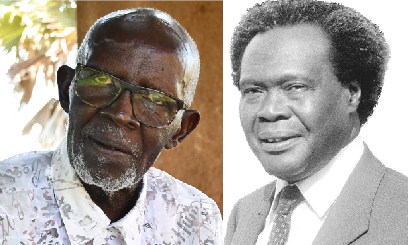

Author: Moses Khisa. PHOTO/FILE

The late American political scientist, Samuel Huntington, opened his classic book Political Order in Changing Societies with a provocative line: ‘The most important political distinction among countries concerns not their form of government but their degree of government’. A statement from 1968 that remains eerily true today.

By form of government he meant how countries are governed: democratic, authoritarian, totalitarian or other variants; how power is acquired and maintained, whether through the ballot or bullet, popular mandate or coercive machinations. The degree of government means the extent of administrative efficacy and efficiency, bureaucratic capacity and competency, whether the government exacts commanding control over both territory and people, provisioning of basic public goods and services like security and order, whether the system in place assures stability, certainty and long-term viability for both economy and society.

For Huntington, it mattered less if a country was governed under an authoritarian, dictatorial regime or, by contrast, a democratic system. Looking at countries he characterized as ‘Changing Societies’, those experiencing rapid and disruptive socioeconomic processes, what he considered critical was the extent of governmental effectiveness, not whether there was dictatorship or democracy.

For this, scholars and commentators inclined to the normative ideal of political freedom and civil rights caustically responded to Huntington’s book; to date, many consider it a kind of handbook for dictators. Today, most have made tremendous progress, while others still lag behind in state capacity and ability to broadcast power through a competent and centralised authority.

Huntington’s seminar arguments appeared just as African states were emerging out of colonial rule and consolidating their post-independence governing systems. He didn’t care much about Africa and arguably knew precious little, if anything, about the continent. His interest was in the Americas where his country, the USA, had direct territorial and geopolitical stakes. Yet, after nearly seventy years of African independence, looking back, it is a dejavu feeling.

Today’s socioeconomic terrain in most of Africa is laden with far more disruptive and potentially destructive forces, powered by huge technological fuel and rapid demographic currents, than what Huntington was concerned with in 1968. After just over two decades of independence, in 1986, the National Resistance Army (NRA) brought into town new rulers ostensibly on an ambitious mission of constructing the state and building a new nation – Uganda.

The conductor of the NRA orchestra was a relatively young, articulate and compelling figure who commanded general goodwill and respect after successfully prosecuting a guerrilla insurgency against a formidable government army, only the second case of successful guerrilla insurgency in post-independent Africa after Hissen Habre’s National Liberation Front in Chad. Looking back nearly 40 years later, it is hard to argue that Uganda’s degree of government today is fundamentally better than it was in 1986, that the state is more competent and effective.

To be sure, there is no insecurity in Kampala of the type where gangs and warlords control different parts of the city as was the case following the Okello's’ coup in July 1985, but we have violent crime and runaway criminality in different stripes – Kampala’s streets aren’t exactly safe. The Police Force, security and intelligence agencies are inept, corrupt and wildly incompetent. Their resources and best work reserved mostly for the political cause of securing the rulers’ hold on power.

What is more, much of the insecurity and related problems of 1983-85, including economic decay, were largely fueled by the same group fighting the government of the day: the NRA guerillas. With hindsight then, given where we are today, a country characterised by pervasive and entrenched official corruption, a ruling class laser-focused on personal and family enrichment than the wider public good, it is fair to say that 1986 was a power-grab project of personal aggrandisement by a small cabal.

Mr Museveni with a knack for long, winding and rather paternalistic lectures about the history of Africa knew all too well in 1986 that it was a herculean task building a strong and effective government. The colonial state and government inherited at independence was never intended as an effective and efficient system in the service of Ugandans; from the start to the end it was a skeletal, minimalist and thinly crafted apparatus for extraction and to primarily serve the imperial interests of Britain.

Sadly today, the state and government Mr. Museveni presides over is more impoverished in its capacity to meet the needs and aspirations of Ugandans than the colonial version Milton Obote took over in 1962.