Mr Charles Onyango-Obbo

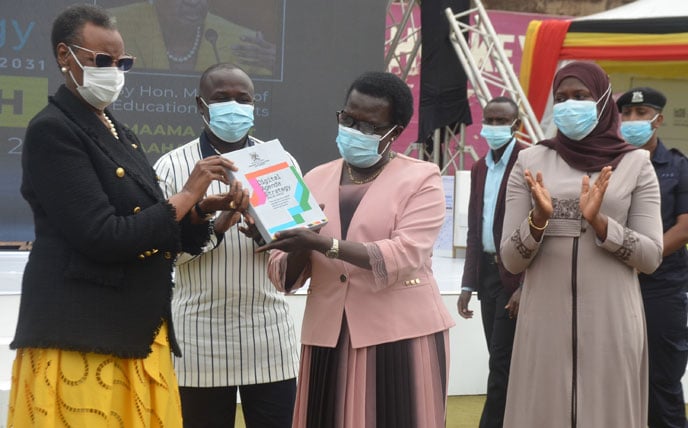

The Ministry of Education announced a decision that will allow students to carry tablets, smartphones and laptops into classes, in the hope that this will improve learners’ digital skills, teaching and learning outcomes. Until now, these had been banned or heavily restricted.

One of the most significant takes on this development was tucked away in the middle of a story in Monitorin which Filbert Baguma, the general secretary of the Uganda National Teachers’ Union while welcoming the move, urged the Uganda government to “help teachers acquire the necessary gadgets so as not to be left behind by better-resourced pupils.” This attempt to dismantle technophobia in the country’s education system, though not very revolutionary in this hyper-digital age, could be the most far-reaching reform in 28 years.

In late 1996 President Yoweri Museveni announced that universal primary education (UPE) would commence in the school year beginning January 1997. Coming in what was a trailblazing era for Museveni and the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM), it was the first such move in the last quarter of 20th century Africa. Several countries, beginning with Senegal, announced their UPEs in rapid succession after that.

The goals of UPE were laudatory, first, as a democratic political benefit to grant education access to children from poor and poorer families, who then constituted over 75 per cent of school-going kids, in the country. Secondly, to create an army of skilled citizens who would make Uganda a modern society and rich industrialised economy.

As we shall show lately, we failed spectacularly to achieve these goals. One reason for it is that, though the NRM had fought its way to power on a popular mass platform, it was focused on granting people political power (in resistance councils/local councils), not socially liberating them (with scientific and philosophical enlightenment etc.). The closest it came in this latter regard was in ideological education (partisan pro-regime propaganda teaching) and muchakamuchaka (discipline paramilitary drills).

The idea of UPE was first mooted by Democratic Party’s Paul Kawanga Ssemogerere in his manifesto, when he faced off with Museveni in the country’s first presidential election in May 1996.

Standing in a no-party election, Ssemogerere didn’t have a chance, but some of his policy positions, particularly UPE and agricultural reforms, caused a stir and early excitement for his campaign. It caught everyone, especially the NRM, by surprise. Within weeks, Museveni was offering UPE too as part of the goodies of the NRM struggle to the country, though it had not been expressly provided in his manifesto. With a louder megaphone and greater presence, soon it became his, leaving Ssemogerere complaining that his idea had been stolen.

Today, the children who started UPE in Primary One at the age of five and survived, are 32 years old. Many have had their children who have also been in UPE schools for some years now. We therefore have enough with which to evaluate their worth, and the value of the programme. According to the World Bank and UNESCO estimates, 81 per cent of children enrolled in Ugandan public primary schools could be learning poor. Learning poverty means they are not able to read and understand an age-appropriate text by age 10. Uganda’s Human Capital Index tells us that a child born in the country today will reach only 38 per cent of its potential. This is lower than the 40 per cent average for the sub-Saharan Africa region.

The collective production of over a generation of UPE Children can be measured, among other things, in our national innovation. In that regard, the last Global Innovation Index tells us that Uganda’s creativity has been declining. In 2020, it was already a lowly 114th out of 132 countries. It dropped to 119th in 2021, remained there in 2022, and fell to 121st in 2023.

Given the continuing underfunding and decay in the public education sector, poorly paid teachers who never get paid, schools in ramshackle manyattas, lessons held in classrooms flooded a foot high with water, and desolate rooms overgrown with grass and anthills, the 2024 score could be even worse. The evolution of UPE in 1996 suggests that for the NRM government, it was not a conviction issue, nor organic. It was partly a political gimmick and a DP foil. In that sense, it is not surprising that they have botched it. The admirable new technological shift, as Baguma warned, could end up being a boon for only the “better-resourced pupils”, with the children of the Museveni Era Elite able to carry tablets into classrooms where their underpaid unpaid teachers are hiding their feature phones (kabiriti) in their pockets, and their peers elsewhere not able to afford even cardboard.

Unlike UPE, the nightmare here is not that this too will fail, but that it will succeed – for a few. It would end up being just another driver of inequality.

Mr Onyango-Obbo is a journalist, writer and curator of the “Wall of Great Africans”. Twitter@cobbo3