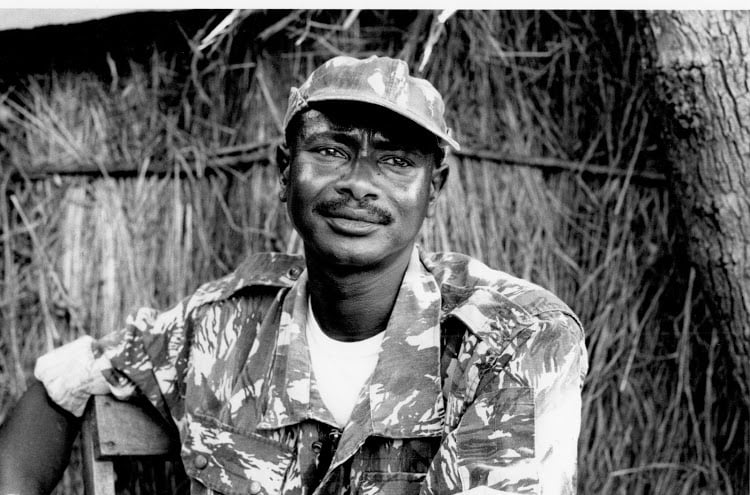

Mr Daniel K. Kalinaki

Of the few moments of regret that I carry in my heart, one relates to a moment etched indelibly in my head from over 30 years ago. It was, if memory serves me right, late 1988 or early 1989, and Mr Museveni was visiting Kamuli Boys Boarding Primary School where, the two regular readers of this column might recall, my elder brother and I had unceremoniously been dumped a few months earlier.

Mr Museveni had been president for only a couple of years, but he was still coated in star dust. In those days he travelled around the country with a blackboard and chalk, giving lectures about this or that. By dint of my city-born accent, I had been selected as one of the student ushers, so I was near the front when, in the middle of his lecture, Mr Museveni turned around from the blackboard and asked the crowd: “What is infant mortality rate?” A hush fell over the crowd of teachers, students, local officials and area natives. I quickly ran the question through my mind. I quickly figured that mortality had something to do with death. Infant and rate I knew.

So, it had to mean the rate at which infants died. I wanted to raise my hand and give the answer. I was standing at the front and, as small as I was, I was certain my hand would be seen. But my hand remained stuck by my side, weighed down by cowardly fear. “Who knows the answer,” President Museveni asked again. I tried to say the words, but they stuck like thorny seeds in my mouth. Finally, a voice from one of the adults cut through the silence, with the answer I had. “Very good,” Mr Museveni said, and continued his lecture about immunisation and whatever else his government was bent on doing.

In the many years that have passed, every time I hesitate to do something or catch myself worried about being wrong, I remember that moment and wonder what could have been. What would Museveni have done, I always asked, and how would it have altered the course of my life? I remembered that episode the other day as I watched Mr Museveni celebrate his eightieth birthday and walked down a rabbit hole of memory lane. Uganda has made so much progress in the many years that Mr Museveni has been President, and there is much for him to be proud of.

We have gone from chronic power shortages to an oversupply of electricity. Some people have made fortunes, even if millions have fallen back down the cracks over the past 20 years. Mr Museveni’s leadership, even if it might have been self-serving and driven by concerns about infection rates among his soldiers, allowed for progressive public health policies that allowed us to turn the tide against HIV and Aids. Immunisation rates are up, and the number of children that join school are much higher – even if the dropout rate is high and education outcomes are low.

We have gone from not adding sugar to our tea because it was not available in the shops, to not adding sugar to our tea because we know it is not good for our health. We could go on and on. Yet it is hard to look at Mzee Museveni, now clearly entering the evening of his life and not wonder about the things that he – almost uniquely as an individual – could have given us but has, sadly, not and perhaps won’t have the time to. Many leaders can deliver economic growth and even copy-and-paste social and infrastructure plans, but few had the political and military legroom Mr Museveni had to build a truly national army subordinate to civilian authority, an effective police force, a professional civil service, and an accountable judiciary to enforce the rule of law.

No one has wielded as much power and influence over the state and its affairs and for so long as Museveni. He had the opportunity to allow the growth of independent institutions, shape the political culture and catalyse the development of a national ethos of unity and nationalism. Some say that those very limitations would have shortened his stay in office. That is possible, and perhaps even desirable, but an alternative view is that Mr Museveni wasted many years neither being fully democratic nor fully despotic. Future generations of small boys will look back and see that he gave us many things we wanted, but denied us many of those that we really, really needed

Mr Kalinaki is a journalist and poor man’s freedom fighter.

[email protected]; @Kalinaki