Prime

How Obote fell out with Buganda over lost counties

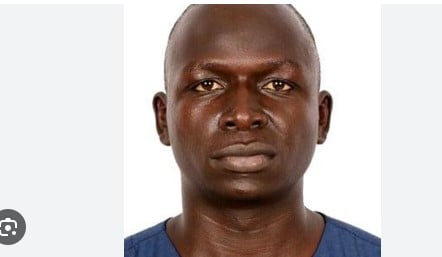

Former president Milton Obote and wife Miria at their wedding. According to Astles, Obote married a Muganda to please the Baganda who were increasingly becoming hostile to his leadership as prime minister. COURTESY PHOTO

“ However, the fighting qualities of the Bunyoro, which no doubt prevented Egyptian forces reaching Kampala, were certainly a match even for Emin Pasha who was unable to get an army through their kingdom when he was trying to reach Kampala on a mission for

He was pursuing the rebel, Nur Aga, who had defied Gordon’s orders and marched into the kingdom of Buganda with 300 Nubian troops to annex it for Egypt. Instead, he had to take the long route through Acholi towards Mt Elgon in the east. When he finally managed some years later to see Kabalega and asked for permission to pass through his kingdom for the short route to Buganda to see King Mutesa 1 on Gordon’s behalf, the audience he had with the great ruler was not an easy one. But permission was given.

Interestingly, the language spoken by the Omukama and his courtiers was Arabic and showed the long Arab connection with the area. Emin Pasha was himself eventually murdered in 1892 by aggrieved slave traders who cut his throat and severed the head completely and paraded it as a warning to others who were trying to stop the slave trading. It is difficult to believe that all this had happened less than a 100 years ago.

Kabalega continued to resist any settlement by foreigners and was furious when his distant relative, Mutesa 1, and later, Mwanga, who succeeded him, allowed missionaries into Buganda, followed by British administrators. He rightly accused them of doing so as a means of getting guns with which to attack his kingdom.

The battles towards the end of the century were fierce and the British could not make the kingdom of Bunyoro part of their administered territory until they brought in more troops from India and used massive armed support from the Baganda. Kabalega’s guerrillas had by this time been joined by Kabaka Mwanga who had escaped from Buganda following religious disturbances and pressure from the British.

Bunyoro-Buganda conflict

Kabalega, fighting to the last, was betrayed by one of the Kabaka’s attendants and he and Mwanga were captured in the tribal lands of Lango. I was shown the actual place by Dr Obote and it is still revered by the people there who can describe from folklore how Kabalega and Mwanga fought it out with the troops of Lt Colonel Evatt in the early hours of the morning in April 1899.

Obote’s grandfather had been a guerrilla fighter with Kabaka Mwanga and Omukama Kabalega and I spent most of the Sunday when Obote’s first born son, Akaki, was being named at a ceremony in Lango, listening to the tribal elders as they proudly described their resistance to British influence, which had threatened their freedom. Until then, I had no idea that such a large colonial war had been going on and seemingly it did not end until just before World War I. The Langi are rightly proud of their inheritance and believe that they did more than any other Ugandan tribe in the fight for freedom. They also believe that the Baganda deliberately betrayed Kabaka Mwanga when he fought for the same cause, and thus betrayed not only Bunyoro and its king but indirectly their own tribe in the fight against foreign domination.

I was told that both kings in the dawn fight in Lango put up a tremendous resistance and shot many of their opponents. Mwanga was badly wounded with one arm slashed by a sabre and the right arm almost severed by a bullet. Dr Cook, the missionary doctor whom I visited in my youth, told me that he had dressed Mwanga’s arm at his Mengo hospital and within minutes, Mwanga had ripped off the bandages and was pulling out the stitches with his teeth, shouting in Arabic that he wanted no treatment from the white oppressors. Only the prompt action of the Muganda chief, [Semei] Kakungulu, prevented Mwanga losing his arm.

Kakungulu was a British agent at the time, having previously been nominated by Kabaka Mwanga to lead an army of Baganda to fight beside the British to break the Omukama’s resistance to British rule. Kabaka Mwanga later changed sides. Kakungulu died many years later, an embittered man, accusing the British administration of failing to keep a promise to make him the Kabaka of Buganda as a reward for his faithful service in leading the Baganda in the war against Bunyoro and helping Lt Col Evatt to capture Kabaka Mwanga and Omukama Kabalega.

The result of all this fighting was that the Baganda were given vast tracts of Bunyoro land as a reward for their services to the British forces (their ‘thirty pieces of silver’) which, of course, promptly went into the hands of the great chiefs of the day, including Kakungulu. It was this valuable land that became known as the ‘lost counties’ and the Bunyoro wanted it back.

Acholi connection

So here we had Obote, whose own ancestors had taken part in the guerrilla war against the ‘colonials’, now made responsible, as a result of decisions taken at the London Conference in 1961, for seeing that there would be a fair plebiscite on whether the people wanted the ‘lost counties’ returned to the kingdom of Bunyoro. It was to be a simple matter with all those living in the counties of Buyaga and Bugangaizi voting ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

As the Baganda had never bothered to settle on the lands, it was obvious that the residents, all Bunyoro, would opt to go back to their kingdom. Although this procedure had been decided by the agreement between the Baganda and Ugandan political parties in London, it is not surprising that the Baganda were not happy about it and there emerged a movement to prevent the land returning to the Bunyoro. Loosely, the movement was called ‘The case of the Lost Counties’ but to those of us in the intelligence service of the country, it was known as ‘The Ndaiga Issue’.

Ndaiga is a small village overlooking the south-west corner of Lake Mobutu Sese-Seko in the county of Buyaga. For years, the Kabaka had hunted in the area; he had a special love for its open spaces and the beautiful scenery of hills and far¬ off mountains. He was not prepared to let it go, vote or no vote, and after he had become the president of Uganda, he was involved in an ugly incident in the market place when he shot a Ndaiga resident with his hunting rifle.

This was to give Obote, who was now prime minister, considerable trouble and while he was struggling to keep tempers down, King Freddie [Mutebi] raised his own militant force that in the end, contributed to his downfall. This force was called ‘an army for Ndaiga’ and in order to raise it, the Baganda started to recruit ex-soldiers from World War II. These men were assembled daily and taken by lorry to Ndaiga where they started to parade in the streets with ominous slogans that they would overthrow Obote. This led to a most serious incident called ‘The Nakulabye Massacre’.

Nakulabye is situated just outside Kampala city and it was here that most of the veterans waited for transport to take them to Ndaiga, and a very unruly lot they were. Late one afternoon, after some of them had tried to take food by force from the nearby market, fighting broke out. The police were called but were instantly stoned and the veterans then set fire to market stalls. Next on the scene were the fire brigade who were attacked by a fast growing mob shouting slogans about the ‘Lost Counties’.

Many of the fire brigade were badly beaten and the uproar only ceased when further reinforcements from the police special force drove into the area and in self-defence, opened fire. At least five civilians were killed and two policemen seriously injured.

Later this incident was described as a massacre caused by the prime minister’s army and the real reasons for the uproar were conveniently forgotten. I was on duty that night and it was hours after the riot had been put down by the police under the command of Inspector General Oryema that Col Idi Amin reported for duty to the prime minister. He was told sharply by Obote that the army was not required either at the scene or for any patrols in the area. Amin was furious but Obote wanted no more bloodshed. My own opinion is that many more lives would have been lost in the aftermath of the veterans’ stupid behaviour.

Chaos in Ndaiga

But a new threat had been added to the peace of the country because these old ex-soldiers were a menace to public order. They were unemployed and landless and the real intention of the Kabaka in transferring them to Ndaiga was that they could fraudulently cast votes in favour of retaining the county for their king. They would be able to do this despite having no residential qualifications because the elections would be supervised by the area chiefs who were Baganda civil servants.

Ndaiga was also fast becoming a dangerous and violent place for the Bunyoro who lived there and their houses were being set alight in the darkness with subsequent loss of life. At the same time, the Baganda were claiming that they were powerful in the area and that Ndaiga had become a township. King Freddie gave credence to the claim by living there and insisting that his government, by virtue of his own residence, was also present.

The members of the government secretly were furious because living in the bush did not appeal to them as it did to the Kabaka who loved hunting. Nevertheless, the Kabaka had now aligned his two million subjects behind him over the ‘lost counties’ issue. Obote continued to struggle with the issues but he was finding it difficult to promote prosperity in the country at the speed he wanted while this sore continued to fester.

Soon it became impossible to get reliable information from Ndaiga area because the temper of the veterans was unpredictable and agents sent in were not seen again. I knew the country well, having hunted Cape buffalo there in past years, and was given the job of penetrating Ndaiga to see what was going on.

When I got there, I found that the Baganda report of the enlarged township was a fraud and that all the funds collected for its development, including money reallocated from building schools and hospitals in Buganda, had been diverted into the hands of a few prominent Baganda. It was, as Obote had suspected, a huge confidence trick at the expense of the nation.

Even the opposition party in Uganda’s parliament had caused an uproar by accusing Obote of letting the Baganda get away with it. They were particularly angry that the Baganda had misappropriated Ndaiga funds in order to pay the debts of a very prominent Muganda who was being blackmailed over his alleged association with Christine Keeler, who had gained notoriety in the world press at the time for her part in a major political scandal in England.

When I returned from Ndaiga, Obote came to my film projection room in the television building, on a Sunday afternoon when few people were about, escorted by Jeremiah Lucas Opira of the General Service Unit and bringing with him some of his trusted ministers and staff. The photographs and film I had brought back clearly exposed the theft of the development funds.

Obote was visibly upset by what he saw. He genuinely felt that he had been betrayed by his president and, worse still, that the ordinary people were being robbed. He was now satisfied that there were no grounds for making an exception of Ndaiga and that the plebiscite should go ahead, leaving it to the people to decide whether they would remain in the kingdom of Buganda or return to the kingdom of Bunyoro. The ballot, when finally held, was supervised by members of the British government and so was a fair one.

In the area where the Baganda were prominent, the majority voted to remain in that kingdom but in the rest of the area, the population voted to return to the Bunyoro, whose claim to have lost the land because they had fought to preserve their freedom was not in dispute. All the same, the Baganda were furious and a photograph was composed showing Obote sitting beside a baboon which sold in hundreds and was prominently displayed in their homes. It was an evil picture and those behind it were pure tribalists with no thought for the unity of the country.

Obote still insisted, against the advice of his cabinet, that without Buganda, Uganda as a whole would be at a disadvantage on the road to prosperity. He decided to marry a Muganda woman and show that like his forefathers, who had fought with Kabaka Mwanga and Omukama Kabalega, he was an ally of the tribe. And no doubt the idea of the marriage came from his Baganda advisers.

Miria [Kalule], the woman he was to marry, had been trained as a secretary. Her father, whom I knew well, was a clerk in my ministry. He was a softly spoken, pious, hardworking man with a devoted family and they lived in a cottage, a few miles out of Kampala on the main road to Bombo. He did not come from one of the well-known great feudal families who were used to having most things handed to them on a plate and he had done all the work in the house and garden himself.

He also worked hard to get the best education for his children. When I knew him before independence, he cycled to work and years later when his daughter could afford to give him a car and a bigger house, he refused and remained unchanged, still cycling to work.

If Obote had hoped that his wedding in Namirembe Cathedral would help reconcile the Baganda to a unitary state, he was disappointed. They protested vociferously about this northerner marrying in their cathedral and about the VIP coverage he had received.

This infuriated me because I was responsible for the television coverage and Obote had given me strict instructions that there must be no waste of public money. Only one 16mm Bolex camera had been used in the cathedral and the reception in Lugogo stadium was not covered at all, again on Obote’s orders, and this in a world where television covered every public movement of African heads of state.

Conflict grows

During the short time the country had been independent, Obote had certainly not picked any quarrels with the Baganda yet they could not contain their annoyance, and from that day, they referred to that “enormously expensive” wedding.

It was clear that everything Obote was trying to do to unite Uganda was being sabotaged by some powerful Baganda traditionalists despite having appointed most of their people in his government. The more they attacked him, the closer I moved to his camp, which was painful for me as I admired the Baganda. I was one of the few people who visited his home from time to time, and it would be difficult to find a gentler family. He was devoted to them and unlike many African men, he was not a bully in the home.

When ministers and others are forever seeking personal publicity to build up a following, it is essential for the leader to be tough. But the deep hostility towards Obote meant it was not long before the traditional savagery of Buganda resurfaced and some Baganda started plotting his death. I discovered one plot myself and others must have done the same as secrets are hard to keep in Africa. When I was taken to Obote to explain the plot, I had discovered he was angry and insisted that it was all rumour. He could not believe that anyone would want to kill a prime minister when a country had just received its independence from colonial domination.

He refused extra security and all we managed to do, without his knowledge, was to remove some cooks from State House kitchens. But the plots were real enough and I had been meeting some of the plotters at least once a week without knowing that they were the men responsible, which is one reason why I am no longer surprised by anything that happens in Africa.”

Extracted by Sarah Aanyu

Continues tomorrow