Prime

Could public health financing relieve the challenges of Universal Health Coverage?

What you need to know:

- The budget estimates indicate a continued reliance on external funding, which raises questions about the criteria for choosing and allocating resources to priority areas. This comes amid recent pronouncements by politicians and government officials that the country is taking charge of the health of its population by increasing public financing.

For the next financial year, more than half of the funds needed for 11 priority areas in the health sub-programme are expected to come from development partners, indicating a high level of donor dependence.

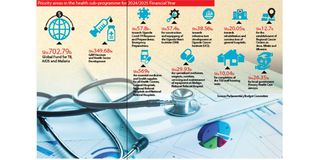

According to the budget estimates for the 2024/2025 Financial Year analysed by the Daily Monitor, out of the Shs1.87t allocated for the 11 priority areas, Shs1.05t will be provided by the Global Fund and Global Vaccine Alliance (Gavi).

According to details captured in the report of the Budget Committee of Parliament on the Annual Budget Estimates for the 2024/2025 Financial Year, the global fund will provide “Shs702.7b for fighting against tuberculosis, Aids, and malaria. Gavi will also provide Shs349.68b for vaccines and health sector development.

The report indicates that Shs57.8b out of Shs1.87t will be allocated for implementing the Uganda Covid-19 Response and Preparedness; Emergency Preparedness. This allocation has faced criticism from some members of the public who argue that Covid-19 is no longer a serious threat to the nation.

Additionally, another Shs57.4b will be used for the construction and equipping of the Uganda Heart Institute (UHI) in Naguru, Kampala.

Other priority areas include infrastructure development at the Uganda Cancer Institute, rehabilitation and construction of general hospitals, and establishment of regional cancer centres in Arua, Mbale and Mbarara districts.

At least Shs590b of the 1.87t will be spent on essential and specialised medicines, and health supplies for hospitals, while Shs26.35b will be given to local government primary health care services.

The budget estimates indicate a continued reliance on external funding, which raises questions about the criteria for choosing and allocating resources to priority areas. This comes amid recent pronouncements by politicians and government officials that the country was taking charge of the health of its population by increasing public financing.

No money for organ transplant progress

Members of Parliament also noted in the Health Committee report, that among the unfunded priorities, understaffing has rendered facilities such as Intensive Care Units (ICU), which the government spent a lot of money to establish, non-functional.

Dr Rosemary Byanyima, the executive director of Mulago National Referral Hospital, says only 14 out of the 27 ICU beds are functional due to inadequate human resources.

“We need to recruit more personnel. If you have only two people (specialists per unit) then you cannot run the facility with only one [specialist] when the other goes for training or is on leave,” she says.

The legislators also note that whereas at least Shs827b was required by the National Medical Stores (NMS) to buy drugs and other health supplies for hospitals, only Shs569b was provided. This left a gap of Shs232b, with the most affected health facilities being regional referral hospitals, general hospitals, and Health Centres II and III.

Organ transplant council

The other unfunded priority, which the committee highlighted, was the Shs5b for establishing the Organ Transplant Council, launched last December with one person undergoing a successful kidney transplant at Mulago National Referral Hospital.

The Ministry of Health (MoH) had halted the activities awaiting funding to establish the council even as Mulago Hospital reported that many patients with end-stage kidney disease and in need of urgent transplants were waiting for the life-saving surgery.

“No more was allocated for organ transplant. It was an unfunded priority. There is a strong need for the government to increase its funding because of the reality of donor fatigue. As the demand for health services increases amid competing priorities and a shrinking global fiscal space, there is a need for novel domestic health financing mechanisms.

There are issues to do with supplies for specialised services and we are trying our best to increase funding for such services and Mulago Hospital as a whole,” Dr Charles Ayume, the health committee chairperson, tells this publication.

Priority

Dr Jane Ruth Aceng, the Minister of Health, on the other hand, says the country needs to elevate health as a priority investment area for the government.

“No nation can develop when it has not invested in the health of its people. Uganda is still facing challenges in implementing interventions aimed at attaining Universal Health Coverage (UHC). Recently, at the United Nations, Uganda, as many other countries, made commitments. One of them is strengthening community-led interventions through programmes that build the capacity of the community health workforce, who include community health extension workers and village health teams, among others. These people matter. All events start in the community and they end in the community, even if it is high blood pressure. So, we need to strengthen the capacity of these people so that they can support us,” Dr Aceng says.

She also calls on the government to implement programmes that address social determinants of health at all levels, such as water and sanitation, food security, education, safe transport and housing.

“These affect our quest to move to UHC, where all people have access to the full range of quality health services they need, when and where they need them, without financial hardship. Some of our health facilities do not even have water up to now. They harvest rainwater or use water from boreholes, yet the country is one of the most endowed countries in terms of safe water. Sometimes, even National Water and Sewerage Cooperation runs out of water, why?” the Minister asks.

Reach

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) rankings, Uganda’s UHC Index of service coverage stands at 49 percent, which is an improvement from 22 percent in 2000. But this is still below the global average of 68 percent.

“Right now, according to the Uganda Demographic and Health Survey (UDHS), everyone is within five kilometres reach of a health facility because of increased government investment but the goal is to be within a four kilometres reach of a facility,” Dr Aceng reveals.

Although some politicians have claimed that the money for the Covid-19 response was misused, Dr Ayume says there is evidence that the money given to the health sector has been put to good use.

“The results are evident. We have halved maternal mortality from 336 [deaths per 100,000 deliveries] to 189 [deaths per 100,000 deliveries]. That is one of the best rates in the region. Last year, in December, we had our maiden kidney transplant. Money has been put to good use,” he defends.

Dr Aceng also says the sector is increasing efforts to ensure the quality of care improves.

“There is a need to increase investment in health infrastructure, medical products, technology and digitised health information. All these are ongoing. We also need to build the capacity of health workers in terms of numbers, skills and capacity on research and development while keeping them motivated and ensure retention. Financial risk protection should be addressed through the introduction of the National Health Insurance Scheme to protect households from catastrophic health expenditure,” she adds.

Efficient resource use

Dr Yonas Tegegn Woldemariam, the WHO country representative, says to attain UHC, the country should become more efficient in resource utilisation.

“Having one national plan, one budget, and one monitoring and evaluation framework, which is implemented based on a whole-of-society approach, will go a long way in addressing fragmentation, duplication, and misalignment challenges. Health taxes should be seen as a public health intervention to deter the consumption of unhealthy products. This will prevent future health costs, especially for non-communicable diseases. WHO will continue working with the Ministry of Health and partners, offering technical expertise, knowledge, and global best practices to ensure Uganda's health financing system is robust, adaptive, sustainable, resilient, and high-performing," he says.

Minimum health package

According to the 2023 Health Financing Progress Matrix assessment report for Uganda by the MoH and the WHO, the contribution of the government (public funds) to total health expenditure between 2009 and 2020, rotated between 14 percent and 17 percent.

In 2020, specifically, up to 41 percent of the cost of healthcare delivery was met by development partners (external funders), 42 percent for private (including out-of-pocket expenditure and private insurance) sources and 17 percent from the public (government).

“External funding and private sector financing, especially from out-of-pocket, still contribute the largest share of Total Health Expenditure (THE). Public expenditure as a proportion of THE is about 17 percent, which is very low. The health sector allocation as a proportion of total budget allocations for the 2022/2023 Financial Year is six percent and has for a long time oscillated between five percent and nine percent, which is significantly below the 15 percent Abuja target,” the assessment report reads.

“The Out-Of-Pocket (OOP) expenditure is still very high, which undermines the capacity of households to access healthcare and contributes to catastrophic expenditures and impoverishment. The limited public expenditure on health means that there is a high reliance on external funding and OOP which have challenges of unreliability, un-sustainability, and inequity, particularly for OOP,” the report reads further.

Daniele Nyirandutiye, the mission director in Uganda of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), says there are strategies the country can use to reduce patient costs.

“One of the biggest challenges in different communities in Uganda is the transport costs, which makes it hard for people to reach health facilities to access healthcare. One of the things that we have done in partnership with Uganda is to institutionalise the community health approach – bringing services closer to communities and making sure the community health workers are trained and equipped with tools and products because we want to promote prevention.

She adds that the goal is to make sure households are quickly able to identify a fever and go to the health facility early.

“What we see is that people arrive late and this increases the cost of care. If you look at the recent DHS report, there is a reduction in maternal mortality because access to information has improved and mothers are arriving early in hospitals because they can tell the signs,” she says.

The case study of the Uganda National Minimum Healthcare Package (UNMHCP) by Isaac Kadowa of the Regional Network for Equity in Health in East and Southern Africa (EQUINET) shows that the government has also been falling short of its targets.

“The per capita public expenditure on health from the financial year 2010/11 to 2015/2016 has averaged around $11 (Shs41,800), the highest amount was $13.5 (Shs51,300) in 2014/15 and the lowest was $9 (Shs34,200) in 2012/13, a fluctuating trend. Public sector health funding has thus remained below the earlier target of $28 (Shs106,400) per capita estimated as the amount required for the provision of the UNMHCP,” the report reads.

Non-communicable diseases

The authors of the Health Financing Progress Matrix assessment report say whereas the government introduced fiscal measures that create incentives for healthier behaviour by individuals and firms, the impact on public health is not known.

One of the measures highlighted by the authors was the government “heavily taxing products that undermine healthy life and are associated with Non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as alcohol and tobacco. The main objective for the government has been to raise enough revenue given that these products are by nature ‘price’ insensitive, which creates an opportunity to tax them more and to reduce the consumption of unhealthy products. However, there seems to be no direct link between taxes, prices, and demand (apart from the theoretical understanding). So it’s not conclusive whether these taxes are indeed incentives for certain healthy behaviour.”

Dr Charles Oyoo Akiya, the commissioner for NCDs Control at the Ministry of Health, says there is a need for a multi-disciplinary and multi-sectorial approach to combat NCDs such as cancer and heart disease, which are on the rise.

“The issues start elsewhere and come to us in the Health Ministry to handle. We need to address the root causes. If we put the little resources in the country to good use, we can do more. There are issues around medicines, equipment and human resources gaps. As a Ministry, we are aware of those constraints. We are advocating for increased resources to address NCDs, as we are leaning more towards communicable (infectious) diseases,” he adds.

Dr Nicholas Kamara, the chairman Parliamentary Forum on NCDs, says there is a need to bridge the gap between experts and communities to sensitise the population about the prevention of NCDs.

“We have also pushed for integration of NCDs in HIV care. You treat someone with HIV and they end up dying of NCDS such as diabetes. We are proposing an increase in the budget for NCDs. It is money that made HIV a big issue and the care is robust. We need to put money towards the treatment of NCDs. Giving money to the Uganda Cancer Institute and Uganda Heart Institute and assuming enough has been done towards the treatment of NCDS is misguided. There is nothing [given] for prevention,” he adds.