Emilly C. Maractho (PhD)

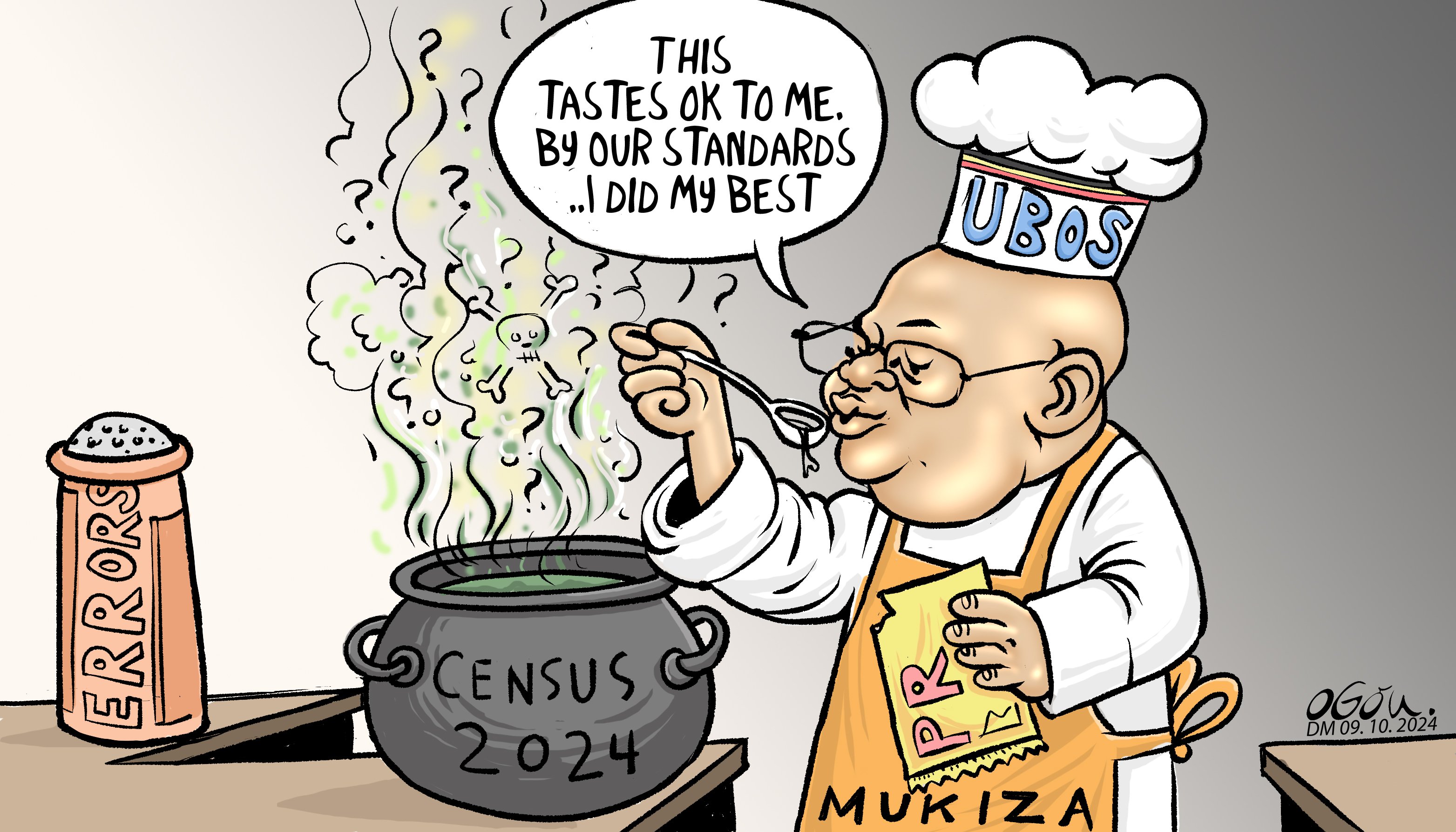

The last few years have been difficult for the leadership at Uganda Bureau of Statistics (Ubos), judging by media reports. The last week has been difficult due to errors that took the public moments to recognise that their army of experts, internal and external, did not see.

It will be difficult to explain that people have been fighting Dr. Mukiza from days before the census that is why this is a big deal. The errors, human as they are, can be considered grave. It is difficult to believe that 12 external reviewers did not ask questions of the data, and the Ubos team could not see that something was not sitting well too.

I come from a profession where sometimes, despite our best efforts, and an entire process of looking over and over, through various processes, one or two mistakes will slip through, sometimes, often.

As a researcher, I know the pains of trying not to allow that small allowable margin of error to appear and sometimes, realizing too late that one tiny thing is staring you in the face. So, I am approaching this article with as much compassion as is possible. Once this column was published with an error, a wrong word, and a reader wrote and lectured me about the importance of not allowing a mistake to slip through, one word.

As such, I sympathize with the Ubos people and will say, it is plausible that you have ten years to prepare and publish a single report, yet some not forgivable errors show up and very publicly. It is fortunate that you are not a newspaper or someone would already be running to court, demanding apologies over what qualifies for a human error. And sometimes they know, it is not even wrong, the information is factual but must accuse you of bias.

Yet, to say the error was in the middle, therefore difficult to detect, in an exercise like a national census is inexcusable. Data speaks, and sometimes all it is telling us is that something is wrong.Credibility, is the most important aspect of research, that is why so much is done to ensure the entire process, not just the results are okay. Like a national election, the credibility speaks alot to the results and usability of the output.

Ubos has done its part to explain away the errors and most researchers will appreciate that it is reasonable. But this is also a national census. Unlike the elections that happens every five years, this is a once a decade exercise. The institution is not disbanded after every census. Literally, they have ten years to prepare for the next one. Yet, from the very process of data collection, it was clear that the institution was ill prepared. If you put all the pieces together, the reports during the actual data collection, it would have taken a miracle for the end to be flawless.

With all the technology deployed, we managed to make serious data errors that we are dismissing as simple human errors. The problem is, it casts doubt on the whole exercise. Whereas the rest of the data could arguably be considered accurate, the perception that they are not will affect us beyond our borders. This is quite frankly, disconcerting and disgraceful.

There are some responsibility centres that naturally demand more of us. A national census is one of those, along with a national election. The preparation of these demand sweat and tears, not to be explained away. Because they are periodical with high stakes, credibility is premium. One cannot joke around the numbers because errors will be difficult to explain. The moment people begin to suspect some sort of fixing gone wrong in our national data, we are finished.

There are many reasons to worry about the credibility of the data. There were many questions with no means of verification. There is little to do in linking the data being collected with existing data of a particular respondent. If I say I own one house or bicycle, the enumerator has no means to verify. The information may not be factual because people rarely say the truth.

For that reason, the only crucial part one needed to get absolutely right is the population, to give us hope that waiting ten years and spending so much to do this is not a waste of energy and other resources.

Atleast they can inform national planning where information on population is crucial.

Imagine that your national planning authority makes planning decisions for your district on wrong data, and ministry of finance allocates your district resources based on wrong figures, and the national revenue projection is based on wrong income statistics. It is a never-ending cycle of strategies based on faulty information giving bad results.

The problem is much bigger. We sometimes imagine that we can be part of a whole and succeed when the rest of the parts are failing. That is always far from the truth. The beauty is, it is early and these errors detected can be corrected.

Ms Maractho (PhD) is an academic.

Email: [email protected]