Prime

Tracing the final journey of Archbishop Janani Luwum

Man of faith. Archbishop Janani Luwum. FILE PHOTO

What you need to know:

- St Janani Luwum is one of the recognised ten martyrs of the 20th century. The saint was murdered by Ugandan president Idi Amin in 1977. His murder was a wake-up call for the international community about the inhuman regime in Uganda, writes Olara Otunnu.

On the night of February 16, 1977, a great dark deed was committed in Kampala. Archbishop Janani Luwum was murdered, at Nakasero, by Ugandan president Idi Amin. Archbishop Janani was the head of the Anglican ecclesiastical province, then composed of four countries (Burundi, Eastern Congo, Rwanda and Uganda).

The ugly showdown, unto-death, unfolded in remarkably poignant instalments, as if choreographed. These landmarks have become the Stations of the Cross (milestones in the path of bearing the Cross) in this martyrdom journey.

Showdown at Namirembe

The final journey began at Namirembe (the mother of peace), this iconic hill, majestically perched atop Kampala, with a commanding view of the city. The journey ended at Wigweng (the summit of rocks) in Mucwini Chua, in Kitgum District.

In the dead of night on February 5, soldiers stormed the Archbishop’s residence at Namirembe. For over two hours, they assaulted and abused the Archbishop and his family, as they ransacked the place. They claimed to be looking for hidden weapons. Nothing was found. In response, all Bishops assembled at Namirembe and wrote a letter to Idi Amin on February 8.

On February 14, Amin sent a cabinet minister to collect the Archbishop from Namirembe, and take him to State House, Entebbe. The Entebbe meeting was a very ugly and unsettling encounter. Amin was very hostile. He berated and insulted the Archbishop at length, before eventually releasing him to be returned to Namirembe. The Archbishop would later say, “I think I was marked to be killed on Monday at Entebbe.” He believed that it was the unexpected presence of his wife, Mama Mary, that prompted a sudden change of plan. Against his plea, she had absolutely insisted on accompanying him. As the showdown was turning ominous by the day, relatives and friends implored the Archbishop to leave the country.

Various embassies and outside churches offered to safely get him out. He understood their concerns and was very grateful, but his response was always the same, “If I, the Shepard, flee, what will happen to the sheep?” He had all the opportunities to leave, but elected to stay.

On February 15, the Archbishop and all the Bishops (and senior public servants) were summoned , through Radio Uganda, to report the following morning to Nile Mansions (today’s Kampala Serena Hotel), for a “very important event”. Early morning of February 16, the Archbishop left Namirembe to report to Nile Mansions as required.

So, the first phase of the final showdown unfolds from the night of February 5 to the morning of February 16 at Namirembe. Namirembe then is the first Station of the Cross in this martyrdom journey.

Show trial at Nile Mansions

The advertised “very important event” at Nile Mansions turned out to be an ostentatious and crude show trial of the Archbishop, cynically staged by Amin and his henchmen. The trumped-up charge was attempting to overthrow the Amin regime. At the end of the long sham trial, Vice-President Mustafa Adrisi turned to the gathering and asked, “What shall we do with these traitors?” The assembled soldiers roared back:

“Kill them!” The question was asked three times, and each time the answer was the same. A group of soldiers then stepped forward and separated the Archbishop from the other Bishops. Some Bishops wanted to accompany him, but the soldiers insisted, “His Excellency wants to see him alone.”

As he was being led away, the Archbishop turned to his fellow Bishops, smiling gently, and said, “I am not afraid. In all this, I see the hand of God.” This was the last time he was seen in public. He was taken inside Nile Mansions, where Idi Amin was waiting for him. The physical abuse and humiliation started there. Nile Mansions is the second Station of the Cross.

Later that afternoon, at about 4pm, the Archbishop was delivered, now as a battered and abused prisoner, to the headquarters of the State Research Bureau (the regime’s much-dreaded secret police outfit) in Nakasero. He was taken to dungeon Cell No. 1, located in the basement of the building.

Amin and the dark deed

At night, Idi Amin himself suddenly arrived at the premises, accompanied by a select entourage, including close associates Bob Astles and Lt Col Jumba Masigazi. The Archbishop was taken from his cell to the first-floor office of Farouk Minawa, where Amin and the team were waiting. It was in this office that Amin committed the dark deed. After taunting and savaging him for some time, Amin then shot the Archbishop at about 9pm.

The Archbishop was actually murdered at a spot (Minawa’s office) directly overlooking the compound of his own cathedral, All Saints, some 100 meters away. This building then is the third Station of the Cross. Murdered alongside the Archbishop that night were two cabinet ministers, Oboth Ofumbi and Erinayo Oryema. The latter, incidentally, had been the Archbishop’s primary school teacher in Kitgum.

The morning of February 17, a government statement was put out, narrating the official lie that the Archbishop and the two ministers had died in a car accident. While Church leaders and the family were waiting to bury the Archbishop at Namirembe, soldiers were already on their way, secretly transporting the body to the north.

The military contingent reached Mucwini in Chua Kitgum District (the ancestral home of the Archbishop) in the evening of February 17; it was already dark. Nervous and afraid for their own safety, they decided to quietly drive past Mucwini, continuing to Bana Bana military barracks in Madi-Opei, some 24 kilometres north. Here they spent the night. This is the fourth Station of the Cross.

It was daytime on February 18 when the soldiers returned with their consignment to Mucwini. This time they headed straight to the family compound, near the trading centre, hoping to quietly bury him there. They found Mama Aireni (Archbishop’s mother and family matriarch) alone at home. She firmly objected to their plan, “Long time ago, we gave Janani to God and the Church. He doesn’t belong to us anymore. He now belongs to God and His people.”

She insisted that they take the body to the churchyard by the primary school, at Wigweng, the hill beyond the little valley of Oraa-labolo. After a tense stand-off, the soldiers eventually yielded and proceeded to Wigweng, as directed by Mama Aireni. The family compound is the fifth Station of the Cross.

Trouble sinking a grave

At Wigweng, on the first day, the soldiers laboured in vain to sink a grave at three different spots in the churchyard. At night, exhausted, hungry and afraid, the soldiers abandoned the coffin inside the little church, saying they would return “after resting and eating.” In fact, they did not come back until the following morning. Their overnight absence provided a singular opportunity for a daring coterie of relatives and friends to sneak in and, using a lantern lamp, fully examine the body in the coffin. This viewing has provided us details about the desecration of the body and the gruesome wounds and torture inflicted on the Archbishop.

The Archbishop ended up spending the last night before his interment in St Paul’s ‘his church’; for this is the mabaati-roofed church that he and Mzee Ejira Kibwota (local businessman and church elder) had built at Wigweng. This, ‘his church’, became his last Station of the Cross.

On the second day, at a fourth spot identified by the locals, the soldiers finally succeeded to sink a grave. Three days after his gruesome murder and a long, concealed journey across the country, the Archbishop’s martyrdom journey came to a finality. After a simple, hurried ceremony, attended by a small gathering of relatives and family friends, the Archbishop was finally laid to rest at about 3pm on February 19, 1977. This has been his resting place ever since.

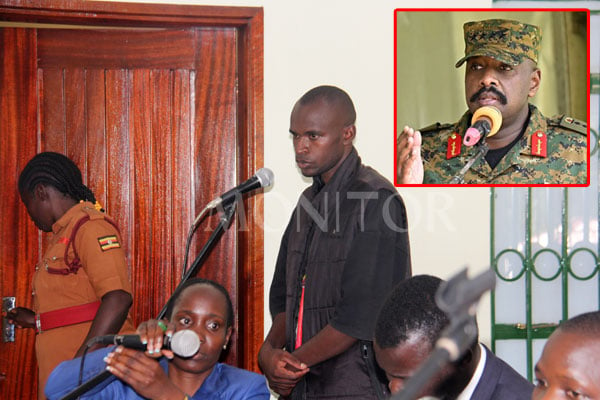

Happier times. Archbishop Janani Luwum, his wife Mary Luwum and Amin who later ordered his murder. FILE PHOTO

Since 2015, Wigweng has also been the venue for national and international commemoration of St Janani Luwum Day, marked on February 16.

Foot Pilgrimage 2020

What has been sketched above represents the exact trail and events that marked the final journey of Archbishop Janani Luwum. The idea behind planned “Foot Pilgrimage 2020” is to retrace this martyrdom journey, its itinerary and milestones; station by station, as it actually unfolded historically. It is to evoke today the spiritual and historical moments that defined this searing martyrdom.

The purpose of “Foot Pilgrmage 2020” is grateful remembrance and thanksgiving for the extraordinary life and example of Archbishop Janani, for his faith and courage, selflessness and sacrifice, humility and love. Drawing on his example and the Scriptures, the Pilgrimage will be an opportunity to renew and deepen our faith. All Christians, drawn from their various faith traditions (Anglican, Catholic, Orthodox, Pentecostal, Baptist, Born-Again, etc.) have been warmly invited to participate in this journey of faith. Led by the Church of Uganda, this Pilgrimage will be a coming together for all Christians who feel called to undertake this devotion in unity, humility and common fellowship. Most important, the Pilgrimage prompts each of us to ask of ourselves particularly: What should I learn and emulate from the extraordinary life and example of this hero of faith?

What manner of man?

What is it then about the life and witness of St. Janani that is worthy of great national and global remembrance and thanksgiving? Several things immediately jump out. His passion for proclaiming the Gospel. His deep and abiding faith. Through thick and thin, his clear, unflinching prophetic voice for human rights and social justice.

His quiet confidence and steely courage. In the face of everything; ominous threats, mortal danger, and ultimately death he never wavered. He seemed to draw from a deep inner well of confidence and tranquillity.

In life, it was very striking how Archbishop Janani exuded such natural and infectious love and joy. He always had a glowing face, with this warm, loving smile. He truly had the gift of love.

As Archbishop, he became a major uniting and healing force within a fractured Anglican Church and a country in terrible agony. As a leader, he was a great unifier and reconciler of people. He set an example of simple, uncomplicated integrity. He was oblivious to the allure of materialism. He lived a simple, unpretentious and giving life.

He was particularly devoted to young people. Even as Archbishop, with a punishing schedule, he always made time for the youth, engaging and encouraging them. He was a hunter for talent; he mentored many young people, including current Archbishop of York, Dr. John Sentamu and Archbishop- emeritus Luke Orombi.

Well ahead of his times in the Church, he began to pursue a clear vision for development, particularly for empowerment of women, poverty-reduction and rural development. One of the fruit of his development vision is Janani Luwum Church House, the edifice in downtown Kampala. He often spoke about this project; it was very dear to him.

Of physical stature, he had an imposing charismatic presence. Yet he had a natural disposition of such simplicity, humility, gentleness and warmth about him. That is why all stations of people readily felt at-home in his presence.

A turning point for Uganda

There is one aspect of the profound impact of Archbishop Janani’s martyrdom that is, sadly, not well known or appreciated in Uganda. The fact that it was the searing martyrdom of St. Janani that marked the pivotal turning point for the Amin regime and the subsequent liberation of Uganda. It united Ugandans as never before. The international community was finally and dramatically jolted from its complacency about the Amin regime. An unthinkable line had been crossed by Amin. At the international level, the impact was huge.

This became a critical game-changer. A sober realization dawned on the international community, particularly the Western world, that the Amin regime had to go. This set the stage and mood that greatly facilitated and buttressed the subsequent, and ultimately successful, Tanzania-led campaign, to remove the Amin regime.

A role model for our times

Around the world, there is great devotion to St. Janani. In many countries and churches, there is devoted celebration of his life and martyrdom. Churches, chapels and schools have been named after him all over the world.

The Church of England, in particular, has accorded the Archbishop-martyr special recognition and devotion. The Sunday after his martyrdom, a memorial service was held for him at Canterbury Cathedral. In 1978, Canterbury Cathedral dedicated a special chapel; the Chapel of Modern Martyrs prompted by the martyrdom of Archbishop Janani. In July 1998, his statue was unveiled in Westminster Abbey, in the presence of the Queen and Prince Philip. He is one of ten martyrs of the 20th century thus recognized. The other martyrs include:

Father Maximillian Kolbe (Catholic, Poland); Martin Lither King Jr. (Baptist, USA) Dietrich Bonhoeffer (Lutheran, Germany); Archbishop Oscar Romero (Catholic, El Salvador). In the Church of England calendar celebrating saints and martyrs, February 17 is celebrated as the Festival of Janani Luwum. They also have the Collect of Janani Luwum.

The values and moral bearings exemplified by St Janani are all the more compelling today because many societies worldwide are desperately searching for them. The Ugandan society, is a society in the throes of a grave moral crisis, a shauri yako culture, in which anything goes.

The life and witness of St Janani could not be more pertinent and powerful for contemporary society everywhere today than for Uganda, for Africa and for the world. He provides a radical counterpoint to what we complacently accept all around us today as the ‘new normal.’ In him, we have an authentic hero and a truly compelling role model. As a role model, his example resonates across all boundaries, both inspiring and challenging us, in equal measure. This is the meaning of St Janani’s life and witness for us today.

Olara Otunnu adapted this article from his book “Archbishop Janani Luwum: The Life and Witness of a 20th Century Martyr” (Fountain Publishers, 2015).