Uganda House in London. A report of the Auditor General for the period ending June 2023 says the state of the buildings in question do not reflect a good image of the country. PHOTO | FILE

The five-day introspection meeting of Uganda’s ambassadors abroad kicks off today at the Civil Service College in Jinja amid a turn of bad optics that have put the once coveted Foreign Service on the spot.

The meeting under the theme ‘Strengthening Governance and Performance of the Foreign Service for National Development’ is aimed to, among others, facilitate peer-to-peer knowledge sharing, appraise the ambassadors on government priorities and policies, and agreeing on the effective and efficient approaches for promotion of economic and commercial diplomacy.

With only one career ambassador—who has grown through the ranks, and is currently the Head of Mission in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Mr Isaac Ssebulime—in attendance, the others are joiners or political appointees, which leaves question marks on the peer-to-peer knowledge sharing.

Officially, ambassadors’ work around the world is cut out: They represent the country politically and lobby for investment, trade, and tourism. Differences in bilateral relations and the peculiar nature of partnership with a country may inform a President’s choice of who to deploy as an ambassador. In Uganda’s case, there seems to be no formula.

“We have qualified ambassadors languishing at the ministry’s headquarters in Kampala, while many of those posted abroad have not been changed for years as is the practice. This rotational practice is good and checks on abuse of powers,” Shadow Foreign Affairs Minister Muwada Nkunyingi told Daily Monitor.

This means one should join on merit and rise through the ranks from a foreign service officer (third secretary), second secretary, first secretary, counsellor, and minister counsellor to become an ambassador; picking up vast knowledge through deployment at different desks needed for negotiation and presentation skills.

On average it takes a career diplomat about 18 years of technical service to rise to the level of ambassador.

Even for lower and mid-level ranks, peer-to-peer knowledge sharing is fast fading.

Once upon a time, the benchmark for joining Foreign Service was a university upper second degree but the Ministry of Public Service, about 10 years ago, smuggled in a scheme of other terms of service like contracts (disguised to accommodate blue letter appointments, particularly from State House) at technical levels for people who do not meet this minimum.

“Even worse, when these appointments happen, they would be counted against the standard establishment, reducing the positions for the career officers. After some time, this began to affect promotions of the career staff because they would have to compete among themselves for the remaining positions through interviews while contract people demanded automatic promotions, which they are now being given just by change of contract,” one diplomat reminisced of the good old days.

Conversely, the ambassador’s conclave comes at a time when the country’s Foreign Service has been marred by a spate of diplomatic blunders, infighting over meagre resources, and low working morale, particularly among mid-level career diplomats, some of whom have not been promoted in more than a decade.

This is because the human resource pipeline is clogged by the continued staffing of relatives of the politically connected, loyal cadres, and intelligence operatives.

Following the eviction of Ambassador Joy Ruth Acheng from Ottawa, plans are afoot to reassign her as High Commissioner to Canberra, Australia. In Ottawa, she will be replaced by a son of a former minister. He, and his wife, also daughter to a former prime minister, deployed as the First Secretary, only joined the Foreign Service last year.

Joy Ruth Acheng, who has been expelled by Canada

Laughable mess

The fallout is not only abroad. Inside the Ministry of Foreign Affairs headquarters in Kampala, relations are fraught between the minister, Gen Jeje Odongo, and his deputy Okello Oryem, and on the other hand, Gen Odongo and Permanent Secretary Vincent Bagiire. This state of affairs has left many staff apprehensive.

However, the bad optics took a turn this week with the Canadian government throwing out Ms Acheng as Uganda’s High Commissioner in Ottawa over uncouth behaviour.

The scandal came against the backdrop of the ministry contending with revelations in July by this newspaper that senior officials sanctioned operations of a casino business at Uganda’s consulate in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), in contravention of the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations that sets out the framework for establishment, maintenance, and termination of diplomatic relations between states.

Uganda’s foreign spy agency, the External Security Organisation, is currently looking into the casino matter, while several individuals involved have since recorded statements with police’s Criminal Investigations Directorate.

Consul General Henry Mayega has since been recalled to the ministry’s headquarters for consultations.

While these diplomatic gaffes are not entirely new nor peculiar to Uganda, in Uganda’s Foreign Service they have become a norm while the perpetrators usually go away with their sins or get a slap on the wrist.

Whether the Australians will take in Ms Acheng remains to be seen given that Western countries usually compare notes on due diligence on foreign diplomats.

Case in point, in 2016, Canadian authorities rejected the cross-transfer of a senior diplomat from next door at the Mission in New York, where the said diplomat had been thrown out on domestic violence charges.

Uganda’s Consul General to UAE Henry Mayega, who has been recalled.

Before being named High Commissioner in 2017, Ambassador Acheng, a Uganda People’s Congress stalwart, had earlier in 2015 pledged to support President Museveni without officially crossing to the ruling NRM party. Then in 2016, she was named State Minister for Fisheries during the Cabinet reshuffle that year but her name was later withdrawn.

For the Canadians, according to diplomatic sources, the waiver of Ambassador Acheng’s diplomatic credentials and ultimate designation as persona non-grata—meaning the said person is unwelcome or unacceptable—was after months of patiently waiting, either for her to reform or the Ugandan government to withdraw her.

Months earlier, sources indicated that the Canadian authorities penned a seven-page diplomatic protest note to her superiors in Kampala, asking, diplomatically, for her removal, which warnings the Kampala regime either missed or deliberately ignored.

The alleged misbehaviour included, among others, those of her adult children, her turning the embassy into the ruling NRM outpost, confrontations with the opposition National Unity Platform supporters in the streets and closed-door meetings, and the February razing down of the official residence, a stucco house, which had heritage protection under Canadian laws to be replaced by an eight-storied structure in the upscale Rockcliffe Park neighbourhood.

The unapproved demolition, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation—CBC—first reported on February 9, infuriated both area residents and local authorities who mulled legal action against the construction company contracted.

While the embassy enjoys diplomatic immunity from such legal action under the 1961 Vienna Convention, for Ambassador Acheng. this was another dent.

Retired ambassador Harold Acemah described the current meltdown as “a tragedy of monumental proportions for MOFA and Uganda.”

“What is happening has done enormous damage to the national image and national prestige of Uganda. As I have argued many times, Uganda’s Diplomatic Service should be staffed by career diplomats, especially ambassadors and high commissioners accredited to our embassies and high commissions abroad” he said.

Diplomatic melt down

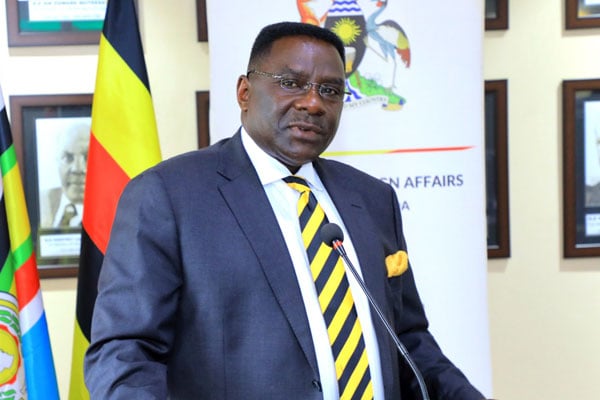

State Minister for International Affairs Henry Okello Oryem in an interview with NTV, a sister station to this newspaper, on Tuesday regretted the back-to-back incidents in Ottawa and Dubai.

“We should not judge Acheng by what you saw on social media of her being on the streets confronting the NUP. She should not be judged by that. She should be judged by what might have happened the whole time,” Mr Oryem said, adding: “Acheng will be considered for deployment somewhere else, at the discretion of the President.”

Mr Nkunyingi, however, maintained that the continued appointment of particularly NRM election losers as ambassadors is an extension of the impunity normalised locally.

“When appointed they tend to feel that they are responsible to the appointing authority more than to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs which explains that sometimes they are constrained on how to respond to their behaviours,” Mr Nkunyingi noted in an interview last Friday.

The Ottawa Mission itself had for long been a spectacle. The mission had only one career Foreign Service officer while the rest are appointees from here and there, including a senior minister’s husband and a son to another Cabinet minister and NRM historical. The said son has been in the post for nearly a decade, going against the routine of rotating diplomatic staff. Attempts to recall him resulted in grave implications for the diplomat who did so.

Whereas the appointment of ambassadors is a prerogative of the President, critics argue that the country is reaping from President Museveni’s continued turning of the once coveted Foreign Service as a dumping ground for loyal cadres and political rejects as ambassadors.

The result has been an endless supply of stories and complaints of heightened tensions and mutual mistrust between this collection of politicians and seasoned diplomats/embassy staff, who, on the other hand, feel they are more competent.

Add to the mix, the staffing of sons and daughters and relatives of the politically connected— in appointment and posting of lower rank Foreign Service officers to the embassies, and the perennial inadequate funding that has constipated work plans.

While employment of non-career diplomats as ambassadors is a widespread practice globally, many inside the Ministry of Foreign Affairs concur of the dire need for soul searching.

Analysis of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ records indicates that the ministry spends more on staff on contracts than general staff. For this financial year quarter one—July to September—the ministry is spending Shs752m on salaries of general staff and Shs824m on contract staff.

Ambassador Farid Kaliisa, who has been snubbed by DRC for three years.

The maintenance of many retired, albeit senior staff, on contracts, add to the cocktail of nepotism and cronyism means there is hardly any room for promotion of both career staff and lower rank Foreign Service officers. This has lowered morale of many career officers, some of whom have gone for 15 years without promotion.

Crippled service

Meanwhile, some of the country’s key diplomatic outposts remain vacant, among others, next door in Nairobi, one of Uganda’s biggest trading partner, Iran, and technically Kinshasa, where the DR Congo President Felix Tshisekedi has for three years snubbed Uganda’s Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Farid Kaliisa.

The snubbing of Ambassador Kaliisa to formally present his credentials, as is the customary practice, means he cannot work effectively in Kinshasa nor in Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo-Brazzaville, and Gabon.

This, as the ministry is saddled with reports of allegedly selling diplomatic notes to private individuals and the politically connected to fasten visa issuance by particularly the United States and European Union countries in Kampala. Some officials are also cited in the alleged sale of the country’s diplomatic passports anywhere between $10,000 and $20,000.

Particularly, the constant power struggles and fights have fractured work relations among staff at several missions, even where specific cases are unknown. In Brussels, Belgium, the embassy is in debt of Euros 170,000 (Shs698m) due to financial impropriety and embassy staff are routinely bickering over the meagre resources. The proposed construction project for the ambassador’s residence along Plot 35, clos de Lauriers, has further left the embassy staff divided over how and who cashes in. Across the Atlantic in Washington DC, a key mission, where President Museveni in 2021 assigned greenhorn Robbie Kakonge, the embassy is one matchstick away from implosion.

In Ankara, Turkey; in Rome, Italy; in Paris, France; in London, United Kingdom; in Algiers, Algeria, there is trouble brewing at many Ugandan embassies abroad.

Mr Nkunyingi told Daily Monitor that the problem is the country’s lack of a codified foreign policy that guides on the conduct and transaction of diplomacy and appointment of ambassadors and Foreign Service officers. “So we don’t know what to expect of our embassies abroad and they also seem not to know. In the absence of a policy framework it means there are inadequate checks and balances,” he added.

During the last decade, the Ministry has prioritised economic and commercial diplomacy (ECD), with each of the country’s 38 diplomatic missions—embassies and consulates—given key performance indicators to meet, but the failure to match the same with funding has rendered implementation problematic.

ECD relates to the embassies attracting foreign direct investment, and trade and tourism from all over the world as part of the implementation of the National Development Plan, the blueprint to drive Uganda into a middle-class income country, now in its third phase.

In fact, Uganda’s missions abroad serve three main purposes; economic/commercial, consular services and political cooperation. Some serve only one, two or all the three, owing to their mission charters, location, size, and budgets. Inexplicably, for this financial year, the ministry has prioritised 12 missions for funding in economic and commercial diplomacy, targeting particularly agro-industrialisation, tourism, mineral development, and science and technology. The selected missions are, London, New Dehli, Kuala Lumpur, Washington, Beijing, Paris, Abu Dhabi, Ankara, Algiers, Doha, Guangzhou, and Mombasa.

The ministry’s Permanent Secretary, Mr Vincent Bagiire, on June 24 wrote to the heads of the 12 missions, urging them to, among others, submit a clearly aligned work plan, identify key outputs, and submit a comprehensive work plan mapping Uganda’s exports in those countries.

“The success of the ECD strategy will require our collective efforts to align your Mission’s strategic objectives with the ministry’s framework and clarity in reporting measurable results,” PS Bagiire wrote.

The irony though is Uganda’s trade with some of the listed countries is currently dismal.

Diplomacy is primarily about rule-following and protocol enforcement. In a rapidly changing geo-politicised world, many countries are appointing their best and finest for the coveted ambassadorial positions to navigate, outmaneuver, and outsmart competition. By many accounts, Uganda is doing the reverse and as such, reaping what it sows.