njabala; Holding space delved into conversations and asked important questions of whys or when. With varied themes around labour and care, this edition looks at a world that sets standards and at the same time exploits women.

But what makes the exhibition special is a fact that while looking at some of the evils, it doesn’t present a single villain, in fact, it shows us that the world; both men and women are exploiting women, directly, indirectly and some unknowingly.

With the help of artists Pamela Enyonu, the only returning artist from the inaugural edition, Kazungu, the curator was joined by Birungi Kawooya, Mable Akeu and Pepita Biraaro.

These were artists that came through an open call the Njabala Foundation made back in 2021, through the two years, they have held different sessions that later led to them bouncing off ideas that later gave birth to the works on exhibition.

Beyond the art though, the exhibition also captures the power of literature thanks to an essay by writer and spoken word artist Gloria Kiconco. Titled, Idle Hands: Notes on rest, talks about growing up in a foreign land where she was privileged and moving back to Kabale where rest wasn’t necessarily part of the day schedule.

“...I spent the school holidays in Kabale. The plan for everyday was the demands of the house. To cook, to clean, and to entertain,” she writes.

Kiconco’s essay adds context to the exhibition in different ways, from giving a literary view of the concept that is rest and in other ways paints a picture of a woman growing up in the west and the one growing up in Uganda.

The artists whose work was exhibited all tackled these themes as well, rest, care and labour.

Akeu revisits a culture that seems to be extinct, shaping the hairline (okumwa ekyenyi). The practice is not only a sign of care, but one of those moments that brought children closer to their mothers.

The art

Akeu’s medium is charcoal and coloured pencils on paper, the set of artworks capture the different stages of the process, when the mother has a connection with the daughter, face to face, from the side and also captures her emotions in a close up.

Njabala celebrates and empowers women thus, Akeu’s pictures of shaping the hairline couldn’t stay true to the process. For instance, in all the paintings, the mother wasn’t using a razor blade.

“A razorblade usually represents FGM (female genital mitilation), thus, for a work that empowers, we chose to eliminate it for its symbolism,”Akeu says.

Birungi Kawooya on the other hand presents her journal on a backcloth with a little help from banana fibres and wax pastel. From one work to the next, she uses a shield and plantain to represent her state of mind.

Her work represents many themes such as white supremacy, classism, identity and patriarchy. Having lived part of her life in the United Kingdom, she plays around with backcloth shades to represent life in the UK and Uganda differently. She mostly uses the shield to represent a time she was afraid.

Pamela Enyonu’s A Few Burning Questions installation starts conversations between parents and their daughters. The exchange, what is said and what is withheld is what sets the ball rolling.

The exhibition altogether is bold and starting conversations in the best way the artists know how. Yet, even while they are pushing for equality and the best life for any woman, they don’t seem to forget the importance of family.

Pepita Biraaro’s paintings for instance stress the importance of selfcare and having the best interests for the family.

But above all, Njabala is not only growing into an annual calendar programme that allows female artists to say what they want in a way they want to, but one that is breeding new talent in an industry that badly needs it.

[email protected]