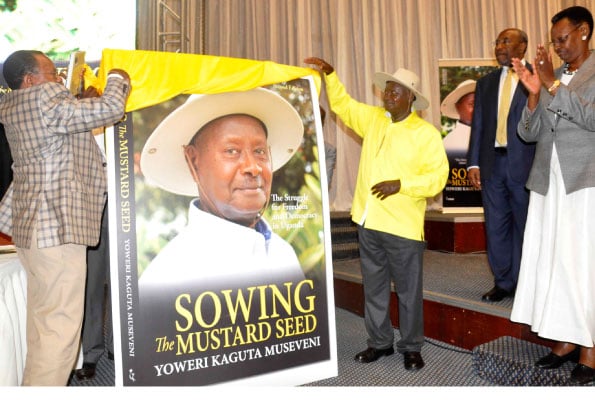

President Museveni unveils the second edition of his book, Sowing The Mustard Seed at Kampala Serena Hotel in 2016. PHOTO/FILE/STEPHEN OTAGE

Every writer’s dream is to be immortalised by their writings so that, thousands of years hence, their words are still being discussed, referenced and quoted as the wellspring of ageless truisms or witticisms.

Oscar Wilde, an Irish poet and playwright who made a name in London in the early 1890s, is arguably the most quotable author after William Shakespeare. More than 100 years after his death in November 1900, his epigrams—such as “in this world there are only two tragedies. One is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it”—still come across as fresh and original.

Every writer would love to drive their readers wild with enthusiasm to the extent that their works are enduringly Wildean. However, this goal becomes more elusive by the day. This is partly because there are very many writers in the world. Some would say too many.

According to Statista, a German online platform that specialises in data gathering and visualisation, there may be an adequate amount of writers, however. In 2023, there were close to 49,500 writers and authors working in the United States. If you include self-published authors, this figure is upwards of 2.5 million in a population of 333.3 million (as of 2022).

In the UK, there are 78,200 authors in a population of 67.8 million people. Per The Guardian, 212 million books were sold in 2021.

It is difficult to guesstimate how many Ugandan authors there are, but the number is certainly upwards of 1,000. Of this number, extremely few have resounded through the echo chamber of time. But there are Ugandan and non-Ugandan authors who have attempted such timelessness.

Accordingly, in the last 30 years, there are four books which have shaped the Ugandan psyche, for better or worse.

Emotional Intelligence

In the past, namely the 1980s and early 1990s, Ugandans were urged to be rational and not emotional. In fact, emotionalism in our deeply patriarchal society was for women and those effete men who could secretly be women. Or so we thought.

Daniel Coleman’s book—Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ—came on the market in 1995 and changed our appreciation of emotion. Suddenly, it became hip to be able to tap into your emotions in an intelligent manner.

Coleman’s preachment on emotional intelligence embraces self-awareness or understanding your emotions in order to make more informed decisions. He also wrote about how emotional intelligence led to self-regulation or the controlling of one’s impulses towards better outcomes. This meant staying calm under pressure.

The book also helped with motivation, empathy, social skills, emotional resilience or bouncing back from setbacks. Its literary prescriptions became the hymns of the Ugandan intelligentsia, which is often given to groupthink.

Sowing the Mustard Seed

In 1997, President Museveni’s memoirs enthused Uganda’s reading public. What was less known were the findings of Kenyan publishing and editorial consultant Henry Munene.

“In 1986, Kevin Shillington, an independent English scholar and author of A History of Africa, approached Ugandan guerrilla fighter Yoweri Kaguta Museveni and impressed upon the newly installed president the need to record the success of his struggle against Idi Amin and Milton Obote in a book,” revealed Munene.

He added: “Although Museveni thought it was a brilliant idea, he reckoned that he would be hard-pressed for time, what with the war going on and placing lots of demands on him. So a deal was struck. Shillington would bring a voice recorder and interview the man who would become president of Uganda and go on to stay at the helm for well over three decades. The interview was done. Ever the stickler for details, Museveni even suggested the title, Sowing the Mustard Seed. Macmillan Press Limited published the book in 1997.”

This raised the question of whether Mr Museveni wrote this book or not. Nonetheless, this is immaterial. The story is still the President’s. And it is the story that captivated the Ugandan reader most. Not the English used to tell that story.

This book was the first insider’s revelation of how Mr Museveni shot his way to power. Sure, there was Museveni’s Long March from Guerrilla to Statesman by Ondoga ori Amaza. But this represented a whimper compared to the bang Sowing the Mustard Seed made.

The Headline That Morning

In the world of poetry, Ngobi Kagayi’s The Headline That Morning and Other Poems changed the literary landscape forever. The audiobook influenced how spoken word poetry was rendered. Thanks to Kagayi, it became more iconoclastic and polemical. Young poets everywhere started copying his declamatory style of poetry.

It was nothing short of revolutionary. Kagayi became a literary celebrity spoken of in the same breath as Susan Kiguli, Julius Ochwinyo and Timothy Wangusa.

“I have made many, many friends (and ex-girlfriends) as the author of The Headline That Morning; I have received a number of favours and travel opportunities because of that book. I have been hosted on a number of literary events as an author/performer of that book,” Kagayi said in 2016 when the book was published.

The 48 Laws of Power

Robert Greene’s quasi-tome hit the bookstalls in 1998 and suddenly it was the most widely quoted book in Kampala. Commands like “never outshine the master, never put too much trust in friends, learn how to use enemies, conceal your intentions, always say less than necessary and get others to do the work for you, but always take the credit” became strictures to live by.

Thus, The 48 Laws of Power became an acknowledged guide to gaining and maintaining power, as well as understanding of the dynamics of power and influence. To say it caused a moral storm amongst the Ugandan elite is an understatement.