Prime

Easy medals give African boxers false confidence

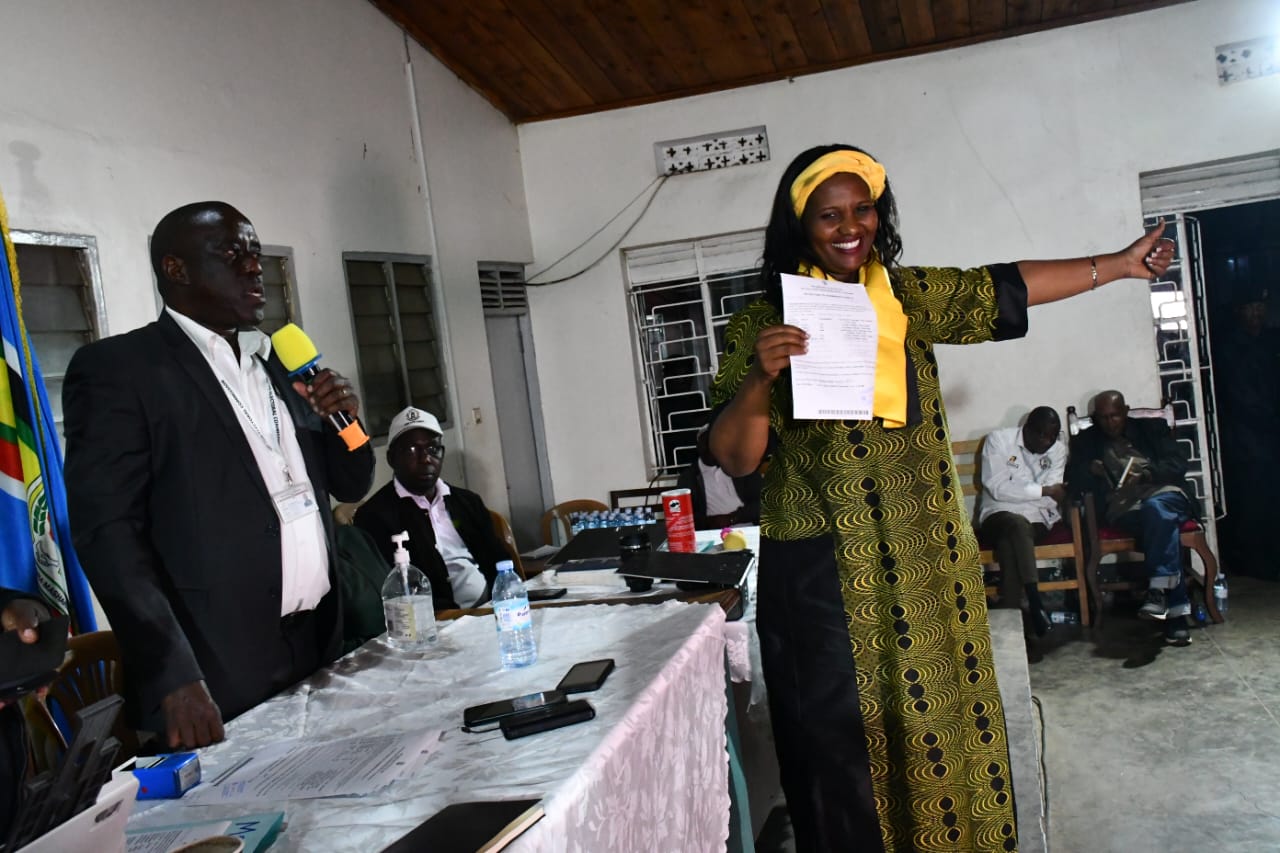

Boxer Yusuf Nkobeza. PHOTOS/JOHN BATANUDDE

What you need to know:

But how could an international record-breaker fade that fast into oblivion? Simple: she was just a lucky bronze medalist.

When Hellen Baleke got a bye to the semifinals of the 2019 African Boxing Confederations Championships without breaking sweat, she instantly made news as the first Ugandan woman to win a medal in an international boxing event.

But the boxer quickly faded into oblivion like a thin vapory cloud, even before the tournament ended after Morocco’s Mardi Khadija stopped her in the first round of the middleweight semifinal bout.

“Hellen was no match for that girl,” one of the boxers who witnessed the fight in Rabat told us.

Since then, Baleke, a ghetto hustler who was also outclassed by world and Olympic champion Claressa Shields at the 2014 World Women’s Boxing Championship in Jeju Korea, retreated to Katanga slums, where she resorted to helping disadvantaged youths via income generating projects.

But how could an international record-breaker fade that fast into oblivion? Simple: she was just a lucky bronze medalist.

She is not alone. Teddy Nakimuli, also got bronze at the 2022 Commonwealth Games in Birmingham, the first Ugandan female boxer to achieve that, more over on her international debut.

Barely two years later, Nakimuli is almost forgotten. Why? When she got the chance to fight for glory, the girl from University of Pain flopped against Northern Ireland’s Carly McNaul.

A year later, Nakimuli’s clubmate flyweight Grace Nankinga, light welterweight Erina Namutebi and superheavyweight Solomon Geko got byes to the semifinals at the 2023 African Championship in Yaounde, Cameroon. Only Namutebi reached the finals. Nankinga and Geko lost the semis but each returned home with a bronze medal and assured $5000 (Shs18m) in prize money.

Weeks later, Nankinga lost her first bout at the African Olympic Qualifiers in Dakar, Senegal, where only finalists would get the ticket to the Paris 2024 Olympics.

It’s a continental problem

Not that only women are guilty of scooping medals by luck, and failing at the next hurdle. Yusuf Nkobeza, a bronze medalist at the 2022 African Championship in Maputo, Mozambique, recently flopped at the 1st World Olympic Boxing Qualifier in Busto, Arsizio, Italy last month. He needed to reach the semis to get the coveted ticket to Paris. He lost in the Round of 64 to Andrei Aradoaie. Not that the Romanian was exceptional. He also lost to Turkish Kaan Aykutsun in the next bout. But Nkobeza was no match for him.

Boxer Yusuf Nkobeza. PHOTOS/JOHN BATANUDDE

Ironically, Joshua Tukamuhebwa, who has never won an international medal, usually wins the most number of bouts at big events. In Italy, he won two, including one by stoppage. By losing in the quarterfinals, the Bombers captain was one win away from landing the Olympic ticket.

But none of the 68 African boxers in Italy got the tickets to Paris. Surprisingly, even the Refugee Team qualified a boxer. But as it stands, only 18 Africans (seven men and 11 women, who excelled in Dakar) have qualified for the Games, with one last qualifying tournament due in Bangkok, Thailand next month.

At the 2023 IBA Men's World Boxing Championships, no African boxer reached the semifinals, even when 20 countries including USA, Netherlands, New Zealand, England, Scotland, Germany, among others, boycotted due to Russia’s entry. Something wrong is happening to African boxing, once a source of world contenders.

Is it a dearth of talent? Poor preps for tournaments due to inadequate funding or complete lack of exposure to spaces where their European, American and Asian opponents perfect their craft?

In some instances, it could be any of those factors could be at play singularly or in combination. But the low levels of competition at African tournaments should also not be ignored. At the ongoing Mandela African Boxing Cup in Durban, South Africa, for instance, 37 nations entered boxers. But the overall entries are far below the competition threshold. Some categories have only three competitors, with one already waiting for the final. Others have only two.

After the draw, three Ugandans are assured of medals, and a big chip off the $500,000 prize money. But such medals got on a silver platter are no less sources of false confidence to African boxers, who face the bitter truth outside the continent.

Uganda Boxing Federation (UBF) president Moses Muhangi thought of a quick fix.

"It is a serious issue because it has watered down the quality of boxing owing to limited entries, weak boxers winning medals due to few entries and lack of competitiveness in some weight classes. That's why we see most of our African champions struggle to make it in world championships,” Muhangi recently told Nenez Media.

He wants the International Boxing Association (IBA) to amend the rules to such that for a national federation to be admitted into an IBA competition, it must enter a minimum number of boxers. He suggested 13 men and 12 women per country.

Muhangi added that the lack of a minimum requirement for entries is also what gives African governments the leeway to dictate how many boxers will be funded for which tournament.

Need for more tournaments

Vicky Byarugaba, John ‘the Beast’ Mugabi, Charles Lubuulwa, among many others from Uganda’s golden era will easily cherish the exposure they got from regional and intercontinental championships throughout the calendar.

There was Urafiki—an annual friendly contest between Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania. Bingwa wa Mabingwa (Champion of Champions), also among the three East African countries, which has for years become a shadow of its competitive self.

There was the Africa Zone V, which included giants like Egypt among others. Fescaba—Federation of East, Central and Southern African Games, which pitted East Africans against Zambians, Zimbabweans, Ethiopians, Congolese, among others.

There was the King’s Cup in Thailand, where Africa’s best met Asia’s best every year. Most of those tournaments are defunct or lost steam.

The Feliks Stamm International Boxing Tournament, mostly in Poland, which brought Europeans, Africans, Asians in one ring.

Such tournaments bridged skill and psychological gaps between Africans and their international opponents. Such that when they met at the Olympics, say, the playfield was somehow level. Feliks Stamm still happens, but Africans no longer participate.