Tracy Katusiime, 22, a teacher from Wakiso District was born with sickle cell disorder. She says she takes at least two different types of medicines every day to manage the condition.

“My parents got to know my status when I was five years old. They took me to Nsambya Hospital, but it [the pain] persisted. A doctor advised my mother to take me to Mulago Hospital since I might be suffering from sickle cell disease,” she says.

When the results came out positive, her parents did not immediately reveal her status.

“They told me about it when I was in Primary Two. I thought it meant I was special. My parents would limit my playing time because back then, there was nothing like hydroxyurea to stop the pain episodes. Whenever I was playing, they would tell me not to laugh too much, and if I was crying, they would also tell me to stop crying,” she says.

New figures from the government show a growing burden of sickle cell disease (SCD), with laboratories identifying 34,729 positive cases (representing seven percent) out of 500,000 tests done in children in the last 10 years. The tests were done for children with symptoms suggestive of SCD and those whose parents carry the sickle cell trait (SCT) or have a family history of SCD.

Although global studies show that the number of children with sickle cell disease has been on the rise in sub-Saharan Africa where Uganda is located, the high incidence of seven percent reported by the Health ministry can be attributed to targeted screening.

Researchers have also attributed the rise in the number of children with SCD to a high population growth rate amid limited success in interventions to address childbearing between couples who are sickle cell trait carriers.

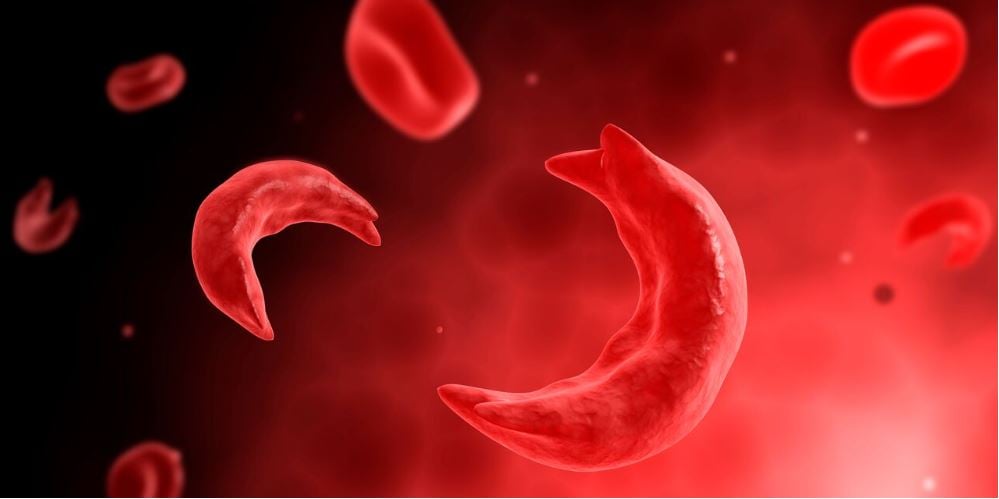

SCD is a genetic disorder affecting red blood cells, making them unable to carry oxygen around the body efficiently and is associated with several health complications and early mortality.

Dr Susan Nabadda, the commissioner for Laboratory and Diagnostic Services at the Ministry of Health (MoH), says the findings were made after they started screening newborns for the disease.

“The age of screening is from zero to six months but we go up to five years. We went to different high-burden sites and tested more than 500,000 children and the numbers of those with the disease are increasing. In 2023, we almost reached 50,000,” she explains.

The screening is being done at some 150-health facilities in high-burden districts.

“If it were possible, every newborn baby would have been screened, but we did it in a targeted way because of [limited] resources. Stepping up screening and testing services is essential in addressing the rising number of children born with the disease. The more we reach people, the more we do surveillance. It will also enable us to know where the disease is and where we should target our interventions,” Dr Nabadda adds.

Mali case

A similar strategy was employed in Mali between 2010 and 2012. The results showed that the incidence of positive cases was much lower than what has been recorded in Uganda.

A report published by ScienceDirect indicates that 2489 newborns were screened for sickle cell anaemia at the umbilical cord. Of these, only 16 had SCD. This indicates an incidence of 0.6 percent, while Uganda’s incidence of SCD is 6.9 percent.

However, the sample size in Mali (2,489) is lower than Uganda’s 500,000 and this may partly explain the variation in findings.

The health ministry says more than 80 sickle cell clinics and 10 specialised health facilities have been set up to provide care to persons living with the inherited disorder. However, Dr Ruth Namazzi, an SCD specialist at Mulago Hospital, says there is an urgent need to improve the quality and continuity of care for sickle cell warriors.

“There is a shortage of medical experts in the area of SCD management, crowding in sickle cell clinics, and lack of access to tests for monitoring the condition of the warriors on medication,” she says.

Dr Namazzi tasked the government to train all medical and clinical officers on basic SCD management so that only complicated cases are referred to Mulago Hospital and other specialised centres.

“Mulago Hospital’s sickle cell clinic runs from Monday to Friday. Some of the adult clinics run once a week. As our child patients grow to 20 years and above, they should have people (knowledgeable medical personnel) to take care of them. We will not wait for adult haematologists [to increase in number from three. We want to train available medical personnel to take care of them,” she adds.

There are reports by medical personnel and parents that some young people with SCD are falling out of care and abandoning treatment, partly because of the clinics’ operations, which they say, are not youth-friendly.

Some SCD warriors have to take medicines like hydroxyurea daily to remain healthy, yet there are reports by some activists that some areas face limited supply of the free drugs provided by the government.

Parents have to buy the drugs expensively from pharmacies while those who cannot afford are forced to leave their children to battle the excruciating pain associated with the disease.

Dr Charles Kiyaga, the head of the Sickle Cell Control Programme at the MoH, told this reporter that the drop in price of hydroxyurea, from Shs1,500 to Shs600 per capsule, is increasing its access and affordability.

“The price of hydroxyurea has dropped by 60 percent in the last two years. We are doing a lot of advocacies and trying our best to ensure that we provide free medicine in the clinics we have set up,” he says, adding, “We are still advocating with the manufacturers for the price to further go down to Shs500 or Shs400 per capsule.”

On academics

Katusiime says the disorder has affected her academic performance and the pain causes serious emotional and mental health effects. However, she notes that with the introduction of hydroxyurea, the pain episodes have significantly reduced, improving her productivity at work and general quality of life.

“I started going to Mulago Hospital clinic in 2008. By then, they would give us diclofenac and folic acid. But now, we have hydroxyurea, you can take even a year without getting crises/pain episodes,” she reveals, adding, “I am taking two hydroxyurea tablets, folic acid and multivitamins daily. I take three fansidar tables in a month. There are many medicines you have to use.”

However, she says access to hydroxyurea is still hard for people upcountry and that sensitisation is not focusing on the right people amid a lack of social support for the persons living with the disorder.

“Some people still buy hydroxyurea at Shs3,000 yet in Kampala it is Shs800. Why doesn’t the government fix the price at Shs500 to make everyone access? We are doing newborn screening for sickle cell but their main target for sensitisation is adults. Let them put more focus on young people so that they do not produce children with the disease. Let them go to schools to sensitise and screen those children before they fall into a ditch,” she advises.

National picture

Details from MoH also indicate that between 20,000 and 25,000 babies are born annually with SCD in Uganda.

Dr Jane Ruth Aceng, the health minister, said earlier that up to 70 percent to 80 percent of children with SCD die before their fifth birthday.

She also said SCD contributes 15 percent of the under-five mortality rate.

Medical doctors advise couples to undertake sickle cell tests before marriage or conception. If both parents carry the sickle cell trait, they have a high possibility of passing the disease to their child.

The 2014 National Sickle Cell Trait and Disease survey report shows that districts in the southwestern region had the lowest prevalence of the trait, being less than five percent. Eight districts had a prevalence of the trait greater than 20 percent, with the highest being Alebtong.

Dr Aceng said mid-north (Acholi and Lango), east central (Busoga, Bugweri, Bukedi and parts of Teso), and Buliisa and Bundibugyo have a trait prevalence of more than 20 percent and a disease prevalence of more than one percent.

The national prevalence for the trait is 13.3 percent while the SCD prevalence stands at 0.7 percent. Fourteen districts, including Kampala, Gulu, Lira, Jinja, Tororo, Luweero, Wakiso, Apac, Iganga, Mayuge, Buikwe, Oyam, Masaka, and Masindi contribute to 47 percent of the national disease burden.

Details for SCD in the survey report show that east central (Busoga, Bugweri, Bukedi, and parts of Teso) is leading at 1.5 percent, followed by mid-north (Acholi and Lango) at 1.3 percent, mid-eastern at 1.2 percent, north east at one percent, and central at 0.8 percent.

Kampala had a disease prevalence of 0.7 percent, both mid-western and West Nile had 0.5 percent, and south western had 0.2 percent.

“Sickle cell being a genetic disease is not curable but preventable. Therefore, more effort needs to be placed on prevention interventions. There is a lot of ignorance about SCD with many people still believing it is due to witchcraft or curses,” Dr Aceng said.

She added that the ministry’s intervention efforts are accompanied by sensitisation campaigns to create awareness.

“The ministry, working with various sickle cell NGOs, has conducted a number of awareness campaigns, especially in the high-burden districts. The ministry has also embarked on making strategic partnerships with cultural, religious, and political leaders to create awareness in communities,” she said.

About SCD

SCD is a group of inherited disorders that affect the haemoglobin, causing sickle-shaped red blood cells. Haemoglobin is the protein in the red blood cells, which carries oxygen. Healthy red blood cells are round and move easily all over the body but with SCD, the cells are hard and sticky. They are shaped like the letter C, looking like a farm tool called a sickle.

Scientists say these abnormally shaped cells clump together and cannot move easily through the blood vessels. They can get stuck in small blood vessels and block the flow of healthy oxygen-rich blood. This blockage causes pain to the victim and can also damage major organs.

Scientists say people with the trait (one sickle cell gene) do not suffer from sickle cell disease and its complications but can transmit the gene to their children. If both parents carry the trait, the risk of having children with SCD is very high and so marriage/pregnancy among carriers is discouraged.

Information from the health ministry also indicates that people with SCD usually suffer from several complications, including severe anaemia, life-threatening bacterial and malaria infections, recurrent body and bone pains, generalised organ failure, and other life-threatening conditions. These complications interfere with many aspects of the patient's life, including education, employment, and psychosocial development; with dire social and economic implications for the affected children, their families, and the country as a whole.

KEY STATISTICS

1. A total of 20,000 to 25,000 babies are born with sickle cell disease in Uganda yearly.

2. A total of 34,729 sickle-cell-positive cases found in 500,000 tests done in children in the last 10 years.

3. Uganda has 150 laboratories for sickle cell screening

4. More than 80 sickle cell clinics and 10 specialised health units caring for persons living

with SCD.

5. Shs1,500 to Shs600 per capsule now increasing affordability access

6. Up to 70 to 80 percent of children with SCD die before

their fifth birthday.

7. SCD contributes 15 percent of the under-5 mortality

REGIONAL AND GLOBAL PICTURE

A 2021 global report on SCD published in the Lancet, a scientific journal, indicates a significant variation in SCD incidence across the globe amid the growing burden of the disease worldwide.

The report, titled, Global, regional, and national prevalence and mortality burden of sickle cell disease, 2000–2021: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021, shows that in Uganda, between 500 and 1,000 babies are born with SCD per 100,000 live births. This is too high when compared to Rwanda’s 15 to 50 SCD cases per 100,000 live births.

However, in Kenya, the incidence is much higher than in Uganda, with 1,000 to 2,000 SCD cases per 100,000 live births, while Tanzania has 500-1,000 SCD cases per 100,000 live births, similar to the situation in Uganda. Elsewhere, in West Africa, in countries like Nigeria, birth incidence of SCD is as high as 2,000 to 2,595 SCD cases per 100,000 live births, one of the highest in the world.

On the other hand, in some countries like South Africa,the incidence is as low as 0 to four SCD cases per 100,000 live births. The incidence is also this low in the United States of America, Russia and Australia.

“Between 2000 and 2021, national incidence rates of SCD were relatively stable, but total births of babies with SCD increased globally by 13·7 percent to 515,000, primarily due to population growth in the Caribbean and western and central sub-Saharan Africa,” the global report reads. The researchers continued: “The number of people living with sickle cell disease globally increased by 41·4 percent from 5·46 million in 2000 to 7·74 million in 2021. We estimated 34,400 cause-specific all-age deaths globally in 2021, but the total SCD mortality burden was nearly 11-times higher at 376,000.”

“In children younger than 5 years, there were 81,100 deaths, ranking total SCD mortality as 12th across all-cause mortality estimated by the GBD in 2021,” the researchers added.