Exports. Coffee is Uganda’s second leading export after gold since the Financial Year 2021/22. PHOTO / FILE

Back in the 1990s, Uganda adopted several reforms. One of them was creation of semi-autonomous agencies. The architects of these (largely donor-driven) reforms promised enhanced efficiency and State capacity to deliver services by sidestepping bureaucracy in the mainstream ministries.

Three decades later, evidence showed that instead, the reforms had fragmented government, increased the cost of running it, caused overlaps and duplications, and in some instances eroded accountability, especially to the citizens.

‘Agencification’ also led to policy incoherence, since it shielded implementers from the direct scrutiny by policy makers. In the end, Ugandans have continuously expressed frustration due to poor service delivery.

Some even think that the government does not care about what is taking place. The popular view among Ugandans is that government is good at making policies and plans but poor at implementing them.

Our 2019 research on Uganda’s implementation record found that implementation can be successful only when “street-level bureaucrats” (the people closer to the real problems) are offered key roles in solving the problems. Also, when there is effective command and control over all the actors.

Earlier, in 2008, the government hired the Oxford Policy Management Limited — a UK based firm — to conduct an independent evaluation of the PEAP to draw lessons for the development of the processes for the NDP that was being formulated then. They stated that “the effectiveness of the PEAP was impeded by poor implementation.” They attributed the poor implementation in Uganda primarily to what they called “Weak collective decision-making and oversight”.

Ramathan Ggoobi says the 2025/26 resource envelope is projected to amount to Shs57.4 trillion. Photo / File

To be honest, agencification is not a Ugandan problem. Many countries around the world that implemented similar reforms have experienced similar problems. The difference is that on realisation, many other countries rationalised their governments to restore coordination between policy and implementation. Some of these include Australia, New Zealand, USA, the United Kingdom, Jamaica, and Ethiopia, among others.

Uganda is just joining them. The President, while meeting MPs in September this year, asked an important question; “Now that agencies have become duplicative, expensive, and largely unaccountable, and some of you are saying ministries are bureaucratic, slow and lack some critical human resources, what is the best way forward? Should we close ministries and retain agencies?” This was a critical question, and it made the MPs realise it is not wise to keep both for reasons already mentioned.

However, they raised a concern that since some of the ministries were not well prepared to immediately absorb the roles currently implemented by the agencies, a transition period of three years should be allowed to build the capability of those weak ministries.

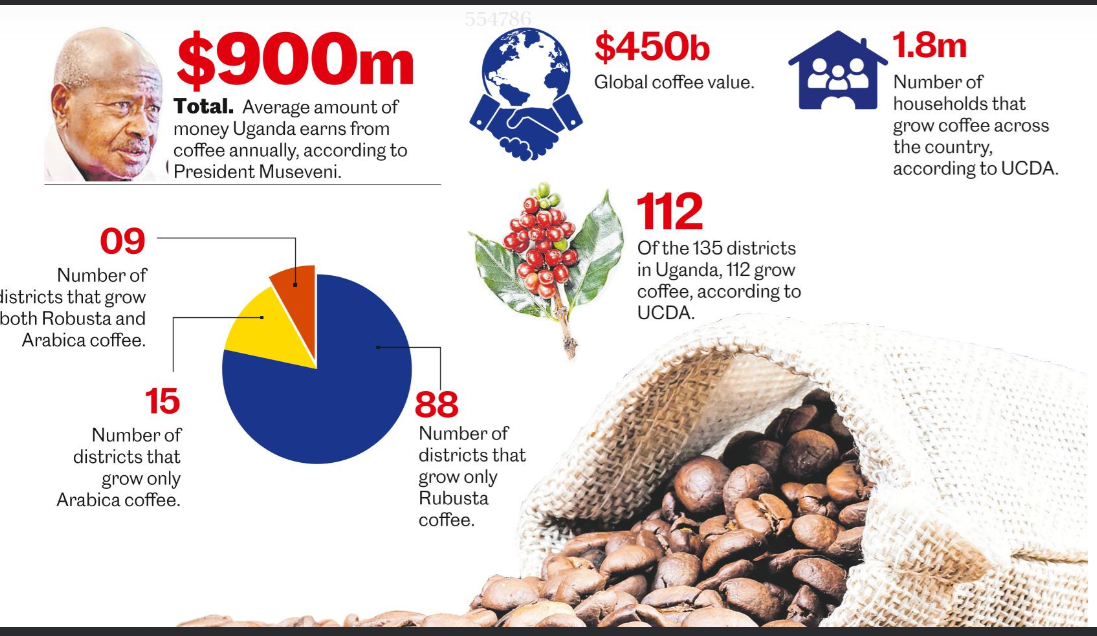

The President agreed. But then, some of the MPs have since changed their mind and insisted that some agencies be exempt altogether from the rationalisation. Their argument is that these agencies, such as Uganda Coffee Development Authority, are so critical that their rationalisation could cause disruptions in the sectors they regulate or implement. I also read in mainstream and social media statements attributed to key opinion leaders raising similar fears. It is understandable since some of them were part of architects of the reforms that ushered in agencification.

Well, seven years ago, the President, in his July 17, 2017 letter asked similar questions:

(i) Why have agencies where there are departments of government dealing in the same area of responsibility? (ii) How much is being spent on sustaining agencies?

(iii) Why separate the policy role from regulatory role for non-commercial bureaucratic portions of government?

(iv) Why have boards for money consuming agencies other than money generating agencies?

(v) Is it a fair and efficient decision to consolidate, downsize and rationalise and pay well the non-commercial portions of state employees?

(vi) Is it better to consolidate the public service employees into two categories: policy, regulators and implementers; and money makers running a few parastatals.

To answer the President, a study group comprising different professionals including economists, statisticians, lawyers, public administration experts, legislators, military professionals, and a strategist, spent half a year analysing tonnes of data to provide a scientific solution. The team reviewed 22 ministries, and 146 agencies, authorities, boards, bureaus, and commissions.

The team carried out a “functional analysis” of these entities which unearthed overlaps, duplications and in some cases outright irrelevance of some of the agencies in the delivery of Uganda’s development aspirations.

In addition, the team conducted a “financial analysis” that dug out the cost implications of the duplication and overlaps in government. It was established that whereas agencies employed fewer workers than the mainstream public service, they spent more money on salaries and operations than the line ministries.

On average the salary paid to a “median officer” (one representing majority of others) with a master’s degree working in an agency was paid 10.4 times higher than an officer with similar qualifications and responsibilities in the mainstream public service.

As a result, agencies spent about 30 percent more on salaries than what the ministries spent. Indeed, in FY2017/18, the wage bill for agencies (Shs1.3 trillion) almost doubled that of ministries (Shs693 billion) although the agencies employed fewer workers (3,905) than ministries then (18,532).

In addition, agencies were found to be big spenders on allowances (Shs362 billion), gratuity and NSSF (Shs211 billion), travel (Shs180 billion), fuel (Shs59 billion), workshops (Shs47 billion), consultancy services (Shs75 billion) etc. On most of these items, agencies outspent ministries, yet the latter employed more people.

The argument has always been that agencies deserved the higher wages and operational funds since they were comparatively better performers at service delivery. However, Ugandans and research have often cited implementation failure as one of Uganda’s main challenges.

The reasons for this are embedded in the institutional framework. The architects of reforms promised that when delivery of public service is shifted to semi-autonomous agencies Ugandans will get better results since government bureaucracy would be evaded. What have been the results?

Did agencies excel at service delivery? Haven’t we heard people saying that instead it seems the reforms simply “agencified” and liberalised corruption and abuse of public resources? It’s upon this functional and financial analyses that recommendations were made to rationalise government and adopt a whole-of-government approach to service delivery and wealth creation.

Therefore, this article intends to shed some more light on the overall objective of rationalisation. I hope some people who were reducing the entire exercise to money, and those politicising it will get a few facts.

Politics should be about defining priorities. What is our priority as a country? We keep decrying poor implementation and we do not want to face the trade-offs required to deal with the problem! What I want to emphasis here is that restoring government command and control structure to ensure effective implementation of government work, to deliver services to Ugandans, is the main objective of rationalisation.

Government had become overly fragmented and the cost of running it skyrocketed due to overlaps and duplications.

It is hoped that with rationalisation— which soon should extend to the ministries themselves, local governments, as well as other arms of the state—government will deliver services in a more effective yet efficient way, facilitate wealth creation, and ensure accountability with results to the citizens.

The writer is an economist and the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Finance, and Secretary to Treasury