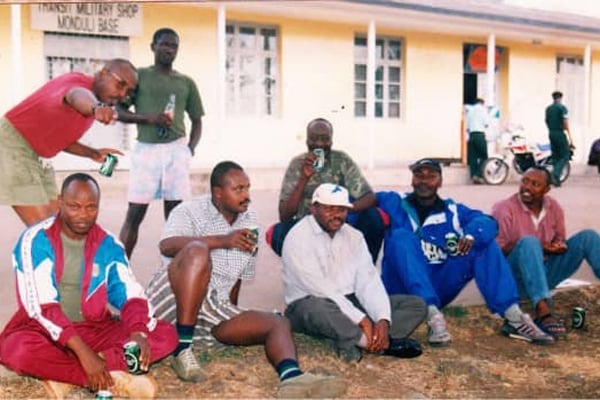

Col Ndahura Atwooki Birakurataki (left, seated) with colleagues during a course in Monduli in Tanzania in 1998. PHOTO | COURTESY OF ANDREW BAGALA

After toppling the Tito Okello government, Col Ndahura Atwooki, then a sergeant, found himself swapping his military fatigues for a suit. This was mainly because assignments from his supervisors then, including Dr Kizza Besigye, a minister at the time, and Amanya Mushega, the then chief political commissar, saw Col Ndahura live out of a suitcase. But it didn’t take long for him to slip back into his military fatigues.

“My commanders sent me to northern Uganda in the 27th Battalion for commissar tasks and later to the 59th Battalion. A year later, rebel leader Alice Lakwena became a thorn in the country’s flesh,” Col Ndahura says.

Lakwena’s rebel group was based in the northern and eastern regions. It comprised experienced fighters from the previous armies and it was well equipped. Col Ndahura says Lakwena was “a very fierce fighter.” It didn’t help matters that the morale of soldiers in the Ugandan army “was very low, forcing some to carry out an unsupervised retreat.” So, Col Ndahura further reveals, “the leadership thought it wise to establish political commissars at the front to improve the morale of the soldiers.”

In 1987, Lakwena successfully captured Corner Kilak, a few miles from Karuma Bridge in northern Uganda, following an offensive. The reason the Ugandan army was on the back foot was quite apparent.

“As a political commissar, I was sent to the front to prevent soldiers from fleeing and also give them morale,” Col Ndahura recalls, adding: “When I talked to the commanders and their men on ground, I found out that there was a real shortage of manpower. You would find a company commander who is supposed to have 150 soldiers with only 25.”

There were also a lot of ghost soldiers and leadership challenges. The commanders couldn’t report the ghosts since they would be exposed as being corrupt. Lower commanders too didn’t report the shortage of manpower for fear of reprimand.

Farsighted

President Museveni was bothered by Lakwena controlling Corner Kilak, so he deployed Maj Gen Fred Rwigema (RIP) as the overall commander to carry out a counterattack. Maj Gen Rwigema was so eager to implement his commander’s directives and he was about to go on the offensive.

“I advised him that we can’t carry out a counteroffensive. I said to him, ‘Afande, we have no troops.’ The situation was so bad that section commanders were in reality platoon commanders yet we were facing a very superior force,” Col Ndahura says.

Being thin on ground meant if the counterattack failed, they had no option but to beat a hasty retreat. This would mean, adds Col Ndahura, Lakwena’s force pursuing them when they were in a weak position. Col Ndahura was convinced any misstep would change the course of the war since NRA didn’t have enough forces at the rear, between Karuma Bridge and Wakiso District either. If a failure happened, Lakwena was to advance to the capital city.

Maj Gen Rwigema agreed and duly halted the counteroffensive. As they pondered what to do next, they got intelligence that Lakwena was also planning another offensive.

“We looked for troops from all the nearby units and merged them into bigger ones before immediately deploying them at the frontline,” Col Ndahura says.

Given the shortage of manpower, Col Ndahura was also assigned another task of being a courier of information from one unit to another. The intelligence provided about Lakwena’s plan was prolific.

Before dawn, Lakwena’s fighters started traditional singing and dancing, which was their signature practice whenever they were going to carry out an offensive. At dawn, Lakwena attacked NRA positions at the frontline. NRA soldiers too fired back. Col Ndahura said the shooting was so intense that barely anyone rested. However, none of the sides gained ground over the other.

“The fighting went on for the entire day and everyone was exhausted. We were running out of everything needed to fight. Dead and injured comrades were arriving from the front line at a shocking rate,” he remembers.

Another twist

Seeing no prospects of holding the ground, Maj Gen Rwigema decided to withdraw and reorganise.

“Bullets were flying like rain. Some of my bodyguards were hit by them and they died or were injured as we walked to deliver messages to different sections. I was supposed to tell the commanders at the front to withdraw, which meant that the enemy was going to shoot at the fleeing troops,” he says.

The NRA soldiers were to use the cover of darkness to withdraw to minimise losses. Col Ndahura says something came to his mind to give it another try rather than just fleeing from the enemy.

“I checked on the troops who were in their trenches and I gave a fire-and-move order. This order means the soldiers were to get out of their trench, stand and fire as they charged forward,” Col Ndahura said.

The first group implemented his order and another group followed, then the entire team did the same. Some of the soldiers fell to the bullets from the enemy, but the majority advanced swiftly for several minutes. Then, Col Ndahura says, they saw the enemy firing as they retreated. It energised them to move forward farther.

“What we didn’t know was that the other side were also very few and they were also planning a quick withdrawal. In the intense firing, the rebels abandoned their front and made an unplanned withdrawal,” he says.

The Corner Kilak battle left Lakwena’s key commander, Brig Eric Odwolo, dead. Lakwena’s rebels withdrew to Pajule near Kitgum District. The fight ended deep in the night.

“Everyone was too exhausted and many literally collapsed to rest that night. That decisive battle earned [Julius] Oketta, the commander of Delta Mobile Force, a promotion to the rank of Captain,” he says. “I was a sergeant. Professionally, the battle win goes to the commander.”

Much-needed tonic

The defeat of Lakwena at Corner Kilak enabled the NRA soldiers to advance to Soroti Town. Despite the role political commissars played in many battles, they were rarely considered for promotions because they weren’t seen, at least by some top commanders, as real fighters. In fact, Gen Salim Saleh had to hold a special course for the political commissars for them to get promotions.

In the same year, the army started establishing regular formations like any professional armed force. Col Ndahura and others were sent to the training school for a cadet course at Jinja. After the training, he was deployed at the Second Division based in Masindi District as the political commissar.

In 1994, Uganda was asked to contribute troops for its first peacekeeping mission to quell a civil war in Liberia. Months after the first batch was sent to Liberia, the soldiers were operating in a very stressful environment that was so humid yet they had to wear heavy gear nearly at all times. Soldiers were getting blisters all over their bodies. Since Ugandan soldiers were fresh from a civil war, they were seen by their counterparts in the peacekeeping mission with contempt despite being disciplined.

“The discipline of soldiers from some of the troop-contributing countries was terrible. Their soldiers had established families with the local women. Their camps had children. They were involved in business. Sometimes they would steal peacekeeping items and sell them off to the locals,” Col Ndahura discloses.

The commanders of some of the troop-contributing countries would accept such on grounds that it would relieve the soldiers of the stress of operating far away from home. Ugandan troops rejected that and implemented professional standards, creating a wedge between their counterparts.

Despite the discipline, Uganda was losing soldiers not because of war, but due to stress caused by being home sick.

“A homesick soldier would wake up and say he wants to go back home. You would convince him that he should wait. Then the next day, he locks himself in a room and demands that you airlift him back home by 4pm or he commits suicide,” he says. “If you don’t put him on the next flight, he shoots himself.”

Tactical brilliance

The army leadership saw political commissar tasks sorely missed in the mission. Political commissars were needed to counsel the soldiers, to ensure they didn’t veer off the ideologies of the mission and develop good relationships with all groups operating in Liberia.

Col Ndahura was chosen. Upon arrival, he found that the task went beyond the troops, but also rebels and civilians.

“The Liberian rebel groups would consume a lot of drugs that would influence their actions. We had to engage and dialogue with them when they were in that state,” he said.

The decision of the rebels forced Ugandan troops to maintain wartime preparedness at their bases by digging trenches while their counterparts relied on sandbags for protection.

“One time, the gang decided to attack our base,” he says, adding that the contingent commander, Maj Gen (Rtd) Joseph Arocha, told his troops to hide in the trenches without firing back until an order was sounded.

The gang members, who were under the influence of drugs, fired as they walked to the front without knowing that our soldiers were in their trenches.

“When the gangs were very close, Uganda troops emerged from their trenches. The rebels found themselves surrounded. They surrendered with their weapons,” he says.

When they were released, they told their colleagues that Ugandan troops had used supernatural powers to disappear or deflect bullets during the fight, only to emerge later.

The rumour quickly spread and was believed by the other gangs that they never dared to attack Ugandan troops.

On the rise

When Col Ndahura returned to Uganda, he was deployed to the Military Police as their political commissioner. In 1998, it earned him a promotion to Captain.

Another leadership opportunity appeared after senior NRA officers returned to Rwanda, leaving a shortage at the command level.

“Forty of us were selected to go for a course in Monduli in Tanzania. We were to return to fill the gap that the Rwandan commanders left. No course done in Tanzania is easy. The five months were so harsh to us, but put us in better shape,” he said.

Col Ndahura was deployed in the State House as the military assistant to the President. At the same time, he was the operations and training officer in the Special Revenue Protection Services, a unit that was established to fight smuggling and tax evasion.

Gen Kale Kayihura, then a colonel, was the overall commander and he was his second-in-command.

“We were tough on smugglers. Being cadres, we didn’t accept bribes from the smugglers. We ensured everyone paid their fair share of the taxes,” he says, adding that they would “compete among ourselves on who made the biggest seizure of smuggled goods.”

Continues next weekend