Prime

Post-independence Disagreements: How Mutesa contributed to the 1966 Lubiri attack

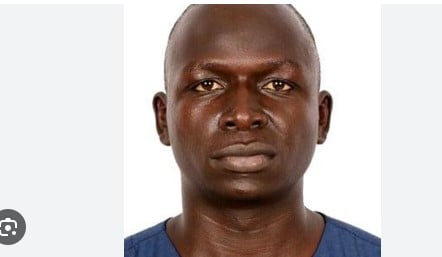

Uganda Army soldiers after attacking Mengo in 1966. Kabaka Mutesa was forced to flee the palace COURTESY PHOTO

What you need to know:

It is truth well documented that Kabaka Mutesa ordered for a consignment of guns from the UK in 1965. After Obote got wind of the same - plus the Kabaka’s order to vacate Buganda - the PM consequently ordered the attack on Lubiri.

I would like to respond to Peter Mulira’s article, “The history of Buganda did not contribute to the 1966 Crisis,” published in Sunday Monitor of June 17. Peter Mulira is normally an intellectually honest man but this time he either has lacked the facts or has tried to manipulate them. In the article he seeks to deny the role Mengo or Kabaka Mutesa himself played in the 1966. I would like to argue to the contrary; but before I do that I would like to refute a few things Mulira said.

He writes: “As 1966 began, the Ibingira camp was on top of things resulting in a decision to have Obote arrested by the head of the army, Brig. Shaban Opolot.” This statement is not only false but reminds me of what an article, “The rise and fall of Grace Ibingira,” published in December 1966 tells of Obote:

“In political tactics, Dr Obote’s pragmatic idealism takes the form of cautious waiting and quick advance at time of his own choosing. He allows his opponents to muster strength, to let their aims become known, to build up internal factions within their own coalitions, to overextend themselves in grasping for power just out of reach.

Meanwhile, he consolidates strengths and removes minor weakness. At times he gives the impression of losing control over situations. Then as rumour begins to herald his coming defeat, he moves rapidly and decisively; his immediate objective attained and the whole opposition thrown into disarray, he gains speedy adoption of major changes whose mere proposal could have cost him his office before the crisis.”

Trapping the Ibingiras

Totally in accord with this description of Obote, and as though they were acting according to a script written by Obote himself, immediately Obote left for the northern tour, the Ibingiras walked right into his trap. Just as Mulira says, they thought they were “on top of things”.

At a UPC Parliamentary Group meeting on January 31, 1966 it had been agreed that when Daudi Ochieng tables his motion about the Gold Allegations against Idi Amin on February 4, 1966, it would be rejected by UPC. Obote had told the Parliamentary Group that he would be living for a tour of northern Uganda soon after the meeting and would not be around for the debate and vote on the Ochieng motion.

In contravention of this, some 15 minutes before Parliament assembled on the mentioned date, the cabinet was hastily assembled and the earlier decision of the Parliamentary Group reversed. All UPCs were then required to vote for the motion.

The cabinet which met on February 4 and decided to reverse the position of the UPC Parliamentary group was dominated by the Ibingira faction which included the ministers who were later detained. Also half of the members of the cabinet were absent. Curiously the three members of the cabinet whom Ochieng’s allegations were targeting were not present. And those absent included Onama, the Minister of Defence, who should have been there by virtue of the fact that the Ochieng allegation concerned his office.

We should also point out that the cabinet meeting was held when it was clear there would not be time for Obote to be contacted nor, even if he could be contacted, for him to come in time for the debate and vote on the motion.

Another point to be noted is that the UPC Members of Parliament only learnt of the changes from the Floor. This created a lot of confusion among them.

Mulira also wrote: “Realising the dire situation he was in, Obote left the capital to go to the north to inspect government programmes, but in reality, he wanted to escape to Congo if the arrest was attempted. After Brig. Opolot had left the capital with his troops to arrest Obote, the Ibingira group held an audience with the President, Sir Edward Mutesa, to brief him about what was happening.”

This is also false. Contrary to what Mulira is suggesting here, Obote’s tour of northern Uganda had been planned well ahead of time. The previous November he had promised but not fixed a date to tour the northern region in January or February of 1966. The date for the tour was fixed in January, and he left for the tour on February 1, 1966.

In place of what Mulira is saying, a cynic would rather say Obote knew they were planning against him so he deliberately left the capital so that the plotters would get the false confidence that they were in control. This cynical conspiracy theory seems to be born out by the events that actually took place.

Professor Mutibwa seems to accept this conspiracy theory. He wrote: “But they all forgot one or two things namely Obote’s sagacity and the General Service Unit’s efficiency. Although he was away, Obote knew perfectly well what was going on and he had the capacity to handle it. For how could he have remained ignorant of such events when his cousin, Akena Adoko, was in charge of the efficient intelligence network of General Service Unit. That is why only fools could believe his side of the story where he later told Parliament that he was not aware of the plots that his enemies planned all along behind him.”

Mulira further wrote: “As soon as Obote received news that there was change of heart about his arrest, he returned to Kampala on February 17, 1966 and on February 22, 1966 surprised many by convening a Cabinet meeting where he got five ministers in Ibingira’s group and Opolot arrested.”

Obote returned to Kampala on his own volition on February 12 (please note: not 17th as Mulira says) and, in his own words, realised “the situation was very serious.” He immediately ordered the troops back to their barracks, and sought to discuss the situation with Mutesa, the then President.

He also convened an emergency meeting of the Cabinet on February 14 at which he called on the Ministers who had lost confidence in him, and had believed in the allegations by Daudi Ochieng to resign. None resigned.

Obote off to Nairobi

Three days later Obote left for official duties in Nairobi, returning on February 19 when he learned of a circular by Brigadier Opolot to all army units, directing them to go for field exercises. In this circular, “Opolot actually stated that because the situation had been normal throughout February 1966, and because for some period of months the army had not done field exercises, February 1966 was the most suitable.”

Obote found these observations curious to say the least, ordered cancellation of the exercises and later took what he termed “drastic action”. The drastic action was the detention of the five ministers involved in the plot to overthrow the government.

Mulira also wrote: “After Brig. Opolot had left the capital with his troops to arrest Obote, the Ibingira group held an audience with the President, Sir Edward Mutesa, to brief him about what was happening. Mutesa was against the arrest and advised on sticking to Ochieng’s motion in the interest of the country’s stability. Opolot was ordered to return to the capital and this was Obote’s finest hour.”

While this is false, it is curious that Mulira, a lawyer can write this without realising that he is placing Mutesa in a situation where he is aware of treason being committed and in stead of turning in those consulting him, he is instead advising them on the better course of action to overthrow the government. This act by Mutesa is itself treasonable.

That said, the truth is a contingent of well-armed soldiers was on February 7 sent to arrest Obote in northern Uganda. Unfortunately for the mission, a secretary at the army headquarters heard about the mission and told her brother who immediately went and informed Obote. When the contingent arrived at where Obote was they found him under heavy guard. The contingent was disarmed.

The only thing they ended up doing was to deliver their cover message which was that Opolot wanted Obote to go back to Kampala and call the defence Council to settle the case of Amin wanting to kill Opolot. In response to this Obote told them to tell Opolot that a Defence Council meeting to handle the matter would be held in Arua. Opolot never responded to this proposal.

On February 8, the army headquarters, presumably under the direction of Opolot, instructed Jinja to send recruits to Kampala under the rationalisation that they were going to protect the capital. Specific troops had been recruited and prepared for this mission. However, whether by design or default Brig. Okoya who was in charge of the Jinja military outfit sent the wrong troops.

This matter of wrong troops was reported to Mutesa that same day: “The Uganda army is bad; it supports Obote. If you want to bring changes, you may need to try other armies.”

Following this advice, Mutesa the following day (February 9) called two people: the British High Commissioner and the Chief Justice, Sir Udo Udoma (a Nigerian). He requested the British High Commissioner for military aid and the Chief Justice for advice on how to fire the Prime Minister, Apolo Milton Obote.

As ceremonial president, Mutesa had no powers to do these things. About the approach to the British, Professor T.V. Sathyamurthy, the author of the encyclopedic book, “The Political development in Uganda,” had this observation to make: “But the Kabaka’s approach to foreign emissaries was born more out of foolishness than craft. For, it was the strongest card in Obote’s possession when it came to delivering the final blow.”

In an attempt to vitiate the seriousness of this request for foreign troops, on March 4, 1966, the Private Secretary to Mutesa issued a statement in which he contended that the request was precautionary. To this Obote responded:

“I have noted that it is now being explained that these were precautionary requests. The fact remains that there was no provision whatsoever in the Constitution for the President to make such requests. An attempt was made to justify this serious matter by allegations made in Parliament on February 4 that there were troops being trained in secret with a view to overthrow the Constitution.

Mutesa places order for arms

In addition to this, the reader should also remember that in December 1965, Mutesa placed orders for heavy weapons with a Kampala firm, Gaeily and Roberts. On this Obote was later to write in his pamphlet, “Myths and Realities -- A Letter to a London Friend,”:

“We have letters from a British firm which show that the firm was not happy with the orders on the grounds that the weapons ordered were too heavy for an individual and that the firm had always dealt with governments only. One of the letters from the Kampala firm states that President Mutesa had placed the orders on behalf of the Uganda Army and that, although the Kabaka’s Government was to pay for the arms, that only meant that the President, in his capacity as the Kabaka, was to have the first trial of arms before handing them over to the army.”

When a police officer went on routine briefing to Mutesa on February 21, Mutesa asked him whether he knew that something was to happen on February 22. When the police officer answered that he didn’t know, Mutesa told him not to worry because it was one of those Kampala rumours. However, immediately after the visit, the police officer briefed Obote about the mysterious question. To Obote this was further confirmation that the coup was to take place on that date.

Two days after the detention of the five ministers, Obote called a press conference on February 24 at about 7.00 pm and announced he had suspended the Constitution of Uganda. “Recently attempts were made to overthrow my government,” he explained, “by use of foreign troops, by persons who hold high posts by virtue of the Constitution. These requests were illegal but continue to be made. To safeguard our sovereignty we must take counter measures: suspending the Constitution and hence the posts of President and Vice President.

Mutesa, as Kabaka of Buganda, issued an ultimatum for the Central Government to vacate the soil of Buganda before May 30, 1966. Although he later said this was a mere bargaining chip, both his friends and foes interpreted the ultimatum to mean de facto secession of Buganda from the rest of Uganda.

As a response to the ultimatum, Obote, as head of the Government of Uganda, declared a state of emergency throughout Uganda. Subsequently, on June 1, in a move which treated the ultimatum as an act of rebellion, Obote ordered units of the Uganda Army to march on the Kabaka’s palace at Mengo. It had been reported that the Kabaka had amassed arms in the palace in readiness for war, and the troops were to search the palace.

As the troops approached the palace, they were fired at. A battle ensued. Professor Mutibwa tells us the battle was stiff: “Although Mutesa, assisted by his lieutenants equipped with Lee-Enfieled riffles put up a stiff resistance and Amin forces were obliged to call in large contingent of reinforcements, it was not to be expected that Mengo could hold out for long against the Uganda army.”

Eventually, after 12 hours of fierce fighting, the Uganda Army established control. The Kabaka had escaped from the palace.