Prime

Which is more important, education or motivation?

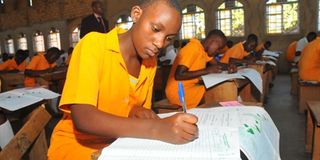

Students sit for S4 national exams. There is constant emphasis in Uganda on scoring highly in term tests and national exams. FILE PHOTO

What you need to know:

Low productivity. With the over-emphasis on academic qualifications and work experience, the question of motivation has not been addressed and yet here is one of Uganda’s major crises. It’s, therefore, no surprise that Uganda has one of the lowest levels of productivity in the eastern Africa region, writes Timothy Kalyegira.

There is constant emphasis in Uganda on scoring highly in term of tests and national exams. The requirement of good academic qualifications continues to grow.

For those with higher incomes, their children are enrolled in international schools in Kampala or top national schools in the different towns under the belief that this will increase their prospects for success in life.

If we were to go by the amount of effort, time and resources put into the education of the society, Uganda should by now be one of Africa’s most advanced countries.

Uganda should by now be at about the same economic level of development as a Malaysia or Turkey.

What we have instead is a country with very low levels of work and productivity. Virtually every major road, bridge and other public works project is now being undertaken by the Chinese, South Koreans or Japanese.

Roads in towns and municipalities that should have been built or repaired by the town council or at least Ugandan companies are now also being worked on by the Chinese.

It is hard to see what the ministry of Works still does in Uganda.

Passive, unmotivated soul

Whether it is MPs who earn more than Shs20 million a month to domestic workers, corporate executives in relatively well-paying positions, the Ugandan is a passive, unmotivated soul.

Even on the very popular social media networks such as Facebook and Twitter, most users can barely find the energy to click the like or share buttons on new posts or photos they see and enjoy.

And so, we have a situation where an unmotivated, disinterested office worker when the boss is not watching turns to Facebook and scroll through his or her status updates, but in the same bland, barely interested state of mind.

Visit the many boutiques, kiosks, supermarkets, grocery shops, restaurants and other small businesses operated by Ugandans, private businesses started by and of direct personal benefit to them, the same lethargy and lack of enthusiasm is noticeable.

One would have expected that the opening up of the economy to private investment would have released the energy to create a vibrant society. Little of that has happened.

Competition between companies and individuals in all industries in theory should have been the incentive for a company or employees, driven by fear if not by anything else, to work harder and put their hearts into their work.

Instead, the level of incompetence has remained roughly the same for most companies. There is slightly more systematic desk work in European-owned or European-headed companies and NGOs.

But it is not fundamentally something that could be described as real, inner motivation and conviction.

The only areas in life that seem to stir up real passion are European football league matches, for the women, television drama series and for men and women, music concerts.

Work, though, is something done reluctantly and resentfully.

With the over-emphasis on academic qualifications and work experience, the question of motivation has not been addressed and yet here is one of Uganda’s major crises.

It’s, therefore, no surprise that Uganda has one of the lowest levels of productivity in the eastern Africa region. One report says Ugandans have only two per cent of the productivity of the Chinese.

In recent months, Kampala traders have been complaining about being pushed out of business by Chinese traders. They say the Chinese undercut them in price and other tactics.

Given the fact that Ugandans are only two per cent as productive as Chinese, we might have to look for the explanation for the Chinese’s growing dominance in Ugandan retail trade elsewhere.

As the national spirit and sense of motivation remain this low, foreign companies are now taking over the rebuilding and the expansion of the infrastructure, revival of old factories and hotels and setting up new services.

The way the tourism industry in the Bahamas and Barbados is more or less run by Americans and Britons, the Uganda tourism and hotel industry will eventually also come to be sustained by Americans and Europeans.

They are highly motivated people. We don’t hear them appeal for help from the government. They don’t even take part in Uganda’s political process.

They face the same challenges and frustrating lack of institutional coherence as we all face.

But they just get on with what has to be done. For years Ugandans have lamented at the slow dying of Jinja and other towns. Over the last 15 years, Europeans have quietly and steadily been infusing life into Jinja.

They started by setting up whitewater rafting sites and camps, then established lodges along the River Nile and now have started setting up cafes and shops along Main Street.

In Fort Portal, the same thing is happening. Europeans are going beyond praising the beauty of the town and setting up lodges around the volcanic crater lakes on its outskirts.

If in a national exam I am asked “What is the capital city of Uganda?” and I write “Kampala”, I will have stated the correct answer.

If the rest of the exam questions are this type, set-piece question and answer that seek to see how much I can recall of what I learnt in class, I will keep passing exams and one day graduate with a university degree.

One day, a European will arrive in Uganda as a tourist or social work volunteer. That European will travel around the country or on foot within the town where he resides.

He will create in his house a museum or gallery with a collection of Ugandan cultural artefacts. He will create a Facebook page with regular information on Uganda or that town.

That European will have gone beyond exam knowledge and in the end will cause a difference that our student who simply passed exams by rote knowledge cannot do.

It is high time companies and the civil service began to test for or require motivation as a key consideration on their job recruitment.