Male’s parent stock of cocks and mother hens maintain a huge weight without losing fertility.

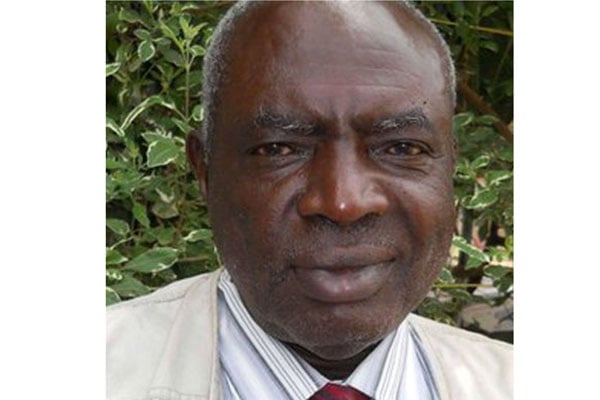

Before a friend introduced him to kuroiler chickens in 2010, Pastor Solomon Male almost quit poultry overwhelmed by perennial losses, mostly due to fraud in the industry.

Male started chicken farming in 1990 when it required Shs1300 to harvest a tray of eggs which sold at Shs2500, at a profit of Shs1200.

Raising a six-week-old broiler required Shs2000 which sold Shs3000, at a profit of Shs1000. It was good business at a time the dollar cost less than Shs1000.

But with time, that profit margin started shrinking with rising cost of production, especially due to feed costs.

The chicken breeders also connived with one another to sell poor quality chicks to unsuspecting farmers.

The biggest challenge, though, was that breeders, except Uganda Millers Limited, who produced Nuvita feeds, were also into feed manufacturing. And during dire shortages in key ingredients like mukene (silverfish), feed manufacturers could adjust the feed formulations, without the farmers’ knowledge.

“These adulterations affected chicken growth but the manufacturers always blamed it on weather changes or anything else,” Male said.

Male's incubators can churn out at least 5000 chicks every week. PHOTO/ABDUL-NASSER SSEMUGABI.

The feed adulterations also caused chicken diseases, but the farmers could not connect the dots until one bold veterinary doctor Benon Sebina launched a crusade against this fraud.

Sebina told farmers that the rampant diseases, poor growth, and poor egg production was due to adulterated feed.

He also taught farmers how to formulate their own feeds and reduce dependence on antibiotics to avoid being shortchanged by unscrupulous dealers.

Sebina and Male, who had formed Uganda Poultry Farmers Network (Upofan), engaged the Ministry of Agriculture, which sponsored their sensitising efforts.

Game changer, redeemer

Farmers incurred huge losses. Even reputable feed makers closed shop. Male too paused in 1999 but even when he resumed in 2001 things were no better.

He hung in there, until a friend introduced him to kuroilers—a dual-purpose breed which was developed in India in the early 90s to improve livelihoods in rural communities.

Kuroilers come in different shades: black, white, grey, red, brown, spotty, cream and more. Some have frizzled feathers and naked necks.

Being hybrids of different chicken breeds, kuroilers grow faster and gain meat weight faster than the indigenous breed, lays more eggs than the indigenous breed and is more resistant to disease and tough weather conditions than exotic breeds.

To Male, kuroiler business was a game changer. Like in most new ventures, the rewards weren’t instant. But the wait wasn’t too long. “I persevered until kuroilers redeemed my finances,” Male said.

“You can sell a three-month-old kuroiler at Shs20,000 or Shs25,000, with a good profit, because at that age, you may have invested Shs15,000,” Male said. “Yet selling a broiler beyond six weeks, even at Shs30,000, is a loss. But many won’t see it because they don’t keep records of what they inject in the business. That’s why many quit the business.”

The magic is that a kuroiler efficiently converts feed into tender and delicious meat and eggs. Interestingly, this feed may include agricultural, household and natural waste which is abundant, cheap and sometimes free in villages and urban areas, which gives a farmer more profits.

Value addition

A kuroiler is more than dual-purpose: meat, eggs, and chicks. Usually, by five months, Male’s cocks are sold out and the hens are also big enough for meat but he reserves some for reproduction purposes.

His backyard farm has several batches of kuroiler chicks, from day-olds to one-month-olds. They are products of a parent stock of huge cocks and hens which mate to produce fertilised eggs. Ideally, a cock caters for eight to 10 hens. It should be mature enough to fertilise but should be replaced with a younger one after six to eight months because a cock’s sexual urge and stamina reduces with age.

Male replaces his roosters with younger ones after six to eight months of mating. PHOTOs/Abdul Nasser Ssemugabi

Meanwhile, a hen should have laid for about two months to produce quality fertilised eggs, each tray sold at Shs15,000 to Shs20,000. And if well handled, a kuroiler can lay for up to two years.

Male prefers adding value to the eggs by hatching them in his incubators, which can churn out 5000 chicks every Tuesday.

He sells a day-old chick at Shs2700. He also broods some for a month, selling each at Shs8000 to Shs10,000.

But above all, Male no longer needs to buy kuroiler chicks to continue production, as those who deal in broilers and exotic layers. “I overcame that dependence syndrome,” he said with a smile.

He also opened up his incubator to clients who bring in their eggs for hatching every weekend.

In other breeds weight comes with fat, which affects fertility but Male’s parent stock maintains a huge weight without losing fertility.

He sells a kuroiler cock between Shs25,000 and Shs60,000, depending on age and purpose, while an off-layer ranges between Shs25,000 and 35,000. “Basically kuroilers can be sold at any age.”

Superior ‘eggonomics’

A kuroiler hen can lay between 150 to 200 eggs a year, depending on care. But let’s take 150. If 80 percent of those eggs hatch, Male gets 120 chicks. Each sold on day one at Shs2700, meaning every mother hen gives him Shs32,4000 a year. No other breed gives you this much, moreover at a cheaper cost.

The Rhode Island Red, the commonest commercial layer breed in Uganda, lays between 200 and 300 eggs a year. Let’s take 300. Each egg sold at Shs300 (farm price), means each bird gives you Shs90,000 per year, which is over 50 percent less than a kuroiler yields.

The indigenous hen, aka local, comes close to the kuroiler because of its ability to lay fertilised eggs but comes short for its lower laying capacity. It might give you only 100 eggs, of which 80 might hatch. Each day-old chick sold at Shs3500, means Shs280,000 per hen per year.

Meat is all broilers can offer. So if a farmer rears 12 broiler batches in year—that is a batch every month, which is quite rare—12 broilers, each sold at Shs13,000, yield Shs156,000 a year.

Shock absorbers

A decrease in the diet quality or quantity can make a broiler lose weight or a layer drop in production. Worse still, they get sick. And once productivity drops, Male said, it may be hard to regain it. But kuroilers are not as delicate. They absorb shocks better, adjust to changes easily, without much decline.

Being good scavengers, kuroilers can also thrive in free-range conditions, because they can forage for grass, bugs, herbs, and anything, which lowers feeding costs and bolsters flock immunity.

This is how healthy kuroilers chicks look like at four weeks.

Beware of crooks, misconceptions

Male warns farmers against crooks in the market. “Many use confusing terminologies like F1, F2 to dupe ignorant clients,” Male said.

In genetics, the P1 generation are the parents, the F1 generation are the offspring of those parents, and the F2 generation are the offspring if the F1 generation members are mated with one another.

The F1 generation is deemed a better breed: stronger immunity, better growth and performance than the F2. But the truth is no farmer is meticulous enough to tell if a particular batch of chicks is F1 or F2 or F3. Likewise, there’s little a breeder or supplier can give to prove which generation particular chicks belong to.

“Those who tell you they’re selling F1 kuroilers may be selling crossbreeds.”

Kuroilers can easily be mistaken with other dual-purpose breeds like Sasso and Rainbow. So you need a genuine supplier. Besides his hatchery, Male recommended NAGRC&DB—The National Animal Genetic Resources Centre and Data Bank in Entebbe—as one of the reliable suppliers of genuine kuroiler chicks.

Male also warns against costly misconceptions. For instance, beliefs that kuroilers can eat anything and are more resistant to diseases has caused farmers losses as many tend to neglect vaccination and proper treatment. “Yet kuroilers too need nutritious feeding, proper hygiene, ventilation and biosafety for maximum productivity.”

Key fact

A decrease in the diet quality or quantity can make a broiler lose weight or a layer drop in production. Worse still, they get sick. And once productivity drops, Male said, it may be hard to regain it. But kuroilers are not as delicate. They absorb shocks better, adjust to changes easily, without much decline.