Sudan marks two years after Bashir expulsion

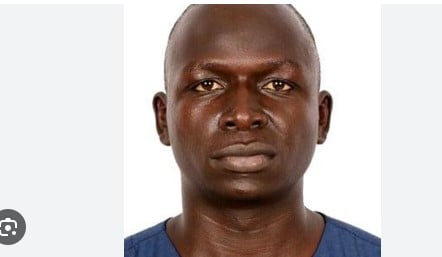

Former Sudanese president Omar Al-Bashir. PHOTO/FILE

What you need to know:

- The Transitional Sovereign Council is chaired by the military but it is supposed to change hands to a civilian rule this August.

As the Sudanese marked two years since the ouster of a man who held the country’s facilities for 30 years, there has been no consensus on what his departure brought.

Some cite the new stability and the return to the international arena, after years of isolation under sanctions from the US. Washington has since dropped those sanctions, allowing Khartoum to draw benefits from international trade and credit facilities.

It may take at least a year though, for those benefits to arrive in Khartoum and the general consensus is that the glass is half full and the victory is incomplete.

Bashir rode waves and waves of civil unrest, usually by crashing the dissent and using militia in the villages to fight his proxy wars.

That earned him an indictment at the International Criminal Court where he has yet to stand trial. In April 2019, his own military tired with his mode of leadership, and shifted camp with the protesting civilians.

Critics have described the military as saving itself, however, by the time it took over from Bashir and formed a transitional council. In August 2019, the council accommodated civilian representatives, including Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok.

Hamdok was the choice of the Sudanese Professionals Association, which led protests that ended Bashir’s rule on April 11, 2019.

1985 revolution

The month of April was not a coincidence. The Sudanese remember Jaafar Nimeiry, who was in April 1985 removed from power after 16 years. The military deposed him, after siding with civilians in rejecting his rule. That has since been known locally as the 1985 Revolution. Four years later, Bashir would take power from an elected government in a coup.

Sudan’s deposed military ruler Omar al-Bashir (right) stands in a defendant’s cage during the opening of his corruption trial in Khartoum on August 19, 2019. PHOTO/AFP

In Khartoum today, locals say there is better air of freedoms and other liberties. Sudanese rights activist Al-Sadiq Ibrahim argues the revolution was motivated mostly by the crash of the dissent and that events leading to the ouster of Bashir were aimed at alleviating the suffocation imposed by Bashir’s regime.

“The 2019 revolution achieved a change in leadership, a transitional stage from a totalitarian period marked by violations of civil rights to one marked by freedom, peace, justice and people’s choice,” he told the Sunday Nation last week.

Ibrahim argued that many Sudanese had high hopes for a more peaceful country. What has been achieved, however, is a reduction of the clampdown on civilians and a change in criminal procedures to reduce incidents of political prisoners.

“There is a trend of legal reforms, but the ordinary people in the street do not feel, yet, it due to the political complexities represented by the formation of the authority itself,” he said, referring to the transitional government which is to last for three years from 2019, after which elections should be held.

Bashir himself has since been jailed for two years for corruption and faces trial for a number of crimes, including a coup masterminded on June 30, 1989, killing demonstrators and opponents. A special team was also appointed to investigate his role in killings of protesters who pushed him out.

Big economic problems

Under the transitional period, the government is to address issues of people jailed for political views, facilitate access to justice, by making legal and administrative reforms of state agencies to ensure professionalism. Those agencies are also supposed to gradually accommodate former armed groups who have recently signed a peace deal with the transitional government.

“There is no clear discourse from the authority due to the delay in forming the parliament and the commissions, but the slowdown is governed by the balance of forces within the authority,” Ibrahim sqie, referring to the components of the transitional government which has civilian and military representatives.

The Transitional Sovereign Council is currently chaired by the military but it is supposed to change hands to a civilian air this August, part of an arrangement made to balance power between the two sides.

Abu Al-Qasim Ibrahim, an economist in Khartoum, told the Sunday Nation that the revolution has yet to implement crucial demands of protesters, including the economic issues.

“They haven’t touched the economic problems. Instead, they are under constant pressure from the IMF and the World Bank to tighten policies, which will make the life of the ordinary people harder.”

Sudanese Political analyst Yasser Al-Awad believes “there are goals that have been achieved, which will encourage the government to remain on course”.

He cites the return to the international community by lifting the US sanctions and the country’s removal from the list of those sponsoring terrorism, and the ensuing resumption of cooperation with international financial institutions, especially the World Bank.”

Questions have been raised regarding the cohesion and unity of the revolutionary forces in Sudan, more than a year after cracks emerged as the government disbanded certain units that had been associated with torture and disappearance of political activists.