Prime

Kabaka Muteesa flees palace to a tough life in exile

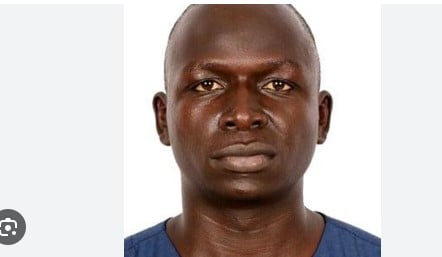

Kabaka Edward Muteesa II (C) receives the Queen of England (2ndL) in the 1950s. The British royal is accused of not giving support to Mutesa while he was in exile in London. MONITOR PHOTOS

In the third part of the series, Saturday Monitor’s Faustin Mugabe traces Muteesa’s flight from a life of royalty - following an attack on the Lubiri - to a penniless life in the United Kingdom.

On May 24, 1966, Kabaka Edward Muteesa II, a decorated captain in the British Grenadier Guards, fled his palace to exile and never returned alive.

A company (100 soldiers) of the Special Forces from the Uganda army had, in a surprise attack, penetrated and destroyed the palace defence under the cover of dawn.

The royal guards and everyone else in the Lubiri were overwhelmed by the enemy’s heavy weaponry – and simply surrendered only to be butchered in cold blood.

Kabaka Muteesa and his two most trusted military officers George Mallo and Joahash Katende managed to flee to Britain.

Later, Katende told the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into the violation of Human Rights in Uganda between 1964 to 1988, that the royal guards were poorly equipped. Only 68 were armed with a nine ammunition rifle each, on the fateful day.

A few options were available for the Kabaka after he fled from the palace. One of them was him ‘disappearing’ amongst his subjects in order to see another day.

The Kiganda saying that Kabaka Woligwa Wendigwa - translated as ‘I will die with my king’ - could have been the rallying point for Kabaka’s subjects.

However, if Kabaka Muteesa had put up a fight, would he have defeated Obote’s regime militarily and perhaps ended the war politically?

The second option, going to exile was not an easy one but the odds were heavily staked against the Kabaka. He had been overwhelmed at the battlefront and he could not hide among his people for long to wage a guerrilla war against premier Milton Obote’s government.

Other options

The other question that could be asked in retrospect is, if Kabaka Muteesa had been captured, would Obote have had him killed? Unlikely! Jailed him? Probably.

But, what would be the ramifications of the Kabaka ‘residing’ at Luzira prison? Muteesa in jail at the centre of his kingdom would have caused huge local and foreign sympathy. Besides, daily rumour and propaganda about his incarceration would have undoubtedly fuelled enrage in his subjects to act decisively and possibly change the political equation altogether.

Thus it could be said that Muteesa’s pathological fear of Obote that caused him to ‘retreat’ so far away from his enemy, partly demoralised his subjects, and today, history reads otherwise.

Anyhow, exile has never been an easy option. A story is told of how, former president Obote was bundled into a get-away car against his wish to re-run into exile hours to the 1985 coup.

It is alleged that in a drunken stupor, Obote had asserted: “I will die here. I didn’t come with a return ticket to exile”.

Janet Museveni too is said to have “protested” against a return to exile when Museveni asked her before the Luweero war started.

In her autobiography, My Life’s Journey, the First Lady writes of how she suggested that she would find a “haven” in deep Nkore village than return to exile. But after second thought, she reluctantly returned to exile.

Unlike in 1953, it is not recorded how much Kabaka Muteesa attempted to fight off the thought of the second exile.

On May 24, 1966, Kabaka Muteesa, was forced into another exile by Obote. The first was on November 30, 1953 when Governor Andrew Cohen on orders of the Queen, exiled the king to Britain.

Unlike in 1953, when the British government ‘hosted’ him, this time, the Queen’s government had reluctantly allowed him in her kingdom. In other words, Muteesa was ‘unwanted’ in Britain.

In his book about Muteesa’s second exile, The Bitter Bread of Exile, Abdul Kasozi reaffirms this when he wrote: “Sir Edward was admitted into the UK as a commonwealth citizen on the undertaking of his friends in the country who guaranteed to support him.” No wonder the Queen and her government ignored the plight of Muteesa from the day he was ousted till he breathed his last.

The Kabaka had previously collided with the Queen particularly in 1953, and 1961 when Buganda wanted to secede from Uganda. The two had not met to diplomatically reconcile.

Also, Britain feared to rock her diplomatic relations with Uganda. The question of the home country to the Asians (Indians) with British passport residing in Uganda had earlier simmered in 1963. Britain, just like Uganda, never wanted them. Thus, Britain feared to accord Kabaka Muteesa a better life against Obote’s wish.

On his first day in Britain, Kabaka Muteesa slept in a pub. Years ago, I had wanted to write this story, but my previous editors shied away from it. I had seen documents which the editors of Uganda Argus exchanged from London to ascertain the fact. Indeed, on August 15, 1967, quoting sources in Britain, the People newspaper published the story that Muteesa was staying in a pub in London.

Night in a pub

Kasozi also reaffirms this in his book. “On the first day of his second exile in UK, Sir Edward stayed in a pub in Surrey provided by a friend from the Cambridge days,” Kasozi wrote, attributing his source to the Times newspaper of August 11, 1967.

Kabaka Muteesa arrived in Britain without a penny on him and without a penny in his pocket, he died. Everything he had was provided by friends and well-wishers including the house in which he died.

Soon, news of a pauper life the Kabaka lived in London, reached his subjects back home.

However, every attempt to send him money was either foiled by the government, or swindled between Buganda and Britain. Some of those who were arrested by security for collecting or keeping money meant for Muteesa are still alive and ‘supporting’ Buganda as before.

When the Uganda Argus of June 23, 1967 lifted a story from the Daily Telegraph indicating that Muteesa was broke, a Muganda minister in Obote’s governments while in Bugerere warned CP supporters who wanted Muteesa to return and had been collecting money, to send the cash to him in exile.

The Uganda Argus had written: ‘Sir Edward Muteesa, the former Kabaka who left a private fortune behind when he fled to Britain last year said last night that he had no money of his own. Muteesa said: ‘My friends have made it possible for me to exist financially’.”

Every attempt by British friends to secure a job for Muteesa met a blunt excuse from the Queen or her government.

If Queen Elizabeth II wanted to help Kabaka Muteesa live a normal life in London, she would have done it for she had, in 1963, financially-aided the former Sultan of Zanzibar to settle in Britain after he was ousted in a coup led by self-styled Ugandan Field Marshal John Okello.

By avoiding meeting Muteesa, Queen Elisabeth II and his family members only proved the Kiganda saying that: Bagala alina - loosely translated as “wealth/prosperity attracts friendship” or, more directly, “they love he who has”.

Previously, Kabaka Muteesa had met the Queen. The Duke of Kent and members of the British royal family visited Muteesa on October 8, 1962 at his palace in Mengo. Then, the Queen needed the Kabaka politically to bind Uganda’s independence – and there he was for her.

However, when Kabaka Muteesa needed the Queen and her family most, they shunned him.

The series continues in Sunday Monitor tomorrow.