Prime

How Anglican money helped the British colonise Uganda

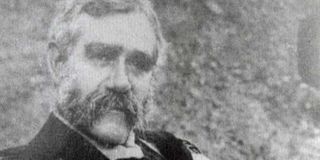

Bishop Alfred Tucker. He was the first Anglican Bishop of the Diocese of Uganda (1879-1911) and founder of Bishop Tucker Theological College, Mukono, in 1898. Courtesy Photo

The role of the Anglican and Catholic missionaries in the break-up of Buganda Kingdom has already been seen with their role in the ouster of Kabaka Mwanga and his reinstatement as a puppet.

This weakening of the Kabaka and his kingdom, led to the emergence of new power centres among the rival chiefs, especially Katikkiro Apolo Kaggwa, which would play a key role in the colonisation of Uganda.

However, the Christian missionaries played more than an indirect role in the political configurations that emerged in Buganda in 1888 and beyond. Theirs was the hand that rocked the cradle of Buganda’s civilisation and hundreds of years of independence.

As previously reported, the rivalry between the Anglican Alexander Murdoch Mackay and Catholic Father Siméon Lourdel had trickled down to their converts who not only identified themselves by their religious denominations but by the two countries, England and France, from which the missionaries came.

Catholics, Protestants drift apart

Despite uniting to beat off the Muslims and their puppet king, Kalema, the two factions quickly drifted apart, even after the death in the first half of 1890 of both Mackay and Lourdel, and continued to try and seek political advantage over the other.

By 1890 when Lugard forced Mwanga to sign the agreement putting himself under the authority of the IBEAC, the political landscape lay as follows: The Catholics had more converts, more white men in the country, probably more guns and enjoyed the support of Mwanga who had converted to the faith but had not been baptised. The Catholics also had two royal ‘hostages’ of whom more shall be heard of soon.

The Protestants, on the other hand, had the increasingly powerful Katikkiro as well as Lugard and his forces. Although he was under instructions not to favour one camp over the other, the Anglicans believed that Lugard, being English and Protestant, would represent their interests.

Lugard’s diaries show how he bent over backwards to try and keep the two European groups from each other’s throats, despite the Protestants being the weaker side at the time. The Catholics accused him of partisanship every time he settled a dispute in favour of the Protestants, who accused him of betrayal every time he did not.

It was amidst such a delicate state of affairs, and during almost weekly threats of war only calmed down by Lugard and his men that IBEAC director George Mackenzie wrote to Lugard in 1891 informing him that the cash-strapped company could no longer afford to stay in Buganda.

On August 10, 1891, McDermott, the secretary of the IBEAC, sent word to Lugard ordering him to leave Uganda and return to the coast. Lugard, who received the letter in December 1891 on his return from a military expedition to western Uganda, was, if possible, to try and renew the December 26, 1890 agreement with Mwanga for another two years or in perpetuity in case the IBEAC was able to return to Buganda.

He was also to leave one white man to act as a Resident but Lugard, aware that only his forces kept the Protestants and the Catholics at bay, despaired privately in his diaries.

“I am authorised to leave a Resident in Uganda, if I can find a volunteer,” Lugard wrote. “A volunteer for what? To stay in Uganda without position, authority, guard for personal safety — with no power to face anarchy, etc. Would you find a volunteer to go and hang himself? — It is pure madness. The task is hard enough even now, as long as these armed factions are evenly balanced and forever at each other’s throats; but with no force at all!”

As it turned out, Bishop Alfred Robert Tucker, who had arrived the day after the Lugard-Mwanga agreement, but who had since returned to England, then stepped in to tip the hand of fate and the history of our country.

Raising the money

Having been approached by Sir William Mackinnon of the IBEAC to help raise £15,000 to keep the company in Buganda (the former and his colleagues were willing to find £25,000), Bishop Tucker raised the money in just two weeks, including £8,000 in just one night.

On January 7, 1892, just as Lugard was sending a team of 30 to the coast, including Capt. William who was to travel to England and get some public support for the continuation of the company’s presence, he received a letter informing him that IBEAC could stay in Buganda for another year, up to December 31, 1892.

Lugard’s departure and that of his forces would have changed the history of Buganda and Uganda in many ways. In all likelihood it would have led to a civil war between the religious groups or the withdraw of the Anglicans, which could have left the Catholics to fight off the Muslims and lead either to a French colony, or to a German colony – the Germans were across the lake in Tanganyika and still interested.

Cecil Rhodes, the British/South African empire builder who would go on to colonise present-day Zambia and Zimbabwe, had also offered IBEAC £25,000 a year to manage Buganda and the nearby territories. Could this have led to a colony that extended south to those countries if IBEAC had accepted the offer?

As it were, Bishop Tucker’s intervention had bought the company a year’s grace. Working closely with Lugard, the Church Missionary Society then went on a public relations offensive in England with the sole aim of turning Uganda and Buganda into a British colony.

It was a campaign in which facts and the truth would be cast aside in order to convince the British public and politicians that colonising Uganda was not just a good thing to do but a moral obligation as well.

The missionaries had effectively jumped whatever was left of the line between Church and state. In July 1892, an election in Britain would aid the Church Missionary Society in this endeavour but thousands of miles away, as the rains fell in Buganda in January 1892, the drums of war were sounding in the distance.

Lugard’s take on missionaries

“How far a similar policy of creating a political influence in favour of British rule had been promoted by the Protestant missionaries, I have no accurate means of knowing. Doubtless they were little behind the Fathers in their desires to secure in Uganda the supremacy of the nation to which they belonged. For General Gordon, speaking of the Uganda mission, says, that, “as it is composed, it is more secular than spiritual” and accordingly writes to indicate the political attitude the mission should take. Mackay’s letters prove him to have been a most zealous promoter of British supremacy; and Mr Gordon’s action upon and subsequent to Mr Jackson’s arrival indicates that the missionaries apparently considered that they were the representatives of British interests.” Frederick Lugard in The Rise of our East African Empire.

Continues tomorrow.