Old Girls of Namasagali College (from the early to mid-1980s) perform a creative dance at the school during its 50th anniversary in 2018. PHOTO/COURTESY/ TIMOTHY KALYEGIRA

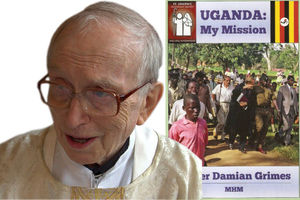

Much has been written and said about the late Fr Damien Grimes, a former headteacher of Namasagali College in Kamuli District, who died in England on September 4.

There is too much history and too many angles to compress into a single article such as this one. The question on the minds of many Ugandans is: How could a school that once electrified the country and had such a famous roster of students, have collapsed so dramatically?

Suffice to say that Namasagali College today is a sad shadow of the school that caused waves in Uganda in the 1970s and 1980s. Many outsiders, seeing pictures and video of a rundown school, have wondered how it all came to this. They imagine that Namasagali in its heyday had first-class facilities and since Fr Grimes left, it has been reduced to a rusty pile of wreckage.

The truth is that Namasagali, even in its best years, was never a five-star hotel. At its height, it produced national boxers, swimmers, creative dancers, and musicians. In the minds of most Ugandans, Namasagali was a performing arts school and it seemed that all the students ever did was dance.

What every former Namasagali teacher and student knows is that the school was not about its buildings and surroundings, but its creative and recreational spirit. The loss of this creative culture with the departure of Fr Grimes in the early 2000s, rather than the rundown buildings and overgrown grass, is what true Namasagali students find most regrettable.

New social culture

There is background to this. As relative political stability began to return to the central towns of Kampala, Jinja, and Entebbe from which most of Namasagali’s more affluent students came, parents increasingly saw little reason to send their children to Namasagali 120kms away. A new social culture, influenced by Western Europe and the United States in which parents are encouraged to indulge their children, also took root in Uganda.

Where in previous decades parents regarded boarding school as a good experience to toughen their children and prepare them for life’s later realities, parents in more recent years were more protective of their children, many buying them mobile phones and wishing schools could permit phones during the term so that their children were always a phone call away.

Where in earlier decades parents viewed the basic rice, posho, and beans as sufficient for their children, the new generation of parents almost seemed to want their children to be fed chocolate cake, ice cream, and pizza as part of their meals.

The school, which had survived and flourished during Uganda’s most difficult years in the 1970s and 1980s, now found itself overtaken by time and new preferences. Namasagali College, then, did not arrive where it is today because of mismanagement but rather this structural shift in society.

Disruption?

The way Radio Uganda was disrupted by the arrival of private radio stations 30 years ago, is the way the privatisation of the educational sector disrupted Namasagali.

Nevertheless, even with the new private elite and international schools established in Uganda since the 1990s, none is close to being the school that Namasagali was. They have much better buildings, food menus, and other facilities than Namasagali. Some even rank among the top schools in the national exams. But they don’t have the magnetic charm and buzz that made Namasagali such an exciting and controversial national name.

Apart from being schools for children of the expanded new middle class and doing well in the Uganda National Examinations Board (Uneb) exams, what else are they famous for? Nothing.

These new private schools are, at best, prestigious versions of the traditional government and church-founded schools such as Gayaza High School, Nyakasura School, Namilyango College, and others.

Like most educational institutions, they profess to cultivate not just students’ academic abilities but to develop their all-round personalities and prepare them for a future place in society. But they don’t cause waves and break new ground the way Namasagali did. Namasagali, around its core sporting and artistic culture, was formatted to make stars of its best talent, with academics at best paid lip service.

This overturning of the conventional idea of what a school is about is what separated Namasagali from its peers then and the schools that have followed since. It was the first school to put creativity and artistry at the very heart of its being and everything else coming as an add-on.

Even if the changes had not come with the opening up of private education, Namasagali always stood on precarious ground because the vision of this charming, peculiar school was conceived and stubbornly pushed through by Fr Grimes.

Only a fellow White Briton could have carried on the school’s strange culture after Fr Grimes’ departure or death. Only he could have withstood the objections to the seemingly immoral culture of the school by the church establishment in Kamuli and pressure from the Ministry of Education, as well as a cross-section of the more conservative voices in Busoga generally.

Even former students of the school would have found it next to impossible to carry on the tradition that Fr Grimes entrenched at the school.

Empires through history have arisen, fallen, and sometimes risen again in a new form. Rome became the world’s greatest empire of its time, went through a 1,400-year decay during the Middle Ages, but in the late 1,300s, now as Italy, it became the cradle of the rebirth or renaissance of Europe, paving the way for an even more glorious artistic and intellectual new era in European and world history.

There is no reason, therefore, why Namasagali as a brand name and a fond and influential memory in Ugandan history cannot in the future be revived. After all, Namasagali College itself arose in the late 1960s from the ashes of an abandoned and rusty East African Railways and Harbours ferry and railway station.

If Namasagali College is to ever be revived, it must come as a completely reinvented concept, having studied the new educational and social landscape and present a compelling new reason for parents to send their children there.

TOUGH ACT TO FOLLOW

...even with the new private elite and international schools established in Uganda since the 1990s, none is close to being the school that Namasagali was. They have much better buildings, food menus, and other facilities than Namasagali. Some even rank among the top schools in the national exams. But they don’t have the magnetic charm and buzz that made Namasagali such an exciting and controversial national name