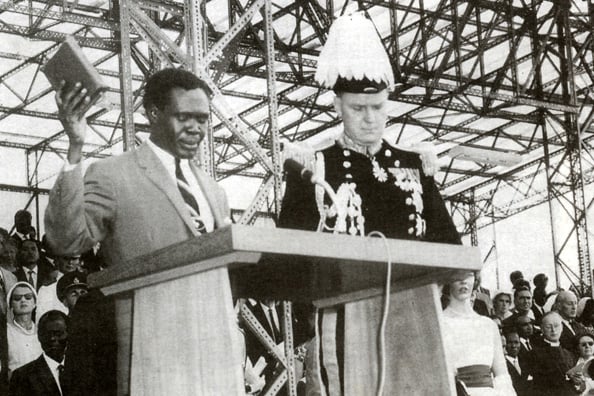

Prime

Is Uganda better off than in 1962?

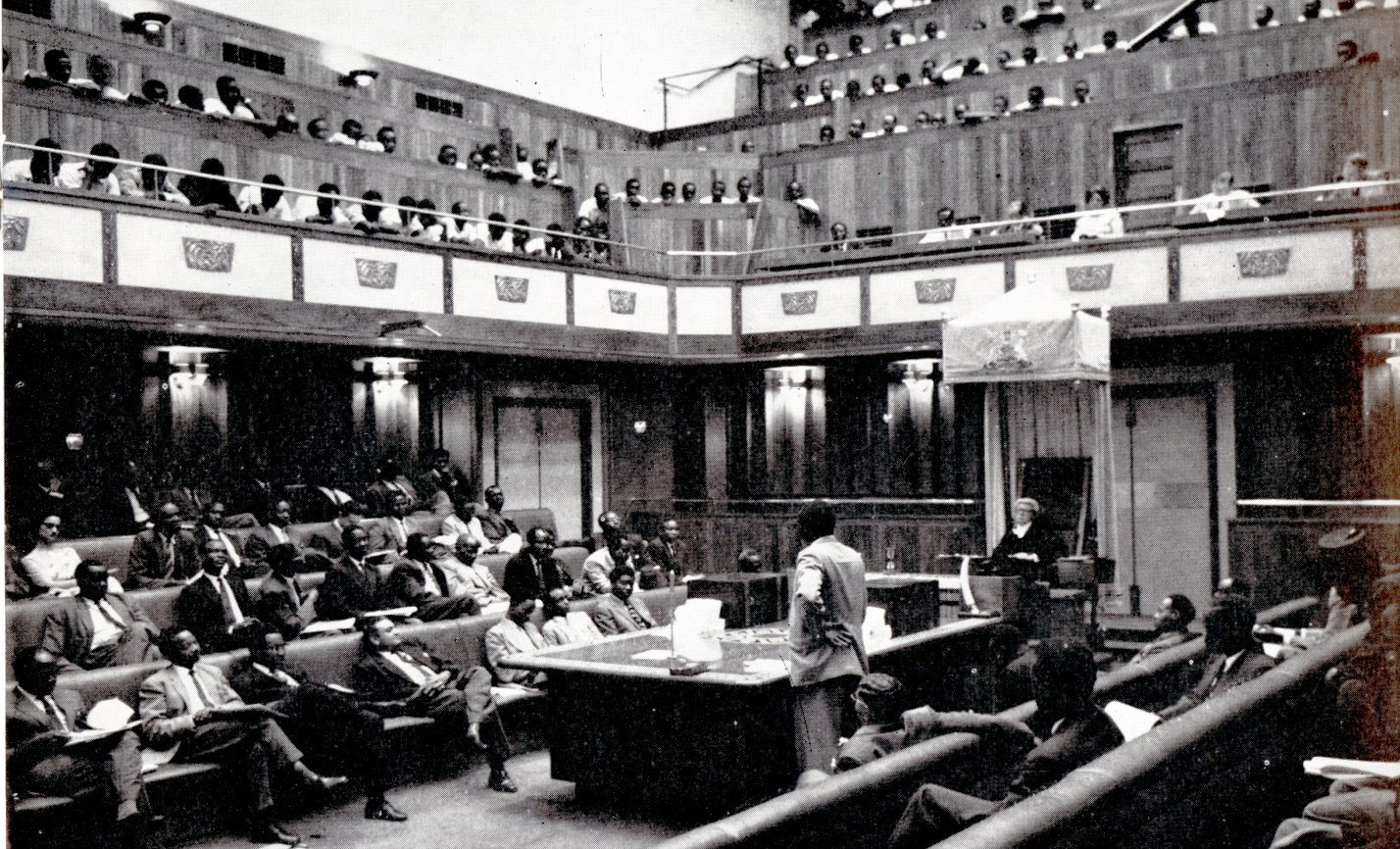

Parliament of Uganda at independence. PHOTO/FILE

What you need to know:

- In the 1950s, Uganda was the Commonwealth’s largest producer of coffee and the largest producer of cotton among the British colonies, before coffee overtook cotton as Uganda’s main export earner starting about 1958.

Continuing with the theme of independence 61 years ago, a natural question to ask is: Is Uganda better off today than it was in 1962?

This is a long-winded question and much of the answer comes down to what we see or want to see.

Let’s start with the standard of education, which most would agree is one of the best ways of gauging a country’s health.

The CIA World Factbook in an entry on Uganda updated on October 3 states: “Uganda gained independence in 1962 with one of the more developed economies and one of the strongest education systems in sub-Saharan Africa, but it descended within a few years into political turmoil and internal conflict that lasted more than two decades.”

Separately, the National Resistance Movement (NRM) historical and former Inspector General of Government, Augustine Ruzindana, stated this in a post on the social media platform Twitter (now X) on October 9: “I was in S2 in 1962. For students not much change, we followed same Cambridge syllabus, with mainly White teachers. At HSC everyone was sponsored by Local Govt, at university by Central Govt. No graduates were unemployed. Govt was still effective until 1971 coup, then downhill.”

HSC means Higher School Certificate and generally meant A-Level. Most older Ugandans, especially the generation that had come of age by the time of independence, speak fondly of their time in school, under the tutelage of British and American teachers.

Journalist Andrew Mwenda once told this writer of being struck, during conversations with former presidents Milton Obote (Uganda), Kenneth Kaunda (Zambia), and Frederick Chiluba (Zambia), their formative years in British-run secondary schools stood out as among the best years of their lives.

Turning to the economy and taking Africa as a whole, in 1948, Africa accounted for about 7.3 percent of all global exports.

In 1953, that figure had dropped to 6.5 percent. In 1963, it was down to 5.7 percent. In 1973, Africa’s share of global exports was at 4.8 percent.

By 1983, it was at 4.5 percent, in 1993 it was at 2.5 percent, and today in 2023, the figure is at 3 percent.

In last Sunday Monitor’s article, I noted the fact that of the 34 sub-Saharan African countries that participated in the US Agoa trade arrangement, only four (Botswana, Nigeria, South Africa, and Angola) had met their quotas by May 2015.

Africa’s steady decline in the share of global exports since 1948 shows a structural weakness that can only suggest that the continent was its strongest during the colonial era.

The slight uptick in exports from the 2.5 percent global share of 1993 to the current 3 percent has mainly been due to China’s rapid economic growth and its insatiable need for commodities, many like petroleum, gold, coffee, natural gas, and cocoa are produced by Africa.

Incidentally, the last year that Uganda had a favourable balance of payments, that is, exporting more than it imported, was 1980.

In every year since then, despite GDP growth, Uganda has continued to import more than it exports, hence its heavy dependence on foreign aid and donor support.

In the 1950s, Uganda was the Commonwealth’s largest producer of coffee and the largest producer of cotton among the British colonies, before coffee overtook cotton as Uganda’s main export earner starting about 1958.

According to the International Monetary Fund, Uganda’s GDP per capita this year stands at $1,160 (Shs4.3m).

The country’s GDP per capita was at $62 in 1963. In 2023 money, adjusted for inflation, that is about $630 (Shs2.3m).

The GDP per capita was $237 in 1977, which is equal to $1,209 (Shs4.5m) in 2023 money value.

This GDP per capita shows the interesting difference between perception and reality.

By most accounts, 1977 saw Uganda hit its lowest point under the government of Idi Amin, and yet that year saw the per capita GDP reach the highest level of all-time.

This was partly due to the severe frost that hit Brazil that year, sending up the value of Uganda’s coffee exports, and from this coffee bumper earning the government imported fleets of Honda Civic, Honda Accord, and Datsun 120Y cars for senior civil servants for purchase at a discount.

In terms of health services, a committee headed by Prof Alastair Frazer in 1955 recommended that free medical treatment at government hospitals be discontinued and a charge of Shs1 be introduced.

This was to reduce the burden on the Treasury’s subsidies for healthcare.

By 1953, there were 227 government-run medical units in the country.

The fact that treatment at government hospitals was free of charge during the 1950s made a significant difference for families.

Free medical treatment coupled with the free A-Level education mentioned by Ruzindana, meant families lived a much more relaxed life than today.

In other words, with today’s GDP per capital at $1,160, much of that is used up in school fees and medical bills, which might explain the high levels of anxiety and frustration today when the shops are full of basic consumer goods and everyone seems to own a phone.

Limited space does not permit a full exploration of this topic.

There is a whole economic ecosystem, for instance, that has never been appreciated and given adequate treatment.

This was the network of steamer ships, trains, ports, and docks that spanned the area between Lake Kyoga, Lake Albert, and the Albert Nile during the first 60 years of the colonial era.

From Port Butiaba to Namasagali, Port Masindi to Pakwach, this system of moving cotton and other exports to Sudan and the Indian Ocean played a key role in the economic development of Teso, Busoga, Lango, West Nile, and Acholi sub-regions.

All that’s left today of this River Nile, Lake Kyoga, and Lake Victoria transportation hub is rusty dockside cranes, crumbling railway quarters (some of which in 1968 formed a new school called Namasagali College), and railway lines long lost to elephant grass.

Unsurprisingly, the closure in 1962 of this lake, rail, and river transport network in the central and north-western heart of Uganda, led to a corresponding decline in the economic fortunes of Lango, Bunyoro, Acholi, Busoga, and West Nile.

What would this part of Uganda be like today if this river and lake transport network had not been shut down and lost to history?