Prime

Court upholds Uwera sentence

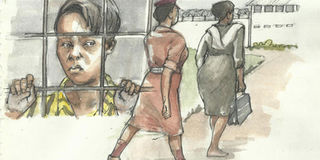

Uwera kept apologising to her husband. She was in constant grief and worry. PHOTO/ILLUSTRATION

What you need to know:

- In truth were these relatives capable of pushing for murder charges? Did these facts not affect the credibility of the witnesses and the entire case?

The death of Juvenal Nsenga and the subsequent trial and conviction of his wife Jackline Uwera Nsenga for murder will probably keep reverberating in legal echelons in the region. It is a case in which the application of legal principles will forever be questioned.

Background

The unfortunate series of events occurred on January 10, 2013 at Bugoolobi, Nakawa Division in Kampala, where the couple lived.

Uwera drove a car that rammed in the gate and then hit her husband who had come to open the gate for her. Nsenga died of his injuries a few hours later.

Uwera did not know who had come to open the gate for her that night and prosecution did not prove this fact beyond reasonable doubt or at all yet court then relied on the relationship between Uwera and her husband to convict her of murder.

Forensic evidence

The forensic evidence clearly proved that the incidence that led to Nsenga’s death was an accident but court, using circumstantial evidence, argued that it was a deliberate act.

There was an obvious alternative explanation of how Uwera rammed the car into the gate but court compared her actions to those of the terrorists that flew the hijacked planes into the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001 in New York, USA, notwithstanding the subsequent evidence found against the terrorists.

The defense team, though, did not offer a credible alternative explanation to what could have happened but the law is clear that the burden of proof lies with the prosecution throughout the trial.

Uwera’s conduct

One of grounds that court purportedly relied on to convicted Uwera Nsenga of the murder of her husband was her conduct before, during and after the commission of the crime. She was clearly distressed in the immediate aftermath of the incident.

A brother of the deceased testified that Uwera was hysterical when she called him and informed him about the accident. She also laboured to seek help and rushed her husband to the nearest hospital.

And further, while on their way to the hospital, Uwera kept apologising to her husband. She was in constant grief and worry that her marital woes would be put in question to infer that she intended to kill her husband.

The Directorate of Public Prosecutions (DPP), however, submitted that given the circumstances of the case, the behaviour of Uwera should not be misinterpreted as distress arising out of the incident but rather distress arising out of what the world would think of her actions.

Testimony

Relatives of the deceased testified in court that Uwera was asked by her husband to leave the room he was admitted in. Uwera’s demeanour was described as calm in the hospital even when her husband’s condition was critical. To the prosecution this was not the conduct and condition of a distressed wife whose husband was fighting for his life. Was not, and is not, in truth, Uwera, a calm and non-violent lady by nature? Evidence on court record was that Uwera and her husband were not known to have engaged in physical fights.

The court of Appeal noted that Uwera drove her husband to hospital after the accident. However prior to that she had called her husband’s brother and told him that because of the marital misunderstanding between her and her husband, people would think that she had tried to kill her husband. The Court of Appeal ruled that Uwera made this call to cover her trucks. Court did not, however, elaborate on how it arrived at this ruling.

The Police had written to the office of the DPP with advice that Uwera be charged with the offence of causing death by a rash and negligent act since there was insufficient evidence on record to prove malice aforethought so as to justify charging her of murder.

Court of appeal

To the police the death of Nsenga was the result of an accident. The Court of Appeal was not persuaded by these submissions; to the court, it is not the place of the police to tell the DPP how to do his job. The Constitution stipulates that no one can direct the DPP on how to do his job.

The trial court considered the marital acrimony between Uwera and her husband as one of the pieces of circumstantial evidence offering corroboration of malice aforethought. The trial court held that relatives of the deceased had given credible evidence that the couple lived an estranged life, slept in separate bedrooms; neither greeted each other as husband and wife although the deceased continued to provide for the family. To the trial court Uwera down-played the seriousness of the situation by referring to these problems as mere challenges.

To court this could not be a manifestation of the ordinary wear and tear typical in marriages but a marriage characterized by mistrust, hatred, manifestation and threats.

The accumulation of these elements over a long period of 10 years resulted in the formation of a tinderbox, which constituted the bedrock of Uwera’s intention or malice aforethought to kill her husband.

However, no evidence was led to show unique marital woes to corroborate and or prove malice aforethought and there was no evidence on record to suggest that there was a clear escalation of unique marital challenges about the time of the accident.

The trial court apparently ignored the prevalent family strive between Uwera and the relatives of her husband and the imminent fight for Nsenga’s estate worth Shs50b.

When Uwera lodged a caveat on the application for the grant of the letters of administration of the estate, her in-laws approached her lawyer with an offer that if she removed that caveat, then they would stop pushing for the murder charges.

In truth were these relatives capable of pushing for murder charges? Did these facts not affect the credibility of the witnesses and the entire case? Only time will tell but invariably, irreparable damage has already been occasioned.

To be continued...