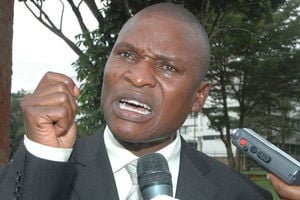

Then Presidential Press Secretary Tamale Mirundi speaks to journalists near the entrance to Parliament on January 11, 2010. PHOTO/ FILE

Joseph Tamale Mirundi, a veteran journalist and political commentator, who died on Tuesday after being taken ill at Kisubi Hospital, was the very embodiment of an enigma. The man, who told anyone who cared to listen that he was born anywhere between 1960 and 1969, was early this year wheeled into Kisubi Hospital in what many described “a worrying state”.

Many were quick to write his epitaph. When no confirmation of his death came through, an acquaintance of Tamale’s placed a call to his private number. To say that the phone conversation was awkward would be putting it mildly.

“Mirundi, is it true that you are dead?” the acquaintance asked.

“Yes, you are lucky you are speaking to a dead body,” came the response.

In many respects, Mirundi was the proverbial cat with nine lives. Pronounced dead, he would turn up clad in either ill-fitting suits or a yellow NRM shirt. The only constants were a yellow beret emblazoned with President Museveni’s face and an old rosary around his neck.

The man nicknamed Omukukuunavu or Muzzukulu wa Mirundi (Mirundi’s grandchild) was born in Rakai District. He won acclaim for a take-no-prisoner approach that saw him slice through socially sensitive subjects. No one was spared his criticism, including Buganda Kingdom where he was not just a subject but also once served.

The rosary around his neck also ought to not have fooled you as Mirundi pulled no punches when addressing the clergy. While he publicly expressed support for witchcraft; privately, he never tolerated wizardry.

Post-truth times

An opinion leader, Mirundi would often package his unverifiable allegations in a typical indistinct English accent and Luganda language to convince his audience. His media shows were rich in theatrics and humour, with a dose of profanity and drama. There was also a lot of misinformation and disinformation as Henry Lutaaya, an editor at The Sunrise, shares.

Mr Lutaaya had a run-in with Mirundi in 2014 that resulted in the latter showing off a pistol at a restaurant on Dewinton Street in Kampala. Mirundi had taken exception to a story The Sunrise wrote about him. When Mirundi was asked about the episode while on a television show, he told all and sundry that he had arrested the editor and the entire newsroom.

“I received very many phone calls from concerned persons who told me that Mirundi had arrested me and the entire newsroom. I immediately switched on the television and I watched him seriously explaining how he had bundled me up and put me in his car trunk, of course it was a lie,” Lutaaya remembers.

Journalist Felix Kyeyune, who worked with Mirundi at The Voice newspaper in the late 1990s, shares that it was always wise to fact-check Mirundi’s assertions.

“He could say something to suit a situation and he would sometimes amend it later,” Kyeyune notes.

Kyeyune, for one, remembers when Mirundi became a panelist at Kiriza Oba Gaana, a political show on the Buganda Kingdom-owned CBS FM. Mirundi would often choose not to criticise the kingdom. Once off the CBS FM airwaves, he would let loose when he appeared on another media outlet.

In his regular talk show on YouTube, Mirundi revealed that he was once cautioned by President Museveni on drunkenness. By his own admission, Mirundi said he lied to the President that he never used to take alcohol.

“The President asked why I had appeared drunk on TV and I told him my eyes appear red because I am allergic to studio lights,” he said with a straight face.

Loved and loathed

In his latter days, Mirundi’s appeal to social media audiences had grown. This came at the cost of his appearances in mainstream media. This was a deliberate choice by media managers and owners after the Uganda Communications Commission moved to isolate the man whose politically venomous critiques seemed to only spare President Museveni.

While appearing in the mainstream media, Mirundi coined derogatory nicknames for Mr Museveni’s son-in-law Odrek Rwabwogo, journalist Andrew Mwenda, minister Frank Tumwebaze, and others for allegedly aiding his exit from the State House.

Mirundi had previously served at the seat of power in Uganda, replacing John Nagenda as the President’s press secretary. Serving as a presidential adviser, Nagenda branded Mirundi “an idiot and a nobody” during a 2017 interview with this publication.

“This idiot and you can call him an idiot. The one who was press secretary. What is his name? How could Mirundi Tamale be the spokesman for anybody in this world and in the next world? It is impossible. The fellow doesn’t have a single strand of brain in his makeup and yet, maybe for years, he was the so-called spokesman,” Nagenda ranted.

In his last days, Mirundi often called out the ruling party, NRM and President Museveni for “using and dumping him”. He publicly regretted offering his loyalty to NRM amid praising it and acknowledging financial gains from Museveni.

Creepy death wish

Mirundi would often call out media outlets that carried stories that he never liked. In a number of media interviews, he asked his family never to allow government-owned media outlets to profit from his death by writing stories about his death.

The list of media outlets kept growing, depending on what would have annoyed him.

“When I die, the spokesperson of my family will immediately show up with a court injunction stopping some media outlets from writing about me,” Mirundi said.

Besides asking to be buried while standing, Mirundi further shared, in several interviews, that he wants his grave to have a glass cover so that he could see the outside world.

He repeatedly said upon death, a vigil should be held for three days at his home in Zana, two days in Kabalagala, two days at Kyengera, and two days at his village home in Matale-Kaliisizo.

Journalism career

Journalist Felix Kyeyune, who worked with Mirundi at The Voice newspaper in the late 1990s, shares that his journalism career began at Munno, a Catholic Church-owned newspaper. This was after working as a newspaper vendor at Ngabo newspaper in the 1990s.

Mirundi later started his own Luganda tabloid called Lipoota, which later collapsed. He became a business partner at The Voice newspaper, where he worked as the chief editor in 1998.

He was a pioneer panelist on Radio Simba’s political talk-shows Gasimbagane ne Bannamawulire and Olutindo before he became a nomad, hired and fired for his maverick approach to journalism.

It is understood that following the collapse of The Voice in November 2000, Mirundi attempted to negotiate his way into politics as a Member of Parliament but luck was never on his side.