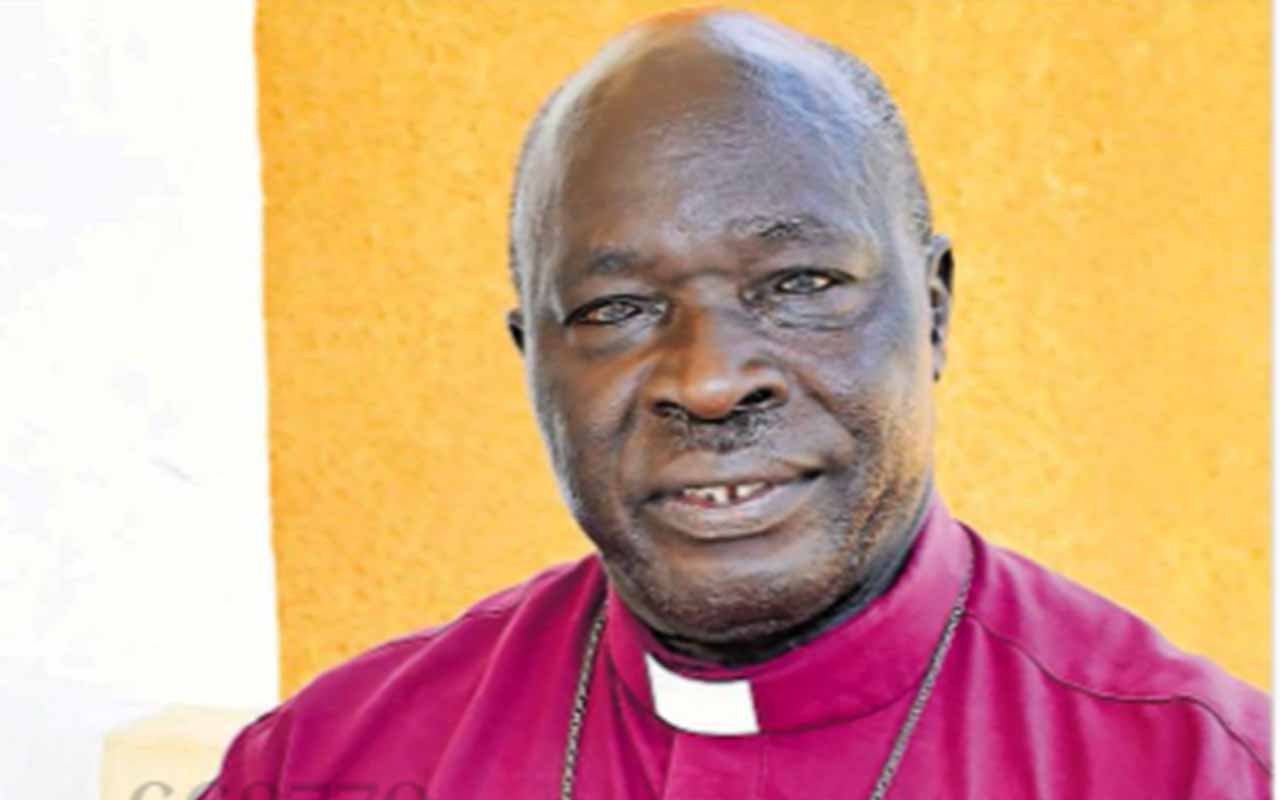

Retired Bishop Odurkami. Photo/Tobbias Owiny

Retired Bishop Odurkami played a key role in resolving wrangles over who should be bishop in the Church of Uganda dioceses of Kitgum, Busoga and Kumi.

Upon riding his bicycle for 42kms from Aduku Town Council to Lira Central Police Station in early 1993, John Charles Odurkami could not pass the physical interview to be recruited into the Force because of his height.

After Idi Amin came to power in a coup detat in 1971, the resulting insecurity led to poor Uganda Certificate of Education exam results, which prompted his decision to join the police.

From his residence at Boke village, Boroboro, in Lira City, the former bishop of Lango Diocese explained during an interview that he could not be recruited because his height was below the required one.

The former bishop said by then only tall men and women were recruited to the police and army.

“I went to join the police force; I travelled from Aduku to Lira CPS, and the OC asked me to move to the right and backwards. I did not know he was positioning me on a scale tagged on the wall. I heard him say I was very short to be recruited, and when I looked back, there was a calibration on the wall,” he said.

He said his dreams of being a pilot were shattered because of his bad performance in the exams.

However, lady luck smiled upon him at a June 1973 Scripture Union function at Aduku Archdeaconry when he was nominated to be trained as a church cadre due to his dedication to the Church.

The training would later shape him for recruitment into a Church army captain.

Of the 45 who attended the Kampala training, only two were nominated for the one-year church army course in Nairobi, Kenya. While 45 candidates from Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Zaire, and Rwanda turned up for the training, only 15 candidates were needed. They were subjected to a rigorous one-week interview process.

The Church Army Captains is a branch of the Anglican Church where young Christians are recruited and trained on leadership and conflict management, and they are deployed in areas such as those experiencing insurgencies, in police and army barracks, among others.

Upon his graduation and commissioning from Nairobi in November 1975 as a Church Army officer, he was appointed the warden of St Augustine Community Centre in Lira Town.

“Bishop Benoni Ogwang appointed me with the instruction that he was deploying me there to restore sanity and make the centre a true Christian centre. There were a lot of immoralities happening there. Christians had bad conduct,” he said.

Bishop Odurkami, the first captain from northern Uganda, at the same time, assisted the parish priest/vicar of St Augustine, a role he performed until 1977 when Janani Luwum was killed and Bishop Melchizedek Otim, his superior, fled to exile.

“As a captain, I was tasked to ensure that the Church’s principles and standards remained consolidated. At the peak of the insecurity, the church suffered at the hands of former President Idi Amin,” he said.

In 1979, the late Bishop William Okodi, who was appointed assistant bishop in the absence of exiled Bishop Otim, ordained Odurkami a deacon and deployed him to the newly-established Anai Parish.

However, Odurkami’s duties were disrupted by the 1979 liberation war that ousted Idi Amin from power.

When Bishop Otim returned a year later in 1980, he ordained Odurkami as a full priest.

He was then sent to Tanzania for training.

“We were sent to Tanzania, but because Okodi and Otim had their conflicts, his office (assistant bishop), which was to sign our accreditation for residency in Tanzania, frustrated us by declining to do so once Otim went to India for a sabbatical, and we protested and returned to Uganda,” he says.

He adds: “When the bishop (Otim) went to India for a sabbatical, the assistant created all reasons to frustrate us as revenge on his boss. In Tanzania we were denied residential permits to get accommodation, feeding and access to the training facilities because he did not sign.”

Once they returned to Uganda, he said the bishop insisted that either they go back or pack their belonging and leave the Church even when they explained to him the situation they went through.

“We opted not to go back to Tanzania and expelled ourselves. But a year later, when Rev Yokoyadi Opollo Apelo then the vicar of St Augustine, was appointed the diocesan planning and development officer, the bishop was forced to reabsorb me back into service,” he said.

Rev Opollo had become overwhelmed with the two roles, forcing him to resign from the vicar role. This created a vacuum of leadership. Odurkami was appointed the new vicar of St Augustine and he served from between 1980 and 1983.

On a mission

During his tour of the diocese, the newly-appointed Archbishop, Dr Yona Okoth, appreciated the work ethics Odurkami, who acted as an interpreter for him.

Archbishop Okoth requested the bishop to transfer Odurkami to Kampala as the archbishop’s chaplain.

“I did not want to stay in Kampala and I declined because I did not like their policies and generally I feared Kampala, from stories I heard,” he said.

Serving as the diocesan mission coordinator, in 1989, Odurkami secured sponsorship for a degree study programme at Makerere which lasted until 1991.

Archbishop Okoth had not yet given up on him and now did not want further excuses for declining to work at his office.

At the position, Odurkami served alternately as the provincial mission coordinator and occasionally served as the provincial secretary once the incumbent officer was on leave, until 1994.

When Dr Okoth retired and Livingstone Mpalanyi Nkoyoyo was elected archbishop, he made Odurkami his chaplain.

Odurkami served under Archbishop Nkoyoyo for five years until 1999, during which the Busoga Crisis (of Bugembe) erupted.

“They were angry Christians, others did not want Bishop [Cyprian] Bamwose, so that crisis was a terrible one, they stoned his car and smashed its windscreen, and so he retired leaving Busoga in that state of confusion and when Nkoyoyo came, he thought he would manage it,” Odurkami said.

He said Archbishop Nkoyoyo was also unable to resolve the crisis, just like his predecessor, Dr Okoth.

“They also stoned him and his car and so he decided to abandon the whole thing, but then kept delegating me. I would, every Sunday go, and meet the leaders, pray with them but tell them the truth to their face. When I talked, they would shout at me and I would also shout back at them,” he said.

He added: “So we struggled with them for quite some time but when one day I delegated Can Jackson Turyagenda to go there and he was nearly lynched, I changed the approach, I used security,” he added.

“The following Sunday, I went to Jinja CPS and told the police about the hooliganism and asked for personnel. I mobilised 10 armed police officers ahead of me and they deployed before I arrived, and that was the day when we eventually captured Bugembe, with some plain-clothed policemen also deployed inside the church to quell any confusion that may erupt,” Odurkami said.

He added: “That day they came to their senses, after church service, they went and bought padlocks, changed and kicked Lubogo out of the church and that was when the archbishop started coming back to serve there, he added.

Consecration

In early 2000, Bishop Otim wrote a letter to Archbishop Nkoyoyo requesting to be allowed to return to Lango Diocese were he had been identified as a potential candidate to replace Otim, who was retiring soon.

He said: “I came back amidst a lot of confusion in the diocese where I was to serve as the diocesan dean of All Saints Cathedral, Boroboro. However, in August Bishop Otim was retiring and nominations were done and our names were sent to the House of Bishops where I was elected.”

At the time of helping to carve West Lango Diocese in 2014 to lessen his roles at Lango Diocese, a serious crisis had erupted in Kitgum Diocese which required his involvement to resolve.

In 2015, the archbishop asked him to go and care of the Kitgum Diocese while also the Bishop of the Lango Diocese until 2018.

He spent much of his time in Kitgum trying to sort out the problems in Kitgum Diocese.

The wrangle pitted supporters of the late Bishop Benjamin Ojwang against those who did not want him at the helm.

Odurkami said he endeavoured to reconcile the warring parties and promote unity among the faithful.

“Eventually we withdrew and pulled out the case from court, united the two parties and when we started talking about the election of the new bishop in Kitgum, they wanted me to remain their bishop and that they did not want a Kitgum or Pader native to be the next bishop,” he said.

After resolving the Kitgum Diocese impasse, Odurkami oversaw the election and installation of the new bishop, Wilson Kitara, in November 2018.

He was later handed the next assignment to go and do the same in Teso sub-region at Kumi Diocese.

I did not want to go to Kumi because I was retired and tired, language was also a barrage, and at one point I asked the archbishop to assign the task to someone else but he objected.

Odurkami said when he went to Kumi in early 2019, he faced an environment full of rebellion and rejection.

In Kumi Diocese, Odurkami said his office was locked thrice and he faced threats against his life.

“In February 2020, from nowhere we saw a group with placards storming the place and chasing us away and I would work from under a tree while police insisted on escorting me although my major message to them at physical meetings, funerals, radio talk shows, etc. was to cease fire and reconcile,” he said.

“God gives me the courage not to fear because when he calls I know he will protect me. In Bukedea, at one moment, they pulled away chairs from us at a meeting, confiscated our Bibles, and also vandalised our car while threatening to slaughter or shoot us dead if we dared to return there,” he narrated.

Amidst all the difficulties he faced in such missions, Odurkami said he was motivated by the positive results of his works and the fact that God always protected him.