Prime

Selective Outrage: The crisis of Ugandan activism

Anthony Natif

What you need to know:

Activists should be rooted in ideology and not run with the popular wind and only align with what’s en-vogue. We shouldn’t pick and choose if we are for truth, justice or freedom.

In many public opinion spaces, there’s been conspicuous silence about the arrest of Tik Toker Ibrahim Musana, dubbed Pressure 247. Despite obvious provocation to speak, various activists, experts, and polemicists have caught a curious case of collective aphasia. For now, what were previously hot fires have begotten cold ashes. Dear friends and comrades for whom I have the most respect, are suddenly enthralled by the words of caution by those in power.

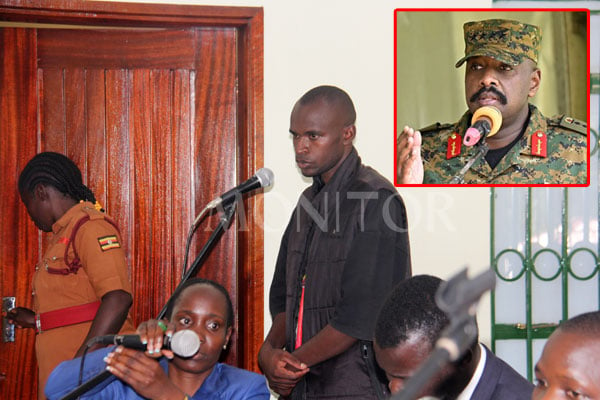

Musana was arrested, detained, and charged on February 17, 2024, for defamation, hate speech, and incitement of violence among others. Among those supposedly offended by his despicable and disgusting videos are the President, the Kabaka, and “Full Figure”. Among his many preposterous claims, Musana suggests that he is the rightful heir to the Kingdom’s throne; making it obvious that he deserves to be in a psychiatric ward and not a police cell. But my concern is not a moral judgment of character but rather the conspicuous absence of our comrades in the human rights world with Musana’s case being a typical example of the activist dilemmas of our times. This is a clear case of afront of freedom of speech that usually gets activists riled up. When beckoned to call foul play, activists chose to swallow the whistle.

If the project of the contemporary activist is to hold power to account, we must then reflect on the conceptualisation of power. The concept is defined narrowly with sights only at State power. This narrow conceptualisation may be a function of the lack of an ideological awareness or lens through which to view the world. If the masses of people in the global south are categorised as working class for the ideologue of yesteryear, for today’s activists they are the “powerless poor”, incessantly researched upon, and targeted to receive poverty alleviation funds, a myriad of lectures and no voice.

French philosopher Michel Foucault conceptualises power as diffuse rather than concentrated, embodied and enacted rather than possessed, discursive rather than purely coercive, and constitutes agents rather than being deployed by them. Consequently, the capillaries of power are diffused in many institutions away from the state among them family, cultural, social, and economic.

Buganda has a form of what Ali Mazrui defined for Tanzania as Tanzaphilia. For Mazrui, it’s neither a disease nor an exotic flower. It is a political phenomenon. A romantic spell which Tanzania ( in our case Buganda) casts on all those closely associated with her. Cultural institutions have “power” that they may exercise not through arrest like the state but through other seemingly innocuous elements that are intrinsic to all systems of domination and to the means by which those systems are confirmed or deconstructed.

This Musana episode is one of the rare occasions where the current Kabakaship demonstrated that they can flex state muscle to correct a perceived wrong. Where they had a Mukajanga in the late 1800s, now they have a Tom Magambo in the State security apparatus. It looks out of character for a Kabaka, the first, in Buganda’s nearly 500-year storied existence to not wield political power. He has navigated the rough waters of this uncharted frontier by maintaining a dignified silence about even the most heinous provocations. He wields a silent power.

The greatness of human rights activists is supposed to be in our consistent, principled, and committed stand for human values devoid of favor or prejudice. For we are not self-seeking politicians that run by the fad and most pragmatic agenda of the day; for whom compromise and expediency are most important. For the example of Musana elucidates the dilemmas of our selective activism/ amnesia on whose rights we can pick to defend.

If Musana is a witch, let him be tried under due process, and let us support that effort. We defended Stella Nyanzi for the same reason, only that her opponent then was the behemoth State which is convenient for critique. It has embedded with it, limits known to all of us like the Constitution, but what about those institutions that elude critique under ambiguous but very powerful structures, like the family that has been a source of so much abuse, torment, and spite for queer folks?

The right to free expression is one of the most precious things in life. A life without free expression is just marginally better than death. This is not to say that some speech isn’t harmful, it’s that trying to reign it in causes greater harm. Laudable efforts to police speech can be used as channels to oppress critics.

Activists should be rooted in ideology and not run with the popular wind and only align with what’s en-vogue. We shouldn’t pick and choose if we are for truth, justice or freedom. We should demand for freedom or death.

Mr Anthony Natif, Team Lead-Public Square.