Prime

When the foreign legion stays forever

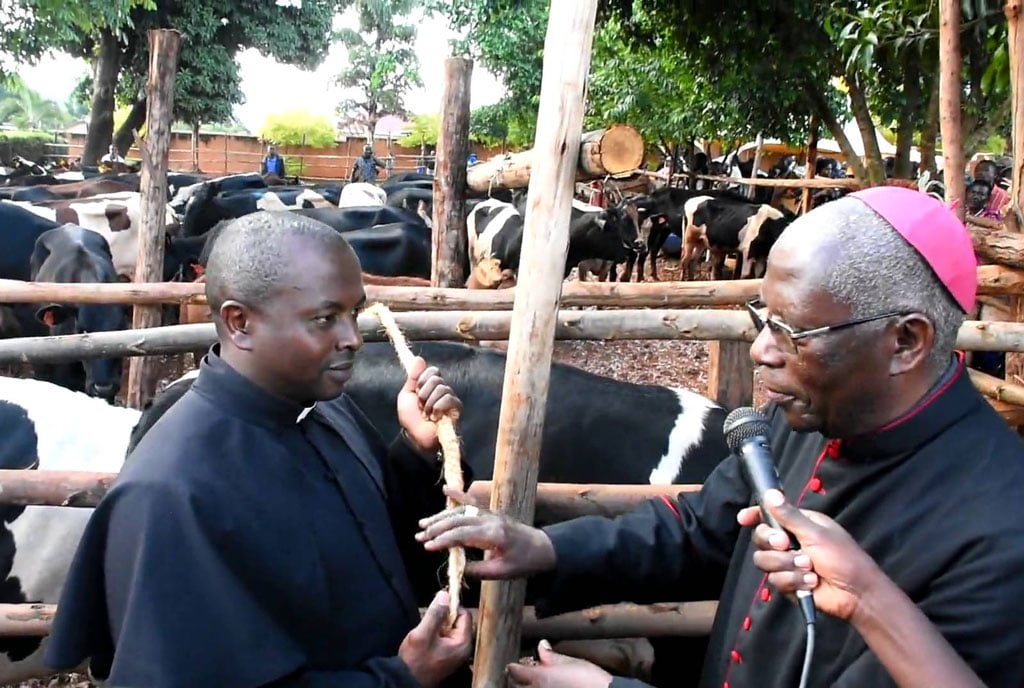

French troops carry out drills in Mali early this week. FILE PHOTO

What you need to know:

An eye for ex-colonies. A pillar of France’s foreign policy is obviously to protect its interests in former colonies with brutal efficiency and, it seems, Paris does a nice job of it in Africa

With a lengthy history of military interventions in hotspots around the globe, particularly in its former colonies and much-valued diaspora, France has in recent times resumed its reputation as the daredevil gendarme (policeman) of Africa.

“Everywhere in the world... when heritage is destroyed we will be there to battle against the groups motivated by the unfathomable stupidity which leaves all civilisations vulnerable,” the Telegraph quotes French President François Hollande, as saying of the Mali rebels last year. He was referring to the Islamists’ destruction of Mali’s ancient tombs and other cultural sites on grounds that they promoted idolatry.

And, despite recent pledges to distance itself from African politics, France is back in action in the never-ending drama of the fast-evolving continent. The motives for the move are perhaps multiple, and could include a desire to showcase the former colonial supremo’s superpower status.

Other motives could be the preservation of crucial economic interests, or the protection of endangered French nationals. Whatever the case, it is abundantly clear that the past and present occupants of the Palais de l’Élysée, the country’s seat of power, have over the years displayed a penchant for foreign military operations, some of which have ended in disaster.

Having already intervened in both Ivory Coast and Libya, the former colonial power has recently thrown in the gauntlet in Mali, albeit after suffering serious humiliation and embarrassment, following a failed mission to rescue a Frenchman held by al-Shabaab.

Unsurprising move

Past embarrassments aside, and having in the last century made forays into the most horrifying battlegrounds in the world, from Katanga in the Congo to Vietnam and Afghanistan, that the French Air Force is pounding Islamist rebels in Mali, is hardly surprising.

The bombardment took place as the rebels advanced towards the capital, Bamako, and came after France had warned that the control of northern Mali posed a security threat to Europe. As if to prepare the world for a long hot African summer, French President François Hollande declared on January 15 that French forces would remain in Mali until stability returns.

With its armed interventions having gathered pace since 1960, when most of its former colonies gained independence, France has for more than half a century arrogated itself the role of setting the direction for the political evolution of those former colonies. Not surprisingly, there have been accusations of neo-colonialism.

The claims have been particularly poignant, given that most of France’s former colonies have for years been dedicated members of La Francophonie, the global association of France’s satellites usually derisively referred to as “the Francofolly”.

That scenario has not only resulted in the protection of serving dictators, but often also in the installation of brand new ones. In return for the loyalty, and to the delight of former and current dictators and assorted crackpots riding roughshod over those former French colonies, French military intervention has over the decades also inevitably ensured that the political destinies of the former colonies were determined in faraway Paris.

But the superpower’s role has also involved the provision of military muscle in the event of external threats to its former colonies. It was thus that, in 1996, France provided badly needed military assistance to Cameroon when the country was involved in a dispute with Nigeria over the oil-rich Bakassy Peninsular.

The same happened earlier in the Comoros in 1989, when mercenaries led by the notorious Bob Denard, also French, had taken over the island’s government, at least momentarily, after president Ahmed Abdallah was assassinated by his own guard during a dramatic coup d’état. Consequently, 200 French soldiers forced the coup leader to leave the Comoros and restored order.

The same scenario was to be repeated in the country in 1995, when a new French intervention halted yet another coup, again led by the indefatigable mercenary Denard. This time round the coup was against the government of President Said Mohamed Djohar, but it was crushed by no-nonsense French forces.

As if to bolster France’s cowboy image, the list of her interventions in Africa is indeed intriguing, and goes back many decades, with the earlier ones having taken place in Gabon. It was in that country that French forces intervened in 1964 to restore a threatened president after a coup d’état that was among the African continent’s earliest ones.

France supports Bongo

Decades later, in 1990, France was again flexing its muscles in the country as its troops rallied to the support of the beleaguered regime of the late president Omar Bongo, while also evacuating foreign nationals from cities hit by rioting.

The earlier successful intervention in Gabon was to be followed a few years later by another one in Chad, where between 1968 and 1972 French troops were on the ground to put down a rebellion in the country’s northern region. The French military was back in the country from 1978 to 1980, defending the government against regrouped rebels leading a determined onslaught against it.

Despite those early French interventions, the political situation in Chad — which borders the war-torn Mali — remained chaotic from 1968 to 1972, when French troops took part in the fight against a rebellion in the Tibesti region to the north of the country.

In later years, the former colonial master’s interventions became a serial occurrence. It was thus, for instance, that the French were again back in the country in 1983 to 1984. They had meanwhile returned to Chad in 1986, carrying out further operations against the die-hard rebels.

Barely two years later, in 2008, the Gauls were again at hand with yet another intervention aimed at bolstering the tottering regime of Chadian president Idriss Deby. Mainly using their Mirage jet-fighters and Exocet missiles in the renewed intervention, the French forces were at the same time busy evacuating foreign nationals then trapped in the region following attacks by rebels operating from neighbouring Sudan.

According to reports from the era, the return to Chad by French forces was aimed at buttressing a government then under threat from rebels emboldened by support from the belligerent Col. Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya. But as things turned out, the headaches caused by the latter were to be assuaged in 2011.

That was when France took the lead in a bombing campaign against Libya. That action by the adventurous French came after the United Nations authorised action to protect civilians during a civil war. Predictably, French planes were the first to bomb Gaddafi’s forces in March, although the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato) took command of the mission on March 31, making it possible for Libyan rebels to defeat government forces and seize power.

But years before participating in the move to drive Gaddafi out of town, and even before the multiple Chadian distractions were done away with, by 1978 French and Belgian paratroopers were landing in the mineral-rich Katanga region of the former Zaire — today known as the Democratic Republic of Congo — to subdue rebels then holding European hostages as bargaining chips for political demands.

The forerunner move

That early military intervention in the Congo was to prove to be the forerunner of many more over the coming decades, which, for instance, saw French troops in 1991 deploying in Kinshasa, the then troubled capital of the former Zaire. But this time round, the French intervention was to reap notoriety, given that it followed popular riots against the regime of dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, the epitome of corruption in Africa.

Their rising unpopularity aside, French military sorties in the Congo region were to continue for years, international outcries against them notwithstanding. In 1997, for instance, as the civil war raged in the newly-named Democratic Republic of Congo, French troops were once again on the ground to evacuate endangered foreigners.

The following year the French were back in DR Congo, once again hastily evacuating foreigners from Kinshasa following the widespread unrest sparked off by the dramatic overthrow of the Mobutu regime by the late rebel-leader-turned-president, Laurent-Desiré Kabila, whose son is now the DRC leader.

But despite the ignominious fall of Mobutu, the African blue-eyed boy and an example of France’s neo-colonial forays into Africa, the fact that many French operations in Africa had left the interlopers with quite a bit of egg on their faces did not deter them from further interventions in years to come.

It was thus that, in 2003, the French were once more highly visible in DR Congo, this time providing the lion’s share of the armed forces for a United Nations joint operation to protect vulnerable civilians caught up in a raging conflict that had spread to the north-eastern Ituri region.

Much earlier, in 1997, the French had ventured into the neighbouring Congo Republic, this time having a force of some 1,200 troops. The contingent’s mandate was to rescue French and African nationals during fighting between the Congolese army and supporters of military leader Denis Sassou Nguesso.

French notoriety for bolstering unpopular regimes in Africa was to be highlighted when, in the 70s, the former colonial power gleefully participated in, and reportedly partly bankrolled, the ridiculous coronation of Jean-Bedel Bokasssa, the crazed former self-styled boss of the so-called Central African Empire.

Ironically, not much later, in 1979, French forces were deployed to depose the former avowed buddy of the French, whose shameless adoration of the former colonial masters provoked many guffaws around the world.

Not done with the Central African Republic, the French were back there in 1996-7, launching two bids aimed at restoring law and order following military mutinies in the still unstable country. The intervention was also aimed at protecting the regime of President Ange-Felix Patasse, then a valued ally.

Similar interventions are on record as having occurred in other former French colonies like Gabon, Togo, the Comoros Islands and Côte d’Ivoire, also known as the Ivory Coast. In the latter country, in 2002 French forces mounted “Operation Licorne” to help Westerners trapped by a military uprising that had effectively divided the country into two.

Rambo-style, the French were, in 2004, deployed to destroy the country’s tiny air force after government forces bombed a French base. Ironically, earlier in 2011, French forces inside the country had tipped the balance in the then raging civil war that had erupted after the refusal of disgraced former president Laurent Gbagbo to step down and accept the election victory of Alassane Ouattara as president.

Gbagbo was consequently ousted and Ouattara installed. Other French adventures in Africa were more low-key, as was the case in Togo in 1986, when French reinforcements were sent in after a coup attempt that eventually failed. Once again, France had successfully propped up the regime of yet another notorious African dictator, this time in the person of Gnassigbé Eyadema, who had proved to be an avid coup-maker in his own right.

Even before the advent of decolonisation, France — unwilling to let go — had indeed taken up arms in a determined bid to hold onto some of its most valued colonies.