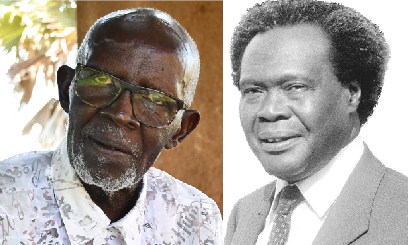

Retired Col Tonny Otoa (L) and former President Milton Obote. PHOTO|TOBBIAS JOLLY OWINY/ FILE

In the 1979 war, the UNLA (Uganda National Liberation Army), with the backing of the Tanzanian forces, while advancing into Uganda against Idi Amin forces, met tough resistance at Mutukula on the border of Uganda and Tanzania.

The fiercest battle against Amin forces was the encounter at Lukaya. It was a tough battle because Libya had sent some forces with weapons to fight in support of Amin. He had a very good air force, but on the ground, he was weak. The weakness was that he made the soldiers too comfortable and wealthy, and that finished him because the soldiers did not concentrate. But the Libyans were a force to be reckoned with.

The Lukaya battle became so intense that the Tanzanian forces contemplated withdrawing since they intended to destroy Mbarara and Masaka as revenge against Amin’s attack in Tanzania.

Tanzania’s withdrawal meant that Amin’s forces, backed by the Libyans, would easily annihilate us. So, David Oyite-Ojok brought together battalion and company commanders in the night in a high command meeting led by Gen David Musunguri of Tanzania.

Oyite-Ojok told us one thing: ‘There is no going back; all of us will die here, but we don’t want to die like cowards. We will fight.’

The following day, Milton Obote appealed to Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere to fight on since he was convincing China and Russia to help.

Once Obote succeeded in overthrowing Amin in April 1979 and formed a government after the 1980 elections, there was a lot of Tanzanian interest in seeing that Obote stayed in power.

Genesis of problems

However, Obote quickly felt so powerful and independent that he soon ignored Tanzania and their interests.

Obote also knew at the time that Yoweri Museveni’s guerrilla movement was gaining ground. The economy was in shambles, and politics was taking a toll on him, which drained his strength so rapidly that dislodging us for a second time was an easy task for the enemy forces.

The biggest mistake that Obote made was to quickly organise the 1980 elections immediately after overthrowing Amin.

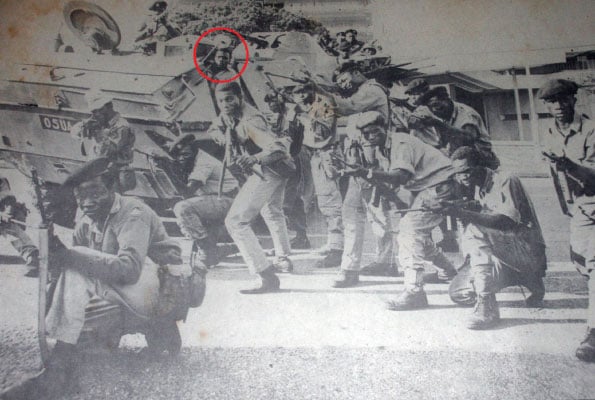

Soldiers stand guard near Radio Uganda moments before news of the military takeover was announced on January 25, 1971. Circled is Corporal Moses Galla who rammed an APC into the armoury where mutineers got guns. PHOTO COURTESY OF FAUSTIN MUGABE

The Military Council had recommended that the Amin government be replaced by a military government and we advised Obote against that move to organise elections. But he would not listen to us.

In 1980, there was a near-famine where almost all hotels across Kampala went without food. When production resumed and things were normalising in 1982, we started encountering the NRA rebellion. While the Karimojong were on the one end terrorising the north with their guns, Museveni and his NRA rebels were doing the same in the Luweero area. Signs that Obote’s government could be toppled were already being felt by 1982 since the prevailing conditions required a sober military leader like David Oyite-Ojok.

Approaching Oyite-Ojok

One morning we approached Oyite-Ojok and convinced him to declare a military rule. A Major in the army, an engineer and myself went to Oyite-Ojok (then army Chief of Staff) at Nile Mansion, where he lived.

Left to right: Members of the Military Commission Maj Zed Maruru, Mr Yoweri Museveni, Mr Paulo Muwanga, Maj Gen Tito Okello and Lt Col Oyite-Ojok. PHOTOS/ FILE

We told him that if he didn’t do anything, the government would be overthrown and our Acholi brothers would support that because they were now working with Museveni.

‘Declare military rule. We will find support around East Africa. Nyerere and Daniel arap Moi [of Kenya] will support you,’ we told him. The previous evening, the three of us sat and discussed how the government was likely going to be toppled.

Oyite-Ojok kept silent for about 10 minutes, breathed deeply and asked us what his Langi people would say if he overthrew Obote’s government.

We told him they would say nothing because the plan was to pick Obote and take him to his home in Lira where he could be confined for two to three years. He would have all the required protection, including his secretaries and other privileges.

We would look after him so that when the military restores order, he could reorganise his party and resume the presidency. Fortunately, Oyite-Ojok accepted the plot. Unfortunately, he died in a plane crash in 1983 before the coup could materialise.

Friction in the army

A deliberate delay by Obote to promote new elite military officers and retire the ageing senior officers who were troubling him led to his eventual downfall.

Tito Okello Lutua was about 75 years old, and Bazilio Okello was in his early 60s. We expected him to relieve these aged officers, give them their full packages and let them go home so that the young and more educated officers take charge of the army.

For example, Maj Gen Samuel Nanyumba and Col Zeddy Maruru were there, and then we had other people like Maj Oketcho. These were some of the able officers who would have taken over the army leadership.

But the death of Oyite-Ojok made a bad situation worse. Obote’s government practically rested on the shoulders of Oyite-Ojok for the three years preceding his death. Once he died, top army leadership knew they would soon flee back into exile.

After his demise, people, including former archbishop Yonah Okoth, kept reminding Obote to quickly appoint a chief of staff, but it took more than one year for him to appoint Brig Smith Opon Acak, an appointment that turned out to be a grave mistake.

Archbishop Okoth and his team had met Obote and told him to promote Maj Oketcho and appoint him the new chief of staff since he was experienced and well-educated and went to the UK for training.

Opon Acak’s appointment validated the conspiracy the Acholi had against the Langi that Obote’s government was tribal. They said he continuously ring-fence key military positions for Langi officers.

Opon Acak was a very efficient soldier, and on the battlefront everyone liked to work under his command since he would do intelligence and reconnaissance himself and come back and fight. But he had one weakness. Alcohol.

He was the most senior and well-trained tank engineer. He trained for seven years in Greece in tank engineering, but he was zero in administration and became a beast when drunk.

By the time Museveni was putting pressure on us with his rebellion, the West had started believing him and his words.

Our intelligence report said Museveni’s people once came to the Namugongo Shrine near Kampala and attacked people. Although Museveni’s soldiers fled the scene, UNLA soldiers rushed to the scene and indiscriminately shot and killed many people.

Once Emmanuel Cardinal Nsubuga came to Opon Acak’s residence in Mbuya (barracks) to establish what happened at about 10am the following day, he joked about the incident and teased the Cardinal.

An already-drunk chief of staff asked the Cardinal to explain how simple it was to sieve sim sim from sand particles if they accidentally mix up. Cardinal Nsubuga left disappointed.

Humiliating exile

A week before his overthrow, Obote summoned the Military Council to the Nile Mansions (now Kampala Serena Hotel) and asked what the problem was.

However, nobody responded to him because the rumour was rife of an imminent overthrow. The army was divided and disappointed due to bad leadership and poor living conditions. Worst of all, soldiers were dying in Luweero.

Worst was that some of our soldiers instead of going to concentrate at the battlefront, had diverted to looting iron sheets, coffee in cooperative stores, livestock, and raping women.

That made the communities in Luweero switch their support to the rebels.

Gen Tito Okello Lutwa swears in as president in Kampala in July 1985. PHOTOS/ FILE

On July 27, 1985, Gen Tito Okello Lutwa and Gen Bazilio Olara Okello brought the curtain down on the Obote II regime.

Fleeing to exile

In our second leg of exile, Nyerere did not want to hear about Obote following their fallout. This forced Obote to consider Kenya.

In Kenya, president Moi welcomed Obote and our team of about 45 people. We were offered residence in a decent upscale hotel in Nairobi for nearly a fortnight.

However, hell broke loose. Moi called us to his office and he told us how he wanted us to join Museveni. Opon Acak spoke on our behalf and responded that we needed to go back and consult with Obote. We went and reported to Obote about Moi’s plan.

Obote told us that we didn’t know Museveni that well because he would kill all of us. So, Opon Acak returned and told Moi that we had declined to join Museveni.

Following that meeting, it didn’t take more than five hours for Moi to organise the army, immigration, etc. to quickly mobilise transport for us and throw us out of the country.

President Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia sent two planes that took us to Zambia. For nearly two months, Zambia looked after us very well, but due to politics, it didn’t last long. We had to be handed over to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and we were transferred from Lusaka to Kafue Town, 50km out of Lusaka towards Zimbabwe.

Who is Otoa?

Mr Otoa, now 84, a retired Colonel in the UNLA, was one of the senior military commanders under Kikosi Maalum who formed the anti-Idi Amin force in Tanzania.

The former ammunition technician says his role was key in rallying the youth, the core of the UNLA, between mid-1979 and early 1986.

Otoa, who, in both Obote 1 and Obote II governments, was one of the closest army officers and advisors on military affairs to Obote, also served as the UNLA’s commander of the Central Ordinance Depot, then based at Magamaga in Jinja.