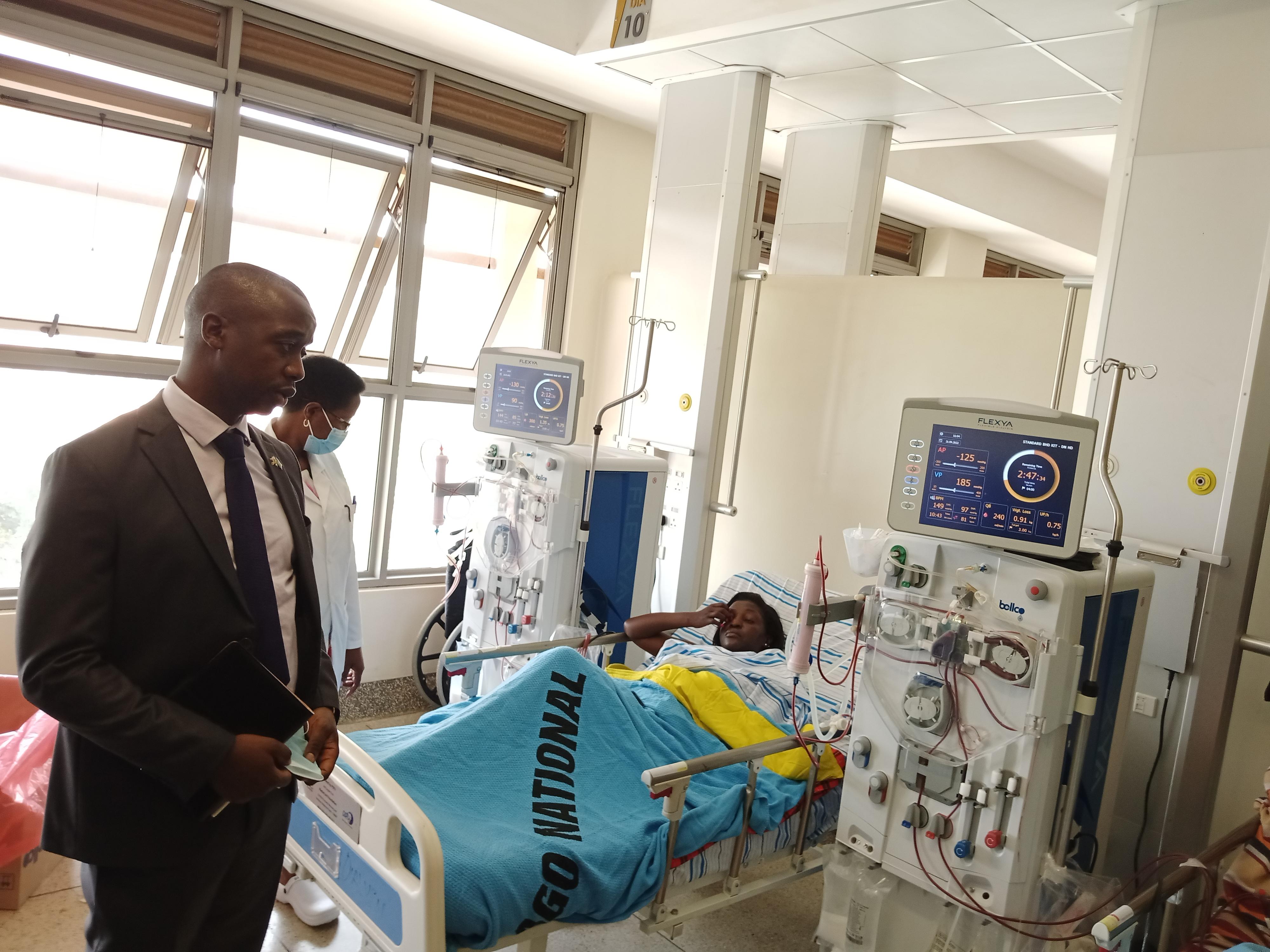

Doctors attend to a patient at Mulago National Referral Hospital in 2023. The cost of a kidney transplant at Mulago is estimated at around Shs55 million. PHOTO/FILE.

Irene Nerima, 30, is one of the patients with end-stage kidney disease at Mulago, the country’s largest hospital. Ms Nerima’s home in Kisaasi, a city suburb, is only a few kilometres away so she is able to shuffle between her home and the hospital where a dialysis machine does what her kidneys are unable to do anymore: remove waste from the blood.

When Ms Nerima heard last December that Ugandan surgeons had successfully conducted the country’s first kidney transplant at Mulago, she was filled with hope. A donated kidney could save her life and also save her from the expensive dialysis. That hope broke through dawn like sunrise then turned into scorching frustration. Now, as it descends over the horizon, it has degenerated into desperation.

“I can’t keep waiting because a time will reach when I will even fail to get money for dialysis and the more the toxins will build in the body,” a distraught Ms Nerima said, waiting for her turn at the hospital.

“I am to go to India for the transplant. I come for dialysis once a week because I don’t have money to come two times [as her doctors recommended]. I need Shs250,000 every day I come for dialysis. We have managed to raise Shs50 million for the transplant in India. We need Shs100 million,” she added.

Mulago bills

The cost of a kidney transplant at Mulago is estimated at around Shs55 million. With the money she has managed to raise, Ms Nerima could have the surgery done if she found a donor with a match. She hopes that she can raise the Shs100 million in time.

Others need time and money. Jane Achola’s husband, Gideon Omony, is a teacher at Aloi Fatima Senior Secondary School and a veteran radio presenter in Lira. He is also seriously unwell.

“He was diagnosed with chronic kidney disease in February when he was admitted to Lira Regional Referral Hospital and the doctors recommended a kidney transplant,” Ms Achola told this newspaper. “We shall be going to India and we need Shs120 million. He goes for dialysis twice a week and each session costs Shs80,000.

“There is also an injection to boost his blood level; we buy each vial at Shs70,000. He is fairly stable but weak. He can’t walk for long and he can’t do his job of teaching. We have managed to raise Shs62 million and we still need more.”

The successful transplant of a kidney last December followed years of preparation, including training Ugandan doctors abroad. The expected follow-on surgeries have, however, not happened after the surgeries were suspended in March by Health Minister Jane Ruth Aceng.

Dr Aceng said all organ transplant surgeries were halted to allow for the establishment of a Human Organ Transplant Council which is supposed to regulate them. The minister told Members of Parliament on March 27 that her ministry would spend Shs3.6 billion on training and benchmarking from other nations and another Shs1.4 billion on the activities of the Council.

“We have halted all transplant activities because we need a Council in place. Yesterday, as you [MPs] were touring the surgical exhibition, you saw the ready facilities. They can’t operate unless we have a Council, and the Council has to be trained because it is virgin land in Uganda,” Dr Aceng said.

The Uganda Human Organ Donation and Transplant Act, 2023, which President Museveni signed into law in March 2023, provides for 15 functions of the Council. These include regulating, organising, and supervising the national organ, tissue, and cell donation and transplant; regulating designated transplant centres and approved banks; enforcing standards; regulating the allocation of organs; and, overseeing the national waiting list.

Seven months later, the Council is yet to be set up.

Budget loopholes

Dr Charles Ayume, the outgoing chairperson of the Parliamentary Health Committee, who was been at the forefront of developing the Act and pushing for the transplants, said the Shs5 billion budget which they had endorsed for the establishment of the Council was not prioritised.

“No money was allocated for organ transplant,” he said. “It was an unfunded priority.”

In April, as the budgeting exercise was nearing completion, surgeons urged the government to ensure that money was provided for the establishment of the Council. In response, the Permanent Secretary of the Health Ministry, Dr Diana Atwine, gave assurances that although no money had been earmarked for the body, resources would be found to ensure that it started its work.

“Parliament members are part of us, they argue, ask for money but in the end when the final decision is made, they will tell you this is the money you have, so sort yourself within the budget,” she said. “In this case, we will have to suppress some activities deliberately, and we find money to operationalise the council so that these people [doctors] are motivated to continue working.

“Because they [doctors] have already demonstrated that they are able, they have built the skills, have the will, all they need is just us to facilitate them – put the right equipment, staff. But how do you do this without resources,” she added.

Pain all around

Shortages of equipment and medical supplies in public hospitals have over the years been covered up by private medical establishments. Anticipating demand for organ transplants, these privately-owned facilities have invested in the skills and equipment needed.

Dr Michael Okello, a liver transplant surgeon at Lubaga Hospital, said their facility is ready to start doing transplants – but the absence of a regulatory body in the form of the council has affected both public and private hospitals.

“Most of us that the President sent in 2017 to India for training were in high-volume transplant centres. When we came back, there was no law but now that we have the law, we don’t have the transplant council,” Dr Okello said.

He added: “What [the president of the association of surgeons, Dr Frank Asiimwe] went through to have that [first] transplant done people don’t know. He had to run around, get approval – right now you can only get the approval from the minister [of health who is also responsible for appointing the transplant council]. But for sustainability and continuity, we ask the ministry of health to at least have the transplant council appointed so that other members can come on board.

“Rubaga [Hospital] invested over one billion shillings to establish a state-of-the-art hospital based on our knowledge and guidance from what we saw in India. But to our dismay, our theatre is redundant waiting for the transplant council to be appointed.”

Burden of disease

According to information from the division of non-communicable diseases control at the Ministry of Health, Uganda is registering increases in kidney, liver and heart disease and other conditions that may require organ transplants.

A 2022 report by Dr Robert Kalyesubula and other colleagues at Makerere University Medical School estimated the prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the community at two to seven percent. It was estimated at 15 percent among people living with HIV or hypertension.

“Kidney disease in Uganda is increasing and is among the top 10 causes of death, with a case fatality rate of 21 percent among patients admitted with chronic kidney disease (51 percent with end stage kidney disease),” the study noted.

Mulago and Kiruddu hospitals provide the most dialysis sessions with roughly 2,600 per month, in addition to sessions at regional public referral and private hospitals, according to information from the doctors handling kidney patients.

Dr Kalyesubula, who presides over the Uganda Kidney Foundation, said the major drivers of kidney disease are non-communicable diseases like “diabetes, hypertension, chronic use of drugs such as anti-retroviral therapy, infections, and then sometimes cancers’’.

He said: ‘‘Prevention relies on taking a personal interest. One, looking at our lifestyles, we should be able to do exercise. We should watch what we eat, particularly we need to eat a healthy diet which is full of vegetables.’’

He advised against adding raw salt to food and excessive consumption of alcohol. Dr Kalye subula also recommended regular kidney checks.

“Just take, say, a urine test or a blood test and you know what your kidneys status is. If you have any of the above chronic diseases, ask your doctor,” he said. “Avoid smoking, taking a lot of alcohol, also fried foods. These are key drivers of kidney disease. We should also make sure we take enough water, eat enough fruit and exercise regularly.”