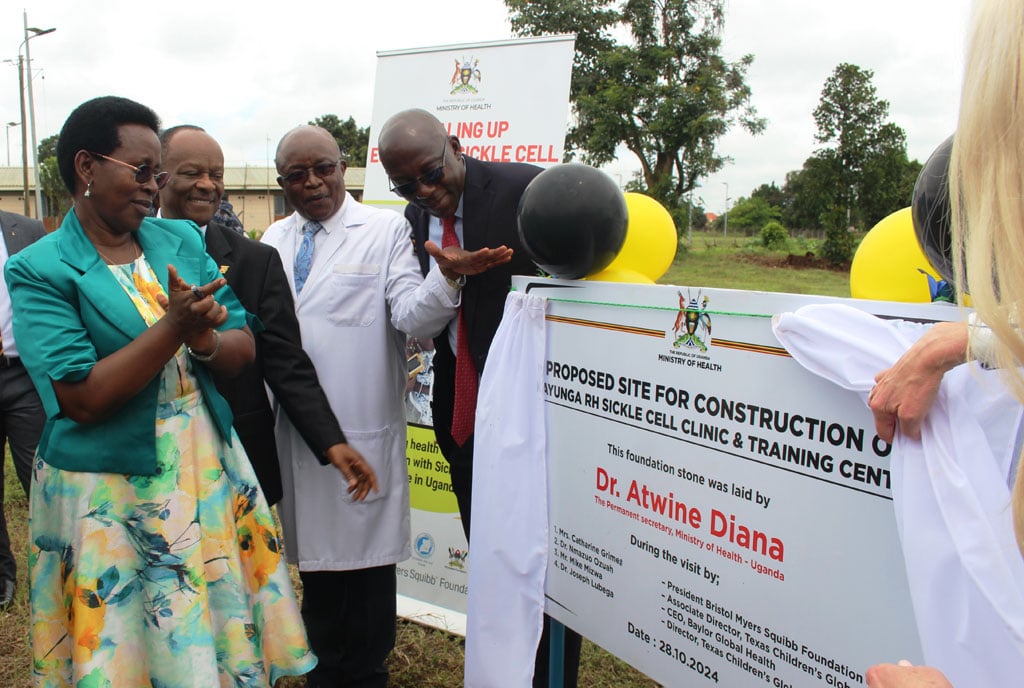

Dr Kazibwe believes that sickle cell disease is not only a genetic issue but also has cultural dimensions. PHOTO/EDGAR R BATTE

On January 1, Dr Speciosa Wandira Naigaga Kazibwe, the former Vice President of Uganda, was rushed from Iganga District in eastern Uganda to Kampala and admitted directly into the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). The previous night, she had experienced a severe headache, accompanied by vomiting and diarrhoea, leading her to contact Dr David Muwanguzi, the medical superintendent of Iganga Referral Hospital.

Her temperature at the time was a high 40 degrees Celsius, and by the next morning, it had not decreased. She was immediately transferred to Kampala, where she was diagnosed with malaria.

Dr Kazibwe remained in the ICU for four days, describing it as one of the most challenging experiences she has faced as a patient.

Why severe symptoms?

Dr Kazibwe attributes the severity of her symptoms to the fact that she carries the sickle cell trait.

“When someone without sickle cell disease is bitten by a mosquito, the parasite enters their red blood cells and is comfortably transported to the liver, where it grows, reproduces, and spreads. In someone with sickle cell disease, however, the red blood cells respond differently. When infected, these cells attempt to kill the parasite, which causes them to elongate and form a distinctive shape resembling a sickle. This elongated, sickle-like shape is what gives the disease its name; sickle cell,” Dr Kazibwe says.

She explains that abnormal cells in the body travel through the bloodstream, forming clots as they move. These clots cause significant pain for the patients.

“The clots obstruct blood flow to the bones, fingers, joints, brain, and other areas of the body. This lack of blood supply leads to a painful response in the body as it produces more new cells, which is why people with sickle cell disease often share certain physical characteristics. It is an incredibly painful disease,” she adds.

Family history

Dr Kazibwe, a surgeon with a Doctor of Science degree in Global Health and Population from Harvard's School of Public Health, currently advises the president on health and population matters. She has a personal connection to sickle cell disease, as she carries the trait and lost three younger brothers to the illness.

"Having grown up in a family impacted by sickle cell disease, I have seen the extensive social, psychological, and economic toll it takes," she shares. "Today, I see malaria imposing a similar economic burden on my country."

Reflecting on her upbringing, Dr Kazibwe reveals how sickle cell disease influenced her family’s life, particularly due to her mother's frequent hospitalisations, which ultimately led her father to take a second wife.

What is sickle cell disease?

The Mayo Clinic, a medical and research organisation, explains that sickle cell disease is a group of inherited blood disorders affecting the shape of red blood cells, the cells that transport oxygen throughout the body. Normal red blood cells are round and flexible, allowing smooth travel through blood vessels, but sickle cell disease causes them to form a rigid, crescent (or "sickle") shape. These misshapen cells can obstruct blood flow, leading to pain, organ damage, and an increased risk of infection.

"As a medical professional, I did not focus much on malaria during my training in medical school. My decision to specialise in surgery was largely influenced by my belief that many of the diseases we treat are preventable,” she explains.

“My interest in malaria developed later, influenced by my background and the connection between malaria and sickle cell disease. In regions where malaria is not common, the sickle cell trait no longer serves its historical role in providing resistance against malaria parasites in the blood. But in Uganda’s Busoga region, where malaria affects nearly 40 percent of the population, about 2.5 million people, this link is still highly relevant,” she adds.

Testing a must

Dr Kazibwe believes that sickle cell disease is not only a genetic issue but also has cultural dimensions. She explains that the disease’s prevalence is rising partly because many people are neglecting traditional practices, such as learning about a potential partner’s clan and family history before marriage.

Understanding these familial backgrounds can help people make more informed decisions about the likelihood of passing on the sickle cell trait to their children.

Dr Kazibwe recommends that couples undergo sickle cell testing before making a long-term commitment, which could reduce the risk of having children affected by the disease.

Fighting malaria

According to Uganda's Ministry of Health, around 250,000 people in the country live with sickle cell disease, including an estimated 20,000 to 25,000 babies. Dr Kazibwe, a volunteer with the Busoga Health Forum, is actively working to educate local, cultural, and educational leaders on malaria eradication strategies.

She emphasises that malaria is not only a medical issue but also a social one, with the mosquito acting as the primary vector for the disease.

She explains that mosquitoes are integral to the ecosystem; male mosquitoes feed on nectar from flowers, which provides them with the energy needed to fertilise female mosquitoes. The female mosquitoes, in turn, require protein from blood to nourish their eggs, which is why they bite humans, as well as animals such as pigs, goats, and chickens.

Dr Kazibwe also points out that the mosquitoes responsible for spreading malaria lay their eggs in clean, standing water.

This makes any stagnant water around households, such as in containers, puddles, or other open water sources, prime breeding grounds for mosquitoes, underscoring the importance of eliminating standing water to help control malaria.

DOES SICKLE CELL DISEASE PROTECT YOU FROM MALARIA?

According to healthline.com, people with sickle cell anemia (SCA), the most severe form of SCD, can often have a greater risk of death from malaria, compared with people who have SCT or no hemoglobin gene mutation. This is because malaria can trigger a sickle cell crisis. A sickle cell crisis due to malaria can result in more severe anemia, hypoxia (not enough oxygen in your body tissue), jaundice, lactic acidosis and renal failure. SCD may prevent your spleen from working as well as it should. Your spleen helps you clear infections. A dysfunctional spleen could increase your risk of a malaria infection. Results from a 2022 study in Uganda suggested that children with SCA are born with certain protections against severe malaria. But researchers also found that even low levels of infection in children with SCA could lead to severe symptoms.