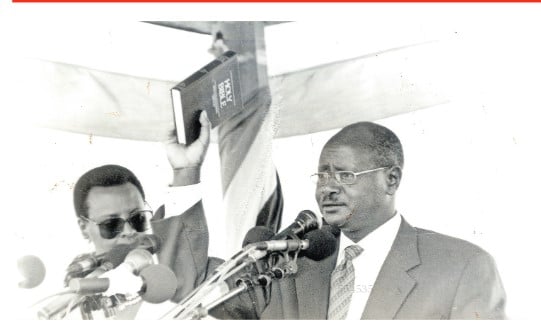

President Museveni (right), accompanied by his wife Janet, swears in for the first time as an elected president in 1996. PHOTO/ FILE

Thirty years ago, it emerged that President Museveni had agreed to open up the government’s and parastatal’s books of accounts for the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other development partners to examine in return for a reduction of Uganda’s debt.

At the time, Uganda’s debt stood at $2.6b, then equivalent of Shs2.6 trillion. Then President’s Press Secretary Hope Kivengere told The Monitor that Mr Museveni had made the offer at a dinner that was held in his honour in London, England, in June 1994.

The Monitor newspaper edition of Wednesday, September 19, 1994, quoted Ms Kivengere saying the President had told his hosts that the donors and development partners were free to inspect the government’s books of accounts since his government had nothing to hide.

Emulating Tanzania

Mr Museveni’s move followed in the footsteps of the government of Tanzania which on June 1, 1992, opened up the audit of accounts of parastatal institutions to auditors other than those from the Tanzania Audit Corporation (TAC).

Created in 1968, TAC was required to audit all parastatals and any other entities in which the government of Tanzania had a stake or as directed by the president. That meant that TAC audited the books of accounts of up to 97 percent of the parastatals in Tanzania.

That monopoly was also believed to impede the emergence of a strong private sector in the area of audits.

It was as a result of this criticism, and in line with the liberations of the economy under Structural Adjustment Programmes prescribed by the IMF, that the monopoly was brought to an end.

The passing into law of the Public Corporations Act in 1992, allowed for the directors of any parastatal in which the government owns less than 50 percent shares to appoint any qualified auditors to audit its accounts. The same law allows the minister for Finance to appoint any qualified auditors to audit the books of accounts of any parastatal in which government owns more than 51 percent shares.

Debate in House of Commons

It should, however, be noted that the matter of Uganda’s debt had already been the subject of an intense debate in the House of Commons in Britain where pleas had been made for it to be reduced or waived completely.

The House of Commons’ Hansards of March 23, 1994, reveals that the matter was first brought up by Mr Mike Watson, the representative for Glasgow Central, who argued that Uganda couldn't meet its debt obligations.

“Uganda is the fourth poorest country in the world, with a gross national product per capita of just $170 in 1991. Despite having access to every available debt relief measure already instituted by northern creditors, it still faces a foreign debt of some $2.6 billion. That debt is simply unpayable,” he submitted.

The legislator further told the House of Commons that Uganda was spending much more money on debt servicing than it was spending on the provision of social services.

“The most recently available figures show that Uganda pays about $100 million a year in debt servicing and repayments, which approximates one-third of the Ugandan government's Budget, and almost four times the amount spent on health and education combined throughout the country,” he said.

Pushing his argument further, he argued that debt servicing payments accounted for 48 percent of the value of all exports from Uganda, adding that it would have accounted for up to 83 percent if the country had met all its obligations to all its creditors.

Mr Watson said, “There is nothing more which Uganda can do itself to address its debt problem” adding that the National Resistance Movement (NRM) government should not be held solely responsible for the debts that “were lent recklessly at high interest rates to governments which squandered it”.

He called for the cancellation of Uganda’s multilateral debt with Britain and the cancellation of all debts that Uganda accumulated before the NRM shot its way into power.

Museveni differs

The Monitor, however, reported that Mr Museveni was not for wiping out Uganda’s entire debt, saying it was likely to send out wrong signals that nations can incur debts and choose not to pay back. According to the newspaper, Mr Museveni’s position was well received by the Centre for Accountability and Debt Relief based in London.

“Mr Museveni’s position offered a unique challenge to the World Bank and IMF which hold Uganda’s outstanding foreign debt, to consider suspending Uganda’s debt in recognition of the government’s commitment to keep its financial affairs fully transparent, accountable and subject to continuing audit,” the organisation noted.

Optimism

Back home, the announcement was received with lots of optimism that something was about to be done in the fight against corruption.

Whereas “elimination of corruption and misuse of power” was Number 7 on the NRM’s 10-Point Programme, the programme that had been meant to guide Uganda’s road to recovery, NRM leaders like Mr Museveni had often spoken tough and threatened drastic action, but it all turned out to be all bark, but not bite.

The Public Accounts Committee (PAC) of the National Resistance Council (NRC), the Sixth Parliament, had already stumbled upon evidence of corruption in the NRM.

In 1989, for example, Basoga Nsadhu, the member representing Busiki County in the NRC, told the House that he had discovered a major corruption scandal involving several officials in the Ministry of Defence. Nsadhu claimed that more than $100 million had been embezzled during the procurement of vehicles for the army.

Documents related to the procurement through the French Bank, BNP Paribas, through which the payments were made to the Spanish firm that supplied the vehicles, showed that the cost of purchase had been significantly inflated.

Challenged by some senior officers of the National Resistance Army (NRA), who were also historical members of the NRC, to adduce evidence, Basoga Nsadhu told the NRC that he would lay the documents before vice chairman Moses Kigongo, but just a day before he could do so, unidentified people broke into his car and made off with all documents related to the scandal. The government did not take any steps at the time to have the matter investigated.

Prof George Kanyeihamba, a former minister of Justice and Constitutional Affairs and Attorney General in the ruling NRM, who was then serving as a legal adviser to the President had a month before told attendees at a workshop sponsored by the Danish International Development Agency and the British Overseas Development Administration, where mainly senior academics from Uganda and abroad attended, that the NRM was allowing thieves to continue plundering the country’s resources as part of its strategy on enhancing national reconciliation.

“We had to reconcile the country at the expense of corruption,” Prof Kanyeihamba said during the seminar held on August 24, 1994.

Debt cancelled

It was, therefore, hoped that the thieves could now not escape the scrutiny of the donor who would demand that they be prosecuted, but that did not happen. It should be noted that the Paris Club, a group of major creditor nations that provide debtor countries with sustainable ways of tackling debt problems, announced in September 2000 that it had cancelled Uganda’s foreign debt of $145m.

The group noted that the move, part of a broader initiative backed by the IMF and the World Bank to help heavily indebted third world countries, represented its share of a programme aimed at reducing Uganda’s debt levels by $656 million. Even though the debt was cancelled, the government did not live up to its word on opening up its books of accounts to the donors.